Citing racial inequities, WA insurance commissioner pushes to end use of credit scoring to set rates

How much you pay for auto, home and renters insurance depends a lot on your credit score. If your credit is good, you tend to pay less. If it’s not so good, you likely pay more.

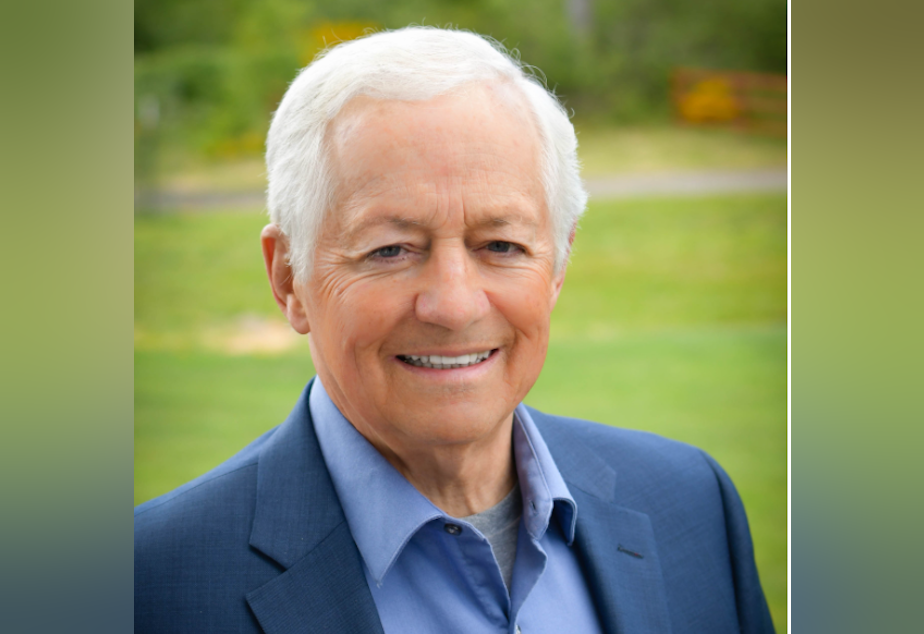

Now, Washington Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler wants to ban the use of credit-based insurance scoring to set rates. He says it’s a matter of racial justice.

“I’ve known for years, it’s been well-documented that this had a disparate impact,” said Kreidler, noting that insurance scoring has been used since the late 1980s.

Kreidler, a six-term Democrat, first proposed a ban on credit scoring a decade ago. He said he revived the idea this year because of the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic and because of the recent push for racial justice.

“The whole Black Lives Matter and racial consciousness certainly helped to elevate it again,” Kreidler said.

Kreidler and other advocates cite studies that have shown a correlation between low credit scores and people of color. They also cite the experiences of individuals like Marie, who asked the public radio Northwest News Network not to use her full name because she works in the insurance industry and fears retaliation.

“I’m a safe driver, my husband and I have a long history of being insured, but I can’t afford the insurance at my own company,” Marie said.

The problem, said Marie, is that she and her husband have a lower credit score due to the fact they’re renters and don’t use credit cards. Marie said she understands why insurance companies rely on credit scores to set rates – credit history is correlated with risk -- but she doesn’t think it’s fair, especially as an African American woman.

Sponsored

“I think that in our community we are less likely to use credit and less likely to be homeowners, we’re less likely to have those factors that would make us appeal to insurance companies,” Marie said.

Currently, Marie pays $460 a month to insure four cars and three drivers through what she called a “substandard” insurance carrier. Even with an employee discount, she estimates she’d pay nearly double that to get insurance through the company she works for.

Marie supports the idea of a ban on using credit scores to set auto and property insurance rates. But the proposal in the Legislature has run into stiff opposition from the insurance industry. At a recent public hearing on the bill, industry representatives defended insurance scoring – which they say uses elements of a person’s credit score -- as objective, fair, accurate and predictive of losses.

“In fact, the use of these scores is the opposite of racial discrimination,” said Tony Cotto of the National Association of Mutual Insurance Companies (NAMIC) in Louisville, Kentucky.

