Could a streetcar be the key to reviving downtown Seattle's arts and entertainment scene?

Downtown Seattle has the Seattle Art Museum, the Paramount, the symphony, along with other theaters and galleries. But it hasn’t been the center of Seattle’s arts scene for a long time.

Now, with downtown struggling economically, Mayor Bruce Harrell has been talking about a new arts and entertainment district downtown. He wants to put a streetcar right down the middle of it.

The city has even branded the proposed streetcar line as the “Culture Connector.” So, you can’t talk about the streetcar now without thinking about the arts.

This raises a question: What do streetcars have to do with art?

More than you’d think.

The idea is that the streetcar would link together various cultural experiences from the Center for Wooden Boats, north of downtown near Lake Union, down south to the Chinatown gate, before the line heads up to Capitol Hill.

It’s one example of Harrell’s long-term ideas that he feels could reenergize downtown over the course of many years. He's doing a bunch of short-term things too, like turning one block of Pike Street into a car-free, pedestrian zone. But the arts and entertainment district is an example of what he calls “Space Needle thinking.”

“This is our time to redefine the city,” Harrell said at his State of the City speech earlier this year. “We're talking about using the built structure to talk about where people will sing and give poetry and reclaim the arts and the culture, and making sure this is a vibrant place.”

We have not heard much more about this big idea of a downtown arts and entertainment district since this summer, when Harrell released images of what that district could look like on a website promoting the proposal.

RELATED: 'Game-changer' or commuter nightmare? One developer's pitch to pedestrianize Seattle's Third Avenue

Putting the streetcar line at the center of this arts renaissance is not just a gimmick. It turns out there’s a strong correlation between the presence of the arts downtown and transportation, whether it's streetcars or single occupancy vehicles.

Sponsored

It comes down to space. There's a limited amount of real estate available downtown, especially at the ground level; parking requires a lot of money and space to build. Those things make real estate more expensive, and that makes it harder for arts organizations to survive.

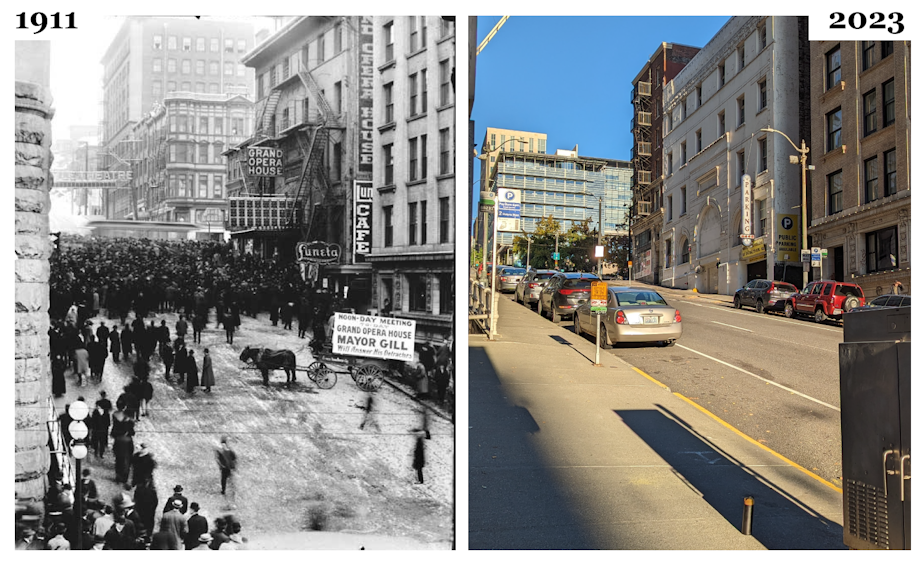

Streetcars, on the other hand, don’t require parking spaces at each stop. That makes more room for the arts. In the early 20th century, a lot of people got around Seattle by streetcar. During that time, there were dozens of theaters downtown — one within a short walk of every downtown home. The Grand Opera was one of the first.

When it was built, it was the first “respectable” theater north of the red-light district south of Yesler. The red-light district theaters offered vaudeville with a side of booze and prostitution. In contrast, the Grand offered performances like Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream."

