Cap-and-trade law tackles big polluters, fractures political alliances

A sweeping climate proposal from Gov. Jay Inslee has both fractured existing alliances and sparked new ones — among activists and oil refineries alike — on its way to becoming Washington state law.

The divisive bill, now awaiting Inslee’s signature after passing the state legislature, puts a cap on how much carbon dioxide the state’s biggest polluters can spew into the air and makes it more expensive for them to do so.

To keep burning the fossil fuels that both drive the economy and wreck the global climate, operators of major carbon emitters, including refineries, paper mills, and power plants would have to buy permits from the state or from each other.

Money raised by auctioning those pollution allowances would go to climate-friendly projects like clean energy and carbon sequestration, with at least 35% of the total to benefit “vulnerable populations within overburdened communities,” including 10% for tribal communities.

Devon Connor-Green with the Washington Black Lives Matter Alliance said the measure will help vulnerable communities and let the state begin its overdue transition to a carbon-free future.

“There’s an urgent need to act and address the climate crisis, which has and will impact [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] communities the most,” Connor-Green testified before the Washington House Appropriations Committee.

Other racial-justice groups say auctioning off carbon permits could leave people living near polluting facilities in harm’s way.

Sponsored

“Companies like BP Oil can buy permits or invest in offsets elsewhere instead of reducing their pollution in our communities,” activist Jill Mangaliman with Got Green said. “There are far too many loopholes for companies to abuse this program and get out of being accountable to reducing their emissions at the source.”

In addition to buying allowances, companies can meet up to 8% of the mandated pollution cap, which grows tighter over time, by buying carbon offsets — basically, paying somebody else to pollute less or suck up carbon dioxide on their behalf.

Under the bill, if a company’s actions fail to improve local air quality for polluted communities after two years, the state can mandate direct pollution reductions.

“The declining cap coupled with the additional tools to reduce local air pollution is not something we have seen from other carbon policy proposals in Washington or elsewhere,” said Katelyn Roedner Sutter with the Environmental Defense Fund in Sacramento via email.

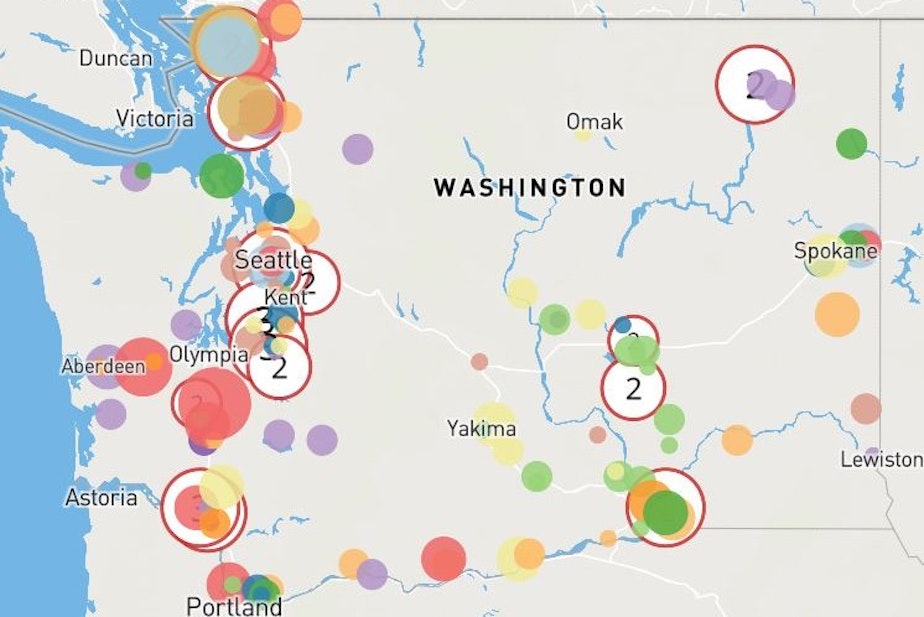

Tap this interactive map from the Washington Department of Ecology to see Washington's worst climate polluters in 2019. Most facilities emitting 25,000 tons or more of greenhouse gases annually are covered by the cap-and-trade law:

Sponsored

Local environmental groups Climate Solutions and the Washington Environmental Council found themselves allied with big polluters BP and Puget Sound Energy in support of the plan.

