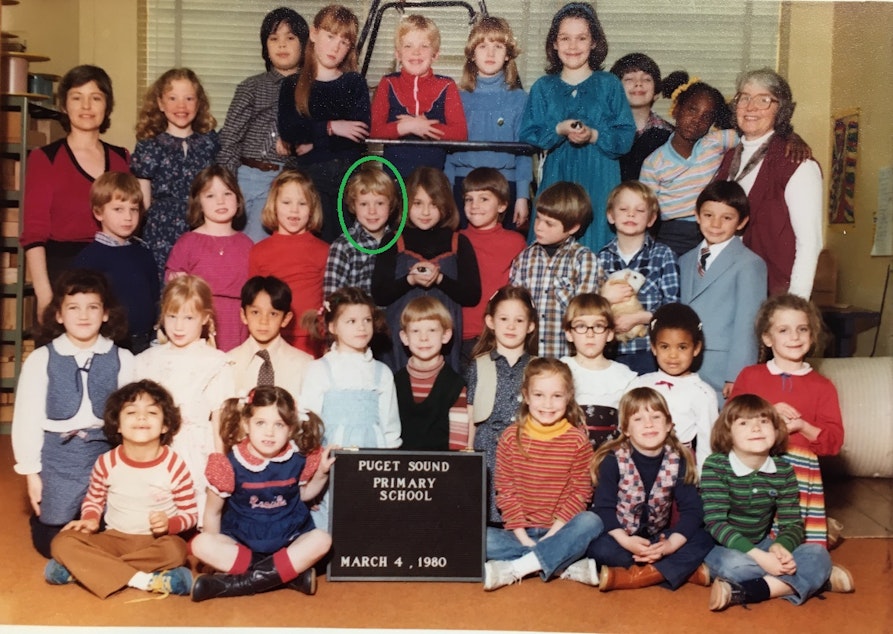

At age 6, he and his classmates fled Mount St. Helens. 40 years later, this reporter recalls that day

Olympia Correspondent Austin Jenkins was a first grader on a school camping trip near Mount St. Helens when the volcano erupted on May 18, 1980.

Austin recently unearthed his scrapbook from that time and interviewed several others who were on that memorable trip. On this 40th anniversary of the eruption, Austin recounts their harrowing escape.

On May 18, 1980, I was 6 years old and about 20 miles, as the crow flies, from Mount St. Helens.

My small, private elementary school, Puget Sound Primary School, had taken an end-of-year trip to Camp Cispus, a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp on the Cispus River southeast of the town of Randle.

On that spring Sunday morning, we were packing to return home to Seattle after a couple of days spent in the woods studying lichen and pine cones and playing games like tug of war.

Even though Mount St. Helens had been bulging for weeks, the camp was thought to be outside the blast zone.

“That was assuming it went straight up, instead of sideways.” said Dr. Laird Patterson, a retired Seattle neurologist who was a parent chaperone on the trip.

Sponsored

At about 8:30 that morning, the mountain blew sideways.

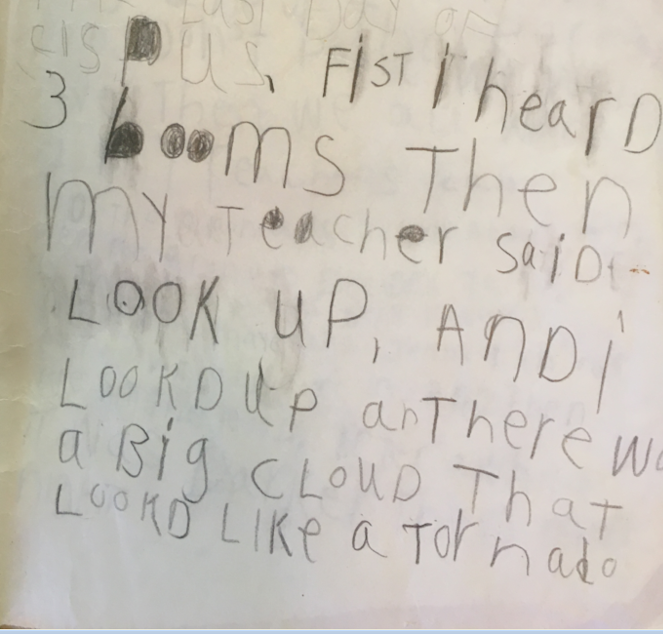

“First, I heard three booms,” I later wrote in my first grade journal. “Then my teacher said, ‘Look up,’ and I looked up and there was a big cloud that looked like a tornado.”