Sponsored

The year the Grand Opera opened, 1900, was the same year the first automobile drove through Seattle. Twenty years later, after the Grand Opera was damaged in a fire, there were so many cars downtown that the owners of the property decided to turn the space into a parking garage. Thus, the Grand Opera became one of the first multi-story parking garages in Seattle.

Eugenia Woo is the preservation director at Historic Seattle. Earlier this summer, she visited the former Grand Opera and gazed up at its façade.

“What's amazing to me, if you look at historic photos of the exterior, what we're looking at today is pretty much what was designed and built in 1900, with some alterations. They used existing openings to put in the garage entrances,” Woo said.

Today, people entering the garage drive up what were formerly the front steps of the opera. The competition between the arts and parking is rarely as direct as it is in this case, but it's more common than you might think.

Sponsored

The Pantages Theater, for example, was replaced by a parking garage that was later torn down. The Metropolitan was torn down to make space for a vehicle drop-off area in front of what is today the Fairmont Olympic Hotel. Over the decades, many downtown theaters were demolished as cars increasingly took over.

Seattle’s initial streetcar network was dismantled in 1941, as cars started taking people to the suburbs. Fewer people wanted to live downtown — or at least fewer people with disposable income.

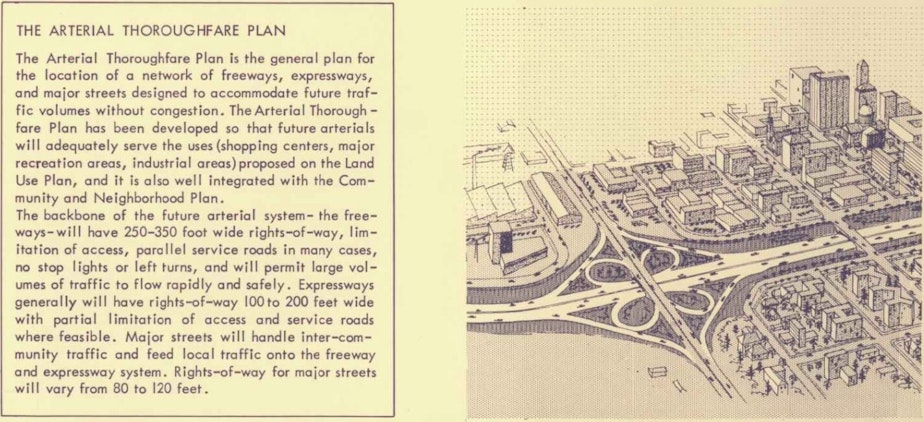

Planners developed a utilitarian vision of downtown as a machine for getting commuters in and out of the city.

Sponsored

“There was a plan to build a series of ring highways around Seattle,” said Knute Berger, a historian and editor at large for Crosscut. “The objective of that was to have a feeder road that could then feed people — commuters, suburban commuters, particularly. They were going to tear down most of Pioneer Square.”

Berger added that they were going to tear down Pike Place Market and replace part of it with a parking lot.

This focus on highways and vehicles with rubber tires led to a problem, he said.

“If you were going to turn downtown essentially into a workplace that could compete with the growing suburbs, and you were going to develop more retail shopping, more parking, more office blocks, where was the culture going to go?”

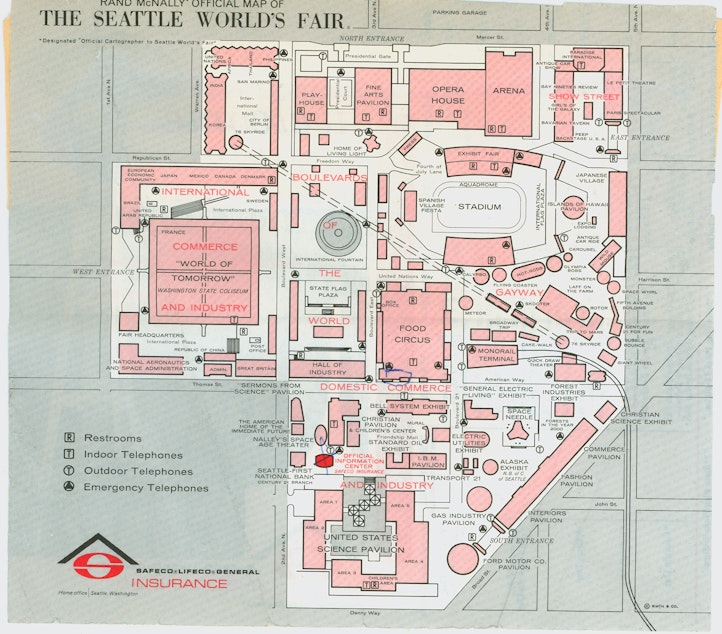

It was going to go in the Seattle Center, home of the Space Needle. The Seattle Center was being built to house the 1962 World’s Fair, also known as the Century 21 Exposition.