Opposing the cap-and-trade bill left activist groups like Got Green and 350 Seattle in the unusual position of siding with Republicans as well as aluminum, cement, pulp, and steel manufacturers.

“It will cost important manufacturing jobs,” said Republican Rep. Mary Dye of Pomeroy about the measure before urging a vote against it. “You can find solutions that don’t injure communities, that don’t take away jobs and export them — leakage, they call it — to other places, other countries.”

Big Oil breakup

Sponsored

Five of Washington’s six biggest sources of carbon pollution in 2019 were oil refineries, according to the Washington Department of Ecology.

In 2020, the Western States Petroleum Association, representing oil refineries in Washington, testified against the state's attempts to pursue “multiple overlapping climate policies.”

This year, the association lobbied against a “low-carbon fuel standard” Inslee proposed but stayed neutral on cap-and trade.

The fuel standard would require motor vehicles to gradually transition to low-carbon energy sources such as biofuels or clean electricity.

“We support market mechanisms for carbon reductions,” said Kevin Slagle with the Western States Petroleum Association. “They just need to be good policies.”

BP, owner of the state’s largest refinery and major bankroller of a 2018 campaign to stop Washington voters from adopting the nation's first carbon tax, exited the Western States Petroleum Association in 2020.

Sponsored

A company statement on that rift cited the trade association’s opposition to a low-carbon fuel standard and other climate policies. BP is still a member of the American Petroleum Institute, the U.S. oil industry's main lobby group.

This year, BP lobbied in support of cap-and-trade and did not oppose Inslee's low-carbon fuel standard.

“We are committed to be part of the solution moving forward. The state's chosen both, and we’ll adapt to that market,” said Tim Wolf, a BP lobbyist. “Refineries can adapt and make other products in different ways to lower the carbon footprint.”

Neither Slagle nor Wolf specified how the refineries would meet their obligations to reduce emissions in the years ahead.

Wolf said all diesel fuel made at the BP refinery at Cherry Point north of Bellingham already contains 5% tallow — a beef byproduct sometimes used to make soap and shortening — giving it a lower carbon footprint.

Sponsored

The beefy diesel costs “a little bit more,” Wolf added, and is mostly sold in California and Oregon, states with low-carbon fuel standards in effect since 2016.

Inslee has tried to get Washington state to adopt similar climate measures for years. Together, the cap-and-trade and low-carbon fuel bills were the big missing links in his climate agenda.

“We finally have meaningful climate legislation that reflects the values and priorities of Washingtonians and that respects the science of climate change. It caps and reduces climate pollution across our economy,” Inslee said Sunday night.

The cap would cover about 75% of statewide emissions. Climate-harming pollution from planes, ships, federal facilities, and farm equipment would remain unregulated.

Solid Democratic majorities in the state Senate and House approved the measure, with Republicans unanimously opposed.

“Politically, the scales tipped and Washington's a little more progressive than it was a few years ago,” said Kevin Slagle with the Western States Petroleum Association.

The petroleum association lobbied unsuccessfully to stop the low-carbon fuel standard, which critics say will drive up fuel prices.

Big victory*

The passage of the two climate measures represents a big victory for Inslee, who has watched his state’s carbon emissions increase, not decrease, during his eight years as governor.

In December, Inslee said it was time to “break the [fossil fuel] “industry’s control over policymaking.”

With these new laws, on top of five climate measures passed in 2019, Inslee says the state will be able to meet its legal mandate to cut its heat-trapping emissions 45% by 2030 and 95% by 2050.

For climate advocates, it’s a victory with a big asterisk.

The two climate measures only take effect if the state passes a transportation package funded by a gas tax hike of 5 cents a gallon or more.

State transportation packages usually focus on building highways, conduits for Washington’s leading sources of climate pollution: motor vehicles.

The 2-year, $11.8 billion transportation budget approved by state legislators in April is no exception. It funds wider highways including Interstates 5, 90, and 405 and adds brand-new extensions of state routes 167 and 509.

Former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn called it “climate arson” on Twitter.

The transportation budget includes $236 million, or 2% of its total, in support of electric, alternative fuel, and human-powered transportation, with most of that amount going toward three electric ferries.

The budget devotes $29 million, or just 0.24% of its total, to climate-friendly transportation on dry land.