Others there that day don’t recall hearing the mountain erupt. But they do remember the cloud.

“It was absolutely the most frightening thing that I’ve ever seen in my life,” Patterson said. “It’s like seeing the world’s biggest tidal wave coming towards you.”

Sponsored

“You could see this roiling coming across the sky and we knew what it was,” recalled Sharon Wagner, one of two teachers on the trip and a co-founder of the school.

The camp’s alarm bell rang – a signal to gather in the playfield.

“Everyone ran to the field and one of the parents said: ‘Don’t panic, we will live,’” I wrote in my journal.

The ash cloud turned day into night and clumps of wet debris began to fall out of the sky. At age 6, I thought they were rocks. There was also a burning, acrid smell, remembered parent Kit Bakke.

“And, of course, we wondered if it was toxic or not,” Bakke said.

Sponsored

Our group of students, teachers and chaperones regrouped in one of the cabins to decide whether we should shelter-in-place or evacuate.

“All we knew is that we had 30 kids to protect … and we had to make a decision in a very short period of time about what we were going to do,” Patterson said.

Patterson had read the book “Fire and Ice: The Cascade Volcanoes” and recalled that when Mount Mazama erupted more than 7,000 years ago, creating Crater Lake, the surrounding area was buried in deep ash.

“I was anxious to get as far away from it as I could,” Patterson said.

The decision was quickly made to evacuate.

Sponsored

“The grownups talked about staying, then the grownups decided to go,” I later wrote, matter-of-factly, in my downward slanting, first grade pencil scrawl.

Oddly, I don’t remember my 6-year-old-self feeling panic or fear in the moment.

What I do remember is climbing into a Volkswagen van, driven by Bakke, with several other kids and heading out in a convoy of parent chaperone vehicles. The windshield wipers labored against the falling ash. We marveled that it was so dark you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.

“It was just literally like you were inside a black velvet bag,” said Patterson who was driving a Volkswagen Rabbit loaded with five kids. “There is no dark like it.”

The headlights barely illuminated the narrow road ahead.

Sponsored

“It was like having your headlights up against a concrete wall, the [ash] fall was so thick,” Patterson said.

Dr. Laird Patterson

Hear Dr. Laird Patterson describe evacuating Camp Cispus with a car full of kids during the Mount St. Helens eruption on May 18, 1980.

The darkness was broken only by flashes of volcanic lightning.

Within minutes of leaving the camp, Patterson was already second-guessing the decision to evacuate, imagining the car breaking down and being entombed in ash.

“That certainly preyed on my mind,” Patterson said.

As the caravan crept toward the town of Randle, at least a couple of the cars did break down after choking on the ash. One of the drivers, Sheila Bender, and the children in her charge abandoned their disabled car and squeezed into a station wagon that had been following them.

Bender’s daughter, Emily Menon Bender, who is now a University of Washington professor, described the tight fit.

“I was sitting on top of some other kid in the middle seat and my mom was on top of me,” Bender said. “I feel bad for whoever that other kid was.”

Soon they spotted a house and stopped. The family, with a walk-in closet full of provisions, fed them spaghetti, canned peas and milk.

“I don’t remember being scared, but I do remember everything I ate that day,” Bender joked in a recent phone call.

The rest of the caravan eventually traversed the 11 or so miles back to Highway 12 and the town of Randle.