Cotto offered himself as an example.

Sponsored

“I’m a married, Hispanic male in Kentucky who has a law degree, drives a 15-year-old truck and works for NAMIC -- and an insurance score wouldn’t tell you any of those things because it doesn’t matter,” Cotto said. “What matters is how I behave.”

In that same hearing, consumer advocates said that while credit scores may not reveal a person’s characteristics, they are closely tied to income levels and, by extension, to race.

“It replaces or serves as a proxy for race, whether intentionally or not the impact is there, the unfairness is there and the discrimination is there,” said Douglas Heller with the Consumer Federation of America.

Both sides of the debate point to various studies that have looked at the connection between credit scores and race. Some studies draw more of a correlation than others.

For instance, a 2004 study by the Department of Insurance in Missouri found that “insurance credit-scoring system produces significantly worse scores for residents of high-minority ZIP codes.”

Sponsored

And Heller, of the Consumer Federation, told the Senate Business, Financial Services and Trade Committee that people living in Seattle’s 98118 ZIP code, described as the most diverse ZIP code in the country, are paying the highest penalty in the state for credit-based insurance pricing.

However, a 2010 report by the Federal Reserve found “no evidence of disparate impact by race (or ethnicity) or gender,” but did find “limited disparate impact by age.” The authors of that report, though, acknowledged “important limitations” having to do with sample size and the credit history scoring model they used.

While the extent of racial disparities in credit scoring is a topic of debate, it’s clear that scoring people based on their credit history carries a lot of weight with insurance companies. In fact, Kreidler’s office told the Senate committee that someone with good credit and a drunk driving conviction could pay less than someone with bad credit and no conviction.

Kreidler notes that four other states, including California, already restrict the use of credit scoring for insurance. Instead, he said, insurers should invest in other predictive tools like telematics which track a driver’s behavior. Kreidler’s bill to prohibit the use of credit scores by insurers in Washington is sponsored by Democratic state Sen. Mona Das. Twenty other Democratic sponsors have also signed on in support.

Gov. Jay Inslee is also pushing for passage of the measure. Recently, Inslee compared the practice of using insurance scoring to “redlining” – the now outlawed practice of denying mortgages or other financial services to people of color based on where they live. In Washington, it’s already illegal to use credit history by itself to deny or cancel insurance coverage.

Sponsored

Still, the proposal has drawn opposition from minority Republicans and from state Sen. Mark Mullet, the Democratic chair of the Senate Business, Financial Services and Trade Committee.

Mullet said he’d like to find ways to lower insurance rates for good drivers with poor credit, but he worries that if credit scoring is banned good drivers with good credit will see their rates rise. Mullet predicts that would hit older drivers especially hard because he sees a clear correlation between credit scores and age.

“I think the unintended consequence is you would have a huge cost shift of younger consumers having their insurance premiums go down and older consumers having their insurance premiums go up,” Mullet said.

However, Cathy MacCaul of AARP Washington contested that assumption during the public hearing. She testified that older drivers often have lower credit scores because they no longer have mortgages or have stopped using credit cards. MacCaul also said workers 55 and older have been disproportionately impacted by pandemic-related layoffs.

While Mullet doesn’t support the bill in its original form, he said he hopes to advance an amended version out of his committee on Monday. Instead of banning credit scores outright, Mullet’s version would restrict their use to no more than 50% of the weighted factors used to determine rates.

Sponsored

Additionally, Mullet would establish an 18-month moratorium on insurance companies raising rates on people whose credit scores fall due to the pandemic.

But Kreidler said in a statement he can’t support Mullet’s substitute proposal.

“A ban should be on the books in the state of Washington,” Kreidler said. “Nothing less will do to protect the people of Washington at a time when they need it most.”

Sen. Das, the prime sponsor of the measure, said "more bold action" is needed, but also indicated she could support Mullet's amended version of the bill. "It's not the leap forward like we wanted," Das said. "It's a step in the right direction."

Two other proposals in the Legislature, one in the House and the other in the Senate, would require insurers to provide reasonable exceptions to consumers whose credit scores are affected by extraordinary life events including natural disasters, a serious illness or a layoff.