Amazon drones can't make city deliveries. The company must first solve machinery falling from the sky

The Federal Aviation Administration says Amazon can now deliver packages to customers by drone — that's in select rural places where few people live.

To deliver in cities, Amazon must first convince the government that its drones are safe enough to do so, in the event they experience sudden catastrophic failure.

This week, it was announced that Amazon has the Federal Aviation Administration's permission to send packages to customers by drone. There are a lot of restrictions, however, on where and how the company does that. In other words, Seattleites will not be receiving packages by drone anytime soon.

Amazon Prime Air was already testing deliveries on private land. But they weren’t certified to deliver to actual customers yet.

But now the Federal Aviation Administration says that while drone deliveries are proving to be pretty safe, there are still unresolved questions. The agency will let Amazon deliver to customers — but only if the drones don’t fly over any buildings, people, or cars.

Safety concerns

Amazon says the drones are safe. But they each weigh 88 pounds, which is about the weight of a standard lawn mower — and they’re 400 feet up in the air, most of the time.

Sponsored

So if something goes wrong and they fall out of the sky, over a city, that’s potentially very dangerous.

One expert was concerned enough that he wrote a letter to the Federal Aviation Administration. His thinking goes like this: Amazon delivers over half a billion packages in the U.S. each year. When you look at Amazon’s own numbers, we can expect 5,000 drones to fall out of the sky every year, maybe even 10,000.

KUOW reached out to expert Guido Fuentes to understand what this means. Fuentes works for a company called Prism, which advises airlines and drone operators as they work towards Federal Aviation Administration certification.

“Basically, the FAA leaves it up to the drone manufacturer and drone operator how to mitigate the risk of flying over populated areas,” he said.

When it comes to legalizing drones, he said one of Amazon’s main challenges: Convincing the Federal Aviation Administration that its plans are safe.

Sponsored

How to solve a problem like a lawn mower falling