“It was meant to be one-stop shopping for the arts,” Berger said.

RELATED: SIFF acquires historic Seattle theater Cinerama

The Seattle Center is not downtown. It’s quite a bit north of downtown, a little too far for many people to walk, so the two are connected by the monorail. It’s home to a sports arena and multiple arts institutions, including the Seattle Repertory Theatre, the Pacific Northwest Ballet, and the Seattle Opera. The Seattle Art Museum also had a major gallery there. And while Seattle Center’s designers drew inspiration from the suburbs, its main difference from downtown is its park-like, car-free environment.

Sponsored

The moment the World’s Fair opened, downtown lost its title as the center of Seattle’s arts and entertainment scene.

But in the decades after that, arts and entertainment slowly made a comeback downtown. The main reason: A growing number of people found ways to rely less on their cars.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Seattle saw grassroots resistance to tearing buildings down to make way for parking. The Pike Place Market was saved in 1971 by voter initiative. Another grassroots movement saved several of the remaining downtown theaters, including The Moore, The Paramount, and the 5th Avenue. Those were eventually updated for modern performances.

Washington's Legislature made it easier to build condos in the early 1980s, according to Berger which led to an influx of young professionals and older residents who never gave up on downtown living in walkable neighborhoods like Belltown and Pioneer Square. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, these neighborhoods were full of galleries and performance spaces.

While real estate pressure from condo developments eventually made it hard for artists to afford being in those places, that same urban money drew the attention of arts institutions like the Seattle Art Museum and the Seattle Symphony, which relocated to the heart of downtown.

Many people who visited those arts institutions did not need cars, thanks to those new Belltown residences. Gerard Schwartz, conductor of the Seattle Symphony, walked to work from his Belltown condo, which had a great view and a grand piano, according to Berger. Philanthropists and developers Virginia and Bagley Wright lived across the street from the Seattle Art Museum, which they patronized generously.

The symphony and art museum moved downtown as part of a great public push to bring arts back. It wasn’t without risk: 1st Avenue was known more for peep shows and pawn shops when the Seattle Art Museum opened in 1990, but public subsidies sweetened the deal. As a result, the Seattle Art Museum is owned by the public (through a museum development authority), while Benaroya Hall, where the symphony plays, is owned by the city of Seattle.

Both institutions opened during the tenure of Mayor Norm Rice, who served from 1990 to 1998. He describes the beginning of his term as if the city were waking up from a fever dream in which the interests of cars were elevated above all else.

RELATED: Former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice and the origins of Seattle's growth strategy

“When we started out, the car was the bane of everybody's existence,” he said. “We were building things for cars. And if you do that, you need parking lots, you need big open places. That's a problem.”

The threat that cars and parking represented for the arts shouldn’t be overstated — there are other forces at play. People are attending live performances less today, compelling arts institutions to draw from a wider patron pool than they did during the streetcar days. Certainly, the Seattle Art Museum and the Seattle Symphony draw from a region-wide population, and many of their patrons rely on parking lots.

But understanding this history of how parking created competition with the arts for space downtown helps explain why the streetcar is the spine of Harrell’s proposed arts and entertainment district, along with greater residential density, which elected leaders recently allowed near Pike Place Market.

The streetcar, though, has hit some bumps in the road. According to the mayor’s office, support of the Culture Connector is mixed on the City Council. That’s led to a stoppage of funding for a study called the “delivery assessment” that will lay out when a streetcar through downtown can be built, and how much it will cost.

However, Seattle Department of Transportation staff are still pushing the study along in the background, and the mayor’s office says the report should be out by the end of the year.

Correction Note, November 3, 2023, 12:05pm: Corrected the year of the iniative that saved the Pike Place Market. It was 1971.