'Somebody who looked like this was here': five immigrant artists who helped shape 2019

It’s the end of the year, and Record producers have been revisiting some of our favorite conversations. Mine were about: immigrants.

Immigration has been in the news, as a talking point and a political football. But I wanted to speak to the people telling the vulnerable, personal, human stories of the places we come to and the ones we leave behind.

To do that, we revisited conversations with a novelist, an illustrator, a musician, and two poets. Each artist is an immigrant or first-generation American, each with their own story of how we arrived at our current moment and where we might be going. You can read a full transcript of the show here. All the music featured in the show is at the bottom of this page.

Alsarah

The hour’s first guest, Alsarah (pictured above), visited the studios as her native Sudan was making history: Omar al-Bashir’s government had just fallen. Although the singer doesn’t consider herself an activist, she notes that art has always been a target of repressive regimes. “Artists are the megaphone of the people,” she says. Her people can be found in many places – in diaspora and along the banks of the Nile.

Alsarah

Marcie Sillman speaks with musician Alsarah, of Alsarah and the Nubatones.

Growing up, “the borders that I was told to adhere to just didn't make sense.” That is, until she began to see manmade divisions differently. “Think of rivers, mountains, forests, oceans. I think of waterways as roads. So instead of thinking of those as blockages, think of them as connectors.”

Her story as an immigrant in America is a familiar one: being in Sudan highlights how American she is, but being in New York highlights how Sudanese she is. Which is not necessarily a bad thing. “The magic of being of one world and in another world: it can be traumatic, but it could also be a magic. And it's up to you.”

Ocean Vuong

is a poet, professor, and first-time novelist. His book, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, was one of the most talked-about books of the year. It’s an epistolary work of autofiction – the protagonist Little Dog is writing a letter to his mother that she’ll never read.

Ocean Vuong

Bill Radke speaks with Ocean Vuong, author of On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous.

Part of the problem involves writing into the pain that families may not want – or be able to – speak about and name. Writing as a child of immigrants is to “betray them in order to preserve them. We write about what they go through and in a way, it exposes those wounds, exposes things they want to cover up. But if we don't do it, it will be lost. Their story will be lost. Who else is going to write it?”

America can be a hall of mirrors, an unpleasant surprise for those who come to these shores. “You think you're walking somewhere, you think you're entering a country, you think you're entering a room. But when you look at the mirror, you're not there.”

The terrifying loneliness of that absence, however, is its own opportunity. “The power of art, and I can only speak as an artist, is that you start to write on the mirror. And even if you write on it and you walk out of the room. Someone could read the mirror and say, ‘Wait a minute. Somebody was here! Somebody who looked like this, was here.’”

Jane Wong’s

mother escaped famine to come to America and help start a Chinese restaurant in New Jersey. But the experience of hunger doesn’t leave a family’s DNA, or memory, so easily. Wong explored those themes in a poem that she says is inspired by themes of hunger and gluttony across generations. It’s called After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly.

Jane Wong

Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong speaks with poet Jane Wong, whose show at the Frye was called After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly.

“I wanted the poem and the title to be long, voracious, hungry.” In it, she imagines her ancestors consuming everything from the frontier to her flip-flops to the American Dream itself. Some of those things, she says, are emptier than others.

The poem was the basis of an eponymous gallery show this summer in the Frye Art Museum. A large golden table is decorated with bowls containing snippets of the poem – some full, some empty. Above hangs a chandelier with a nod to an experience well known to immigrants everywhere: the hoarding of plastic bags because – you never know – you might use them someday.

The space is capped with a large neon sign that says in Chinese: Have you eaten yet? “And that basically is the same way of saying,’How are you?’,” says Wong. “And I love that way of greeting someone. If you didn’t, you have to explain why you haven’t eaten and then you will be fed.”

As a writer, she also struggles with the question of silences, and whether it’s fair to cause her family pain. But she doesn’t want their histories to be forgotten. “My uncle’s a fishmonger in a market in the ID. And I think about how, sometimes, invisible he is behind the counter, scaling fish. And to have him be present in the gallery space like that, and beyond […] all I can say is that I hope it gives them that sense of feeling seen, being there.”

Immigration is about many things – but fundamentally, it’s about place.

