‘American policing dates back to the formation of the slave patrols,’ says former Seattle police chief

Tear gas works, said Norm Stamper, the former police chief of Seattle. It disorients protesters, and causes them to scatter.

But it also really ticks people off, provoking, Stamper said, “an intense reaction to the very tactic itself.”

Stamper was police chief in 1999, at the time of the World Trade Organization protests. He recalled the moment when the protesters turned on police.

There was an intersection occupied by anti-globalization protesters, he said. “We warned them that if they did not vacate that intersection, we would in fact use tear gas against them.”

The protesters did not leave, the police sprayed them.

“When we used the tear gas, the focus was no longer child labor laws or other ills of globalization, but rather, the police,” Stamper said.

Stamper told KUOW’s Bill Radke that it’s important for police forces to be talking with community members long before an event might happen – to create bridges between the two.

“If that relationship is solid, is strong, and is carried into the moment, the chances of broken windows and looting and police cars are reduced,” he said.

Stamper said one way to de-escalate a situation is to back up, as Seattle Police did on Day 11 of protests.

“That's not part of the central nervous system of American policing,” Stamper said. “The idea behind policing a protest is to take the upper hand, and hold that upper hand for the duration of the protest.”

He said he, too, has that instinct, having “grown up in the culture of policing in San Diego for 28 years, to Seattle for six years.”

Stamper said he would disavow tear gas altogether, or any policing tactic for that matter. He called a blanket refusal to use certain tactics “foolish” because if people are in danger, “of course you’re going to respond physically.”

Stamper said police must asked themselves, “Is what we’re doing today working?”

He says no. The relationship between white cops and people of color, particularly Black people, he said, is abysmal.

Stamper pointed to the history of policing:

“The institution of American policing dates back to the formation of the slave patrols where local police were actually assisting the slave patrols if not replacing them,” he said.

White people might say that was a long time ago, Stamper said, that trainings, policies and psychological screenings have improved.

“I would ask, ‘How's that working for us?’” Stamper said. “How's it working in the relationship between young people. poor people, and black people particularly?”

He said it’s necessarily “for all of us to take a breath and ask whether or not policing, or public safety, can be modified.”

Stamper said that the protests, beginning on May 25, make him believe that we will not return to traditional policing.

“This is the first time in my adult life,” he said, “that there has been an opportunity until now to restructure policing. And yes, that means police giving up ceding a certain degree of power that they currently enjoy.”

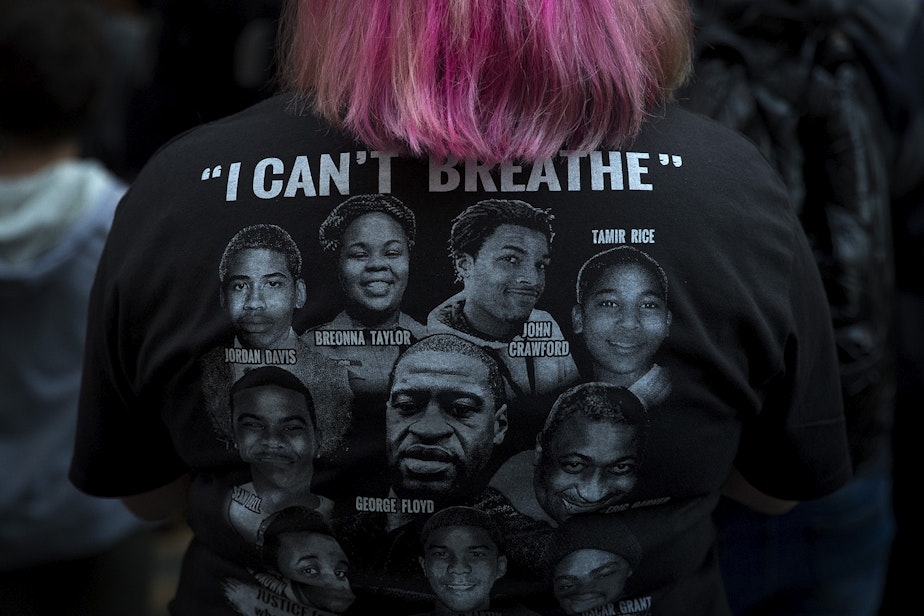

When people watched George Floyd killed by police, Stamper said, they concluded that “something is just terribly wrong with the institution.”

He said he now agrees.

“Something is toxic, and something is terribly wrong with the system of policing.”