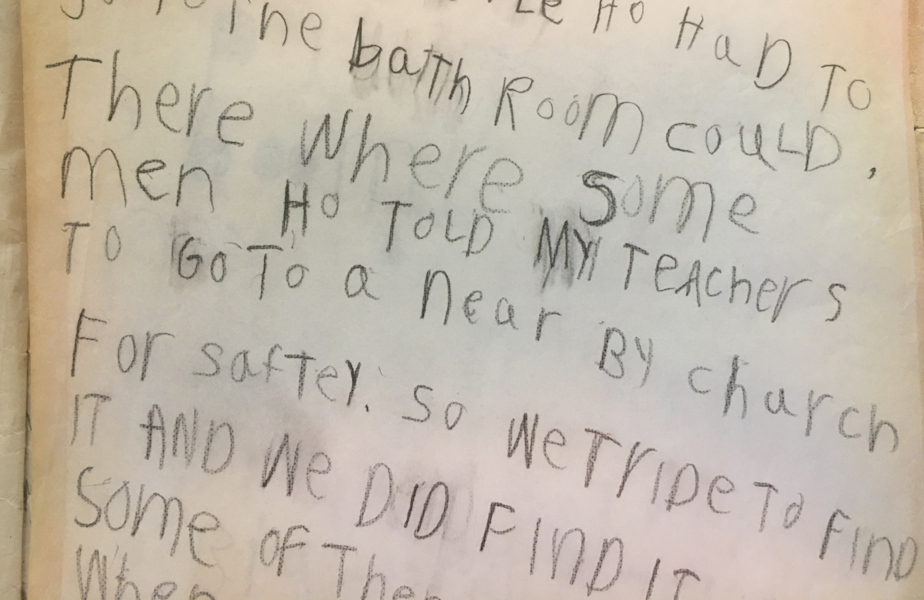

In Randle, according to my journal, we stopped at a gas station where, “There were some men who told my teachers to go to a nearby church for safety.”

“By then the ash was, like, ankle deep,” Bakke said. “It was blanketing the countryside, it looked like the moon.”

Once at the church, we took refuge in the basement. But not everyone was accounted for. Somehow, along the way, Patterson’s carload got separated from the group. They ended up eating hamburgers and ice cream in a local tavern.

“We did split up, not intentionally,” Patterson said.

Eventually, the entire group reunited at the church after a series of phone calls to an emergency contact in Seattle who relayed messages about everyone’s location.

While we kids drew pictures using the Sunday school art supplies, Bakke said the adults once again debated what to do.

“The time in the church basement was in some ways the most interesting,” said Bakke, who was then a pediatric nurse and is now a writer in Seattle.

Kit Bakke

Hear Seattle writer and former pediatric nurse Kit Bakke describe the debate over whether to stay sheltered in a church basement in Randle, Washington or try to make it back to Seattle following the eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980. Bakke was a parent chaperone on a school trip that had to evacuate Camp Cispus which was in the blast zone.

Once again, it was a question of whether to stay or go. The adults had lots of questions.

Could there be more eruptions? Was there danger of a magma flow? Would the air make us sick (there was special concern for a student with asthma)? Might the National Guard arrive and rescue us? How panicked would the parents back home be feeling?

With most of the emergency response focused further south along the Toutle river, there was no one to answer these questions or guide us out of the volcano zone.

We were on our own.

After a couple of hours at the church, the single toilet had backed up and efforts to flag down motorists along Highway 12 for more information had failed. The consensus was to press on toward Seattle.

“We had to make the best decision we could,” said Wagner, whose 12-year-old daughter was also on the trip. Before leaving, the adults tore up old sheets the church had provided to make masks. The strips of sheets were dipped in water and tied around everyone’s faces.

Departing in five minute intervals from the church, to keep the cars spaced due to limited visibility, our convoy headed west on Highway 12 toward Interstate 5. Patterson took up the rear. Somewhere outside of Randle, a speeding pickup plowed into the back of the Volkswagen Rabbit. The impact spun the compact car halfway around.

“I had five kids in that car and three of them in the back seat, we’re just lucky none of them were hurt,” Patterson said.

Eighteen miles later, we arrived in the town of Morton where we were directed to a fire hall. My memory of that stop is that I ate several slices of white bread slathered with butter, a treat since my mother only bought whole wheat bread at home.

At the fire hall, there was a television with the news on -- the first chance to see the scope of the eruption. But Wagner said there still wasn’t anyone to advise them on what to do. Once again, they made the decision to keep going.

Leaving Morton, our caravan encountered a roadblock.

“We talked them into letting us go,” Wagner said.

A few more miles down the road and we emerged from the shroud of the eruption into bright blue skies and sunshine.

"All of a sudden it was just amazing, it was clear," Wagner said. "There wasn't any ash. It was just like from night to day."

I don’t have any recollection of the remainder of the trip home, but I do remember arriving back at our school that evening – hours after we had begun our evacuation.

Our parents were waiting. At least one TV crew was there to capture the moment. Before we headed for home, we scooped ash off the bumpers of the cars into plastic baggies as a keepsake. That night we stayed up to watch the 11 p.m. news. I’ve often said that’s the moment I decided I wanted to be a reporter.

