At the birthplace of Seattle karaoke, two different visions for the future of the CID

Chinatowns across America are being erased by development. As rents rise, they’re growing more white and affluent. That can threaten small businesses.

At the same time, developers argue that they bring new life and prosperity to aging neighborhoods. Elderly grandparents in subsidized housing, they say, would love to have places for their descendants to live nearby.

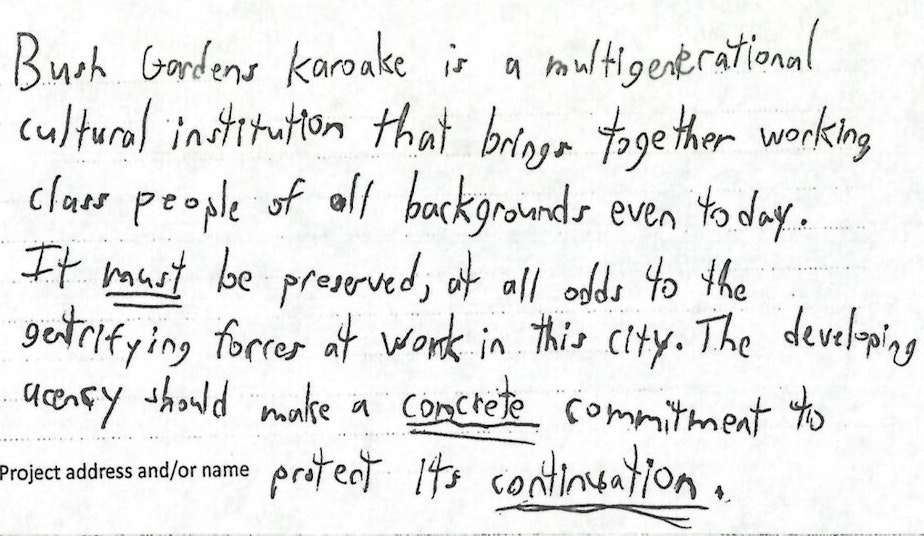

In Seattle's Chinatown International District (also known as the CID), the conflict can be seen most clearly at the epicenter of the resistance: the city's first karaoke bar, Bush Garden.

Developer James Wong says he's driven to build the 17-story Jasmine residential tower in the Chinatown International District by two childhood experiences.

One stemmed from living in Wong's childhood apartment on Beacon Hill, above a church above his elementary school.

“All I would have to do to go home is walk directly across the street,” says Wong. “But instead of doing that, I walked around the block, went through the alley, and went through the back. Because I didn’t want my friends to see that I lived there. And I don’t know where it came from, I was 10 years old, but I felt a lot of shame, living in what I perceived at the time to be an ugly apartment building living on top of a church.”

Wong remembers seeing Seattle’s towers from the bus and comparing them to his shoddy apartment.

“And I said, ‘You know what? Some day I’m going to be able to afford to live in some of these,’” remembers Wong. “’Some day, I’m going to build apartments and build these buildings that people feel proud to live in.’”

The kind of person that would live in the Jasmine, Wong says, is a young professional whose grandparents live in subsidized housing in the CID. On weekends, his tenants can visit their elders and have dim sum together.

The second experience for Wong involved his father, who had always wanted to own a restaurant. Eventually, his father opened the restaurant, but he didn’t have the expertise to run the large space and staff efficiently, and the restaurant failed.

Sponsored

“He was never the same after that,” Wong says.

Wong says immigrant business owners need small retail spaces in order to succeed.

“If the restaurant is about 1,000 square feet, and you could manage it with a skeleton crew, maybe the husband and wife with one or two staff and then the kids can help out on the weekends and after school," Wong says. "In America, that's small. But in Asia, that's normal size."

"Man, that’s the dream I have for this community," Wong continues. "That’s the kind of thing that could build this community and make it even better."

Directly below Wong’s office on the future site of the Jasmine, Karen Sakata runs Bush Garden restaurant in an earthquake-damaged building. It has one working sink in the men’s bathroom and peeling wall finishes dating back to the building’s heyday in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. But to move beyond first appearances and understand this place and the CID, Sakata says you have to sing karaoke.

This was Seattle’s first karaoke bar, and when Sakata started hosting here, music was on eight-track cartridges. She still hosts on weekends, and begins each evening with a song, something that sounds to me a little like a Japanese version of Doris Day.

Over the course of the evening, people turn in their slips of paper with song requests and approach the microphone. Some are regulars, arising from solitary positions at their own tables; others from clusters of friends trying karaoke here for the first time. Sakata plays air guitar, or accompanies them on her tambourine. Anything to coax them into feeling free, anything necessary to make this evening the best it can be.

“For me, the spirit of karaoke from Japan is, it’s not about being good, it’s about sharing,” says Sakata, “And so in Japan, when everybody goes out, everybody has to sing one song. It doesn’t matter, you can’t say I don’t have a good voice, it doesn’t matter – it’s just part of giving to your group.”

This is how karaoke helps us understand the CID. It doesn’t cost much to get in. People come here from all different countries and backgrounds. And sometimes, it all just kind of vibrates together.

Karaoke won’t be going on much longer at this space. When the Jasmine begins construction, Sakata will have to move Bush Garden to a new space. She might have stayed on as a tenant in the base of the new tower, but said she doesn’t believe high rises belong in the CID.