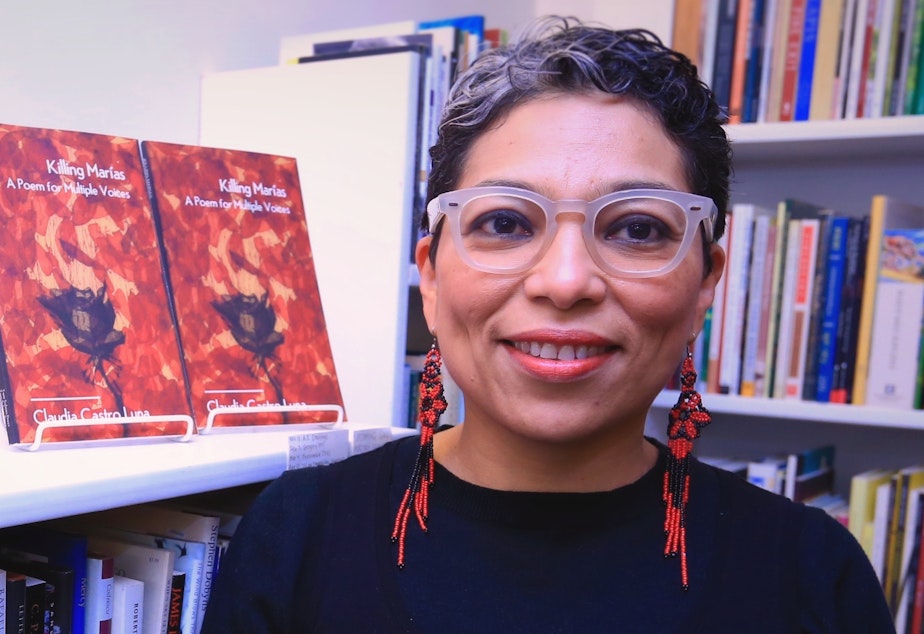

Claudia Castro Luna,

Former Seattle Civic Poet and current Washington State Poet Laureate, has dedicated her life to spaces: first as an urban planner, and then as a poet who brings cities to life. In both of her official roles, she’s solicited poems from residents of Seattle or Washington and used them to build maps of the places they call home. Her latest is called Washington Poetic Routes.

Claudia Castro Luna

Bill Radke speaks with Claudia Castro Luna, Washington State Poet Laureate.

Many of the places she visited are rural, like Brewster or Waitsburg. None of that looks anything like the home she fled due to war. “For me, El Salvador exists in the imaginary because I look out the window and nothing here looks like El Salvador. Sometimes I tell the kids what it was like for me to grow up in a tropical country as a way of explaining to them what I mean by place, and what I want them to think about and capture in their poems.”

In her travels she’s seeing these places through her own eyes as well as those of the poets, as with one poem called "A True Account of Wood-Getting from Up the Chumstick", in which two friends have a slightly bloody adventure while collecting firewood.

“I could entirely see that – perhaps because I have been in Leavenworth and heading back to Seattle after a reading, in the afternoon, on those roads, by myself, through the forest. When I read that, I just could feel the darkness of the forest around them, and the quietness.”

These are postcards from around the state, snapshots of place and of history, with which she hopes to bring deceptively static maps to life.

Malaka Gharibgrew up in Cerritos, California, where she was both surrounded by first generation kids like her and entirely alone.

At first the Filipino-Egyptian-American tried to identify with whiteness, wanting to be like the kids in Dawson’s Creek and Americanizing the pronunciation of her name. “Like, I remember looking in the mirror and saying ‘Malaka. Gur… GARE-ib. Malaka Gharib, like Arab!’”

Malaka Gharib

Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong speaks with Malaka Gharib, journalist and author of I Was Their American Dream.

But as time went on, Malaka – that’s “like Monica, but with an L” – learned to embrace the glorious messy complexity of her identity. She explores that journey in her new graphic memoir, I Was Their American Dream.

In the book, Gharib shares her parents’ story and makes some cheat sheets for her movements across worlds. With Egyptians, sit separately from the men. With Americans, be on time. Filipinos can and will comment on your appearance. And all three eat with their hands, an illustration of pizza reminds you.

That crossing of cultures led to some things she never talked about in California, like seeing the Second Intifada from a beach vacation with her father near the Sinai Peninsula. But now, Gharib says our one-dimensional views of each other prove that we’re not talking about race enough. “I want people to know when they meet me that this is what a Filipino-Egyptian-American, with a Muslim father and a Catholic mother, looks like.”

MUSIC