Recently, video of that homecoming surfaced. It was shot by the late Joseph Sullivan, the father of my classmate Kathleen Sullivan who posted the video to YouTube.

In my Mount St. Helens scrapbook, I discovered a couple of newspaper clippings. One is a first person account, headlined “My Teachers and I Ran From the Ash,” by the nine-year-old sister of one of my schoolmates who was on the trip with us.

“All of a sudden big white clouds came out of the sky,” she wrote. “The fire alarm went off. All the little kids ran in different directions. The grown-ups ran after them and caught them.”

Seattle P.I. reporter Gaye Vandermyn also wrote up an account of our escape from the volcano, noting that one of the parent chaperones had observed a lack of birds singing in the hours before the eruption.

“That strange calm in the woods was the first clue. Within half an hour, Mount St. Helens, about 20 miles southwest, blew its top,” the story said.

The story also quoted Wagner and our other teacher, Billie Johnston.

“I ran across the fields yelling that Mount St. Helens was erupting,” Johnston told the paper. “I wanted people to come and see it.”

“Within five minutes, stuff was falling all around,” Wagner said. “We started throwing people and things in the cars but by this time it was so dark you couldn’t see at all.”

Over the years, I’ve occasionally revisited with my mother, Victoria, why she let me go on the camping trip.

“I had no idea the proximity of the volcano to Camp Cispus -- none,” she told me recently. “I don’t know what I was thinking that I let you go off and only vaguely knew where you were going.”

My father’s recollection is they spent that Sunday canoeing on Seattle’s Green Lake with my younger brother, oblivious to the natural disaster unfolding 180 miles to the south.

Over the years, Wagner said she's been asked about the wisdom of taking a school group to a camp so close to Mount St. Helens. She noted the bulging mountain had become something of a tourist attraction. She also said our parents had been briefed beforehand about where we were going and what we'd be doing.

"Nobody objected," Wagner said. "It just wasn’t considered to be a problem at all. That’s why we went.”

Sharon Wagner Excerpt

Hear retired Puget Sound Primary School teacher and co-founder Sharon Wagner describe the decision to proceed with a school camping trip to Camp Cispus near Mount St. Helens in May 1980. On the last day of that school trip the volcano erupted, forcing the school group to evacuate.

Sheila Bender, one of the parent chaperones, noted that then-Gov. Dixy Lee Ray was a scientist by training and had put a relatively small safety zone around the volcano.

“I think it was trust in the governor,” Bender said.

In fact, Bender and Wagner both told me the plan had been to stop at an observation site to see the steam coming off Mount St. Helens before heading home that Sunday.

Later, Bender, a Port Townsend-based author and poet, would memorialize our misadventure in a poem.

At breakfast, a cathedral of trees, sunlight over the high arches.

Then millions of grey golf balls falling and blackness like a cave.

In front of us the tail lights of slow cars fading … ash piles on my windshield, my tires slip like pallbearers in brand new leather soles.

I ask the children to sing a song …”

Sheila Bender

Hear poet Sheila Bender read her poem about evacuating with her daughter's school group from Camp Cispus following the eruption of Mount St. Helens on May 18, 1980.

Over the decades, I’ve told my story about evacuating on TV, on the radio, at public events and, in recent years, to my kids. I even once wrote a graduate school application essay about the experience. I’ve also climbed the volcano and peered down into the crater. And once, I detoured off Highway 12 at Randle to visit Camp Cispus. I joked to my travel companion that I needed to confront my childhood trauma.

While I’m still in touch with a couple of classmates from Puget Sound Primary School, it wasn’t until this year, as the 40th anniversary approached, that I started trying to reach some of the adults who were part of this defining childhood experience.

Hearing the story from their perspective suddenly filled in a bunch of blank spots in my own memory and served to correct a number of misperceptions I've had since first grade.

The conversations were easy and it was fun to catch up. We all seem remarkably untraumatized by what happened. But each anniversary of the eruption also holds special meaning. It's become “sort of a personal family holiday,” said my classmate Emily Menon Bender. On this 40th anniversary, I plan to reflect on the 57 lives lost on May 18, 1980 and on my good fortune that I escaped, no worse for the wear, and with a good story to tell.

Next year at this time, in a life comes full circle moment, I expect to send my son off to Camp Cispus for his end-of-year fifth grade class trip.

This story has been updated.