Instead, she plans to move Bush Garden to an affordable housing development that could break ground in the CID this summer. The new building will be called "Uncle Bob's Place." It's named for Bob Santos, a popular community leader and Bush Garden regular who died in 2016.

Sakata says in Chinatowns across the country, parts of the neighborhood’s history are getting erased.

Sponsored

“I feel like this space is really special," Sakata says. "And it’s been filled with so much energy or spirit over years. And so, even though we may move up the street, when it comes time to develop here, I’m not superstitious, but I do believe there’s such a thing as a spirit in place, in location. And I think this building and the businesses that have been here and the type of things that have gone on here also tell the story of immigrants in Seattle. The way people come together.”

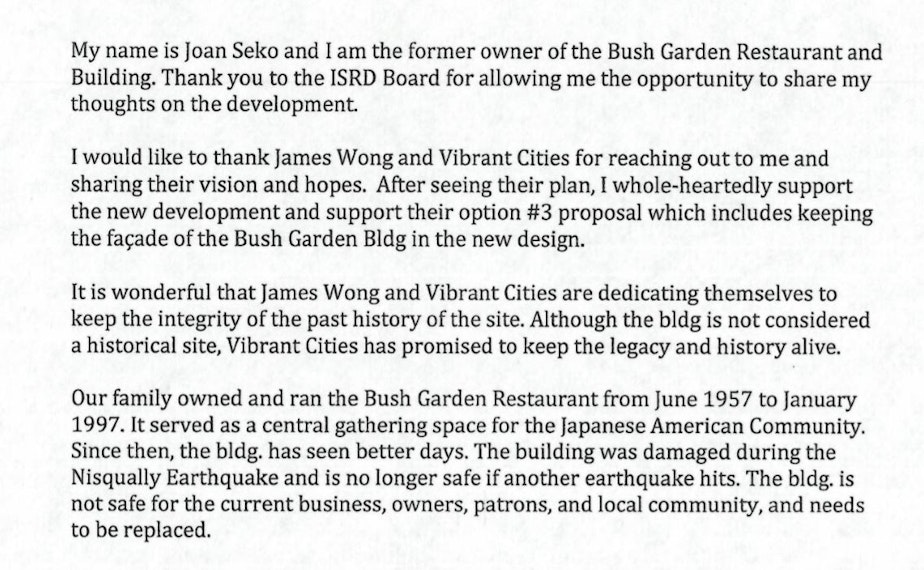

Though Bush Garden is leaving, Sakata’s not going quietly. Her bar has become ground zero for a small resistance movement, a group James Wong describes as “a very vocal minority” in a community he says largely supports the Jasmine project, offering letters of support as proof.

Long after the karaoke ends, Sakata gathers with local activists in an empty booth at Bush Garden. They’re strategizing about how to tell the story of what’s happening in America’s Chinatowns, and why it’s important that they survive. They're planning a week of rallies and marches and guerrilla art events in coordination with other Chinatowns across the country.

Nina Nobuko Wallace is one of the group’s organizers.

“We’re not against development,” she tells me. But, she says, you’ve got to understand the history.

She lays out how Seattle's CID was shaped by redlining, city neglect and exclusion. That created a strong bond between this place and Asian Americans who called it home, as well the African Americans who’ve also found a place there. Nobuko Wallace says it’s hard to see that go away when luxury condos drive up rents, which can drive out minorities and their businesses.

Seattle has designated the Chinatown International District as having a high risk of displacement. Over the last decade, the Asian population in this neighborhood has dropped as the white population has grown.

A recent wave of development began with the Koda Condominium Flats that just broke ground down the street (marketing tagline: "Own the City"). And then there’s the Jasmine, a 17-story building planned for this spot, which will include market-rate condos or apartments.

In other cities, similar groups are calling for moratoria on luxury condos. Here in Seattle, activists say luxury residential developments should offset their impact by offering community gathering spaces. They want community oversight groups to have more say over what additional concessions should be demanded from developers.

Activist Yin Yu puts it this way: “Any of these developments that are coming in, they should be giving back to the community. They need to be giving back to the community, because they will benefit and profit off the culture of this community.”

Which brings us back to James Wong, the Jasmine’s developer. “I want to build something great for this community," he says. "Because I grew up here, it’s important to me. I want to build something that we’re proud of.”

Wong has expressed laudable ambitions for his building, but activists meeting at Bush Garden say most of those promises rely on him and his decisions down the road.

"His story is that he wants to make this place more vibrant," Sakata says. "But I’d say to him, ‘Your family wouldn’t have been able to afford to live here. And I would really think that if you wanted to honor that, you would build something different.'"

"I don’t know if you can make a 17-story building feel like community," Sakata says.

Wong is frustrated by that thinking. He says the CID is full of affordable housing already. He says what the neighborhood needs is to bring in new people and new money so it can support local businesses like Bush Garden.

“I know what my role is – I’m a market-rate developer,” Wong says. “It’s what I do.”

He knows that means getting criticized, sometimes.

“What’s important here is that my heart is right," Wong says. "I’m not trying to build the cheapest, most profitable project. I want to add to this community.”

Even if he chooses only to build expensive condos in his tower, Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability rules mean he’ll pay funds so that affordable housing can be built at another property.

The challenge for this neighborhood will be for it all to gel together like a great karaoke night, when all those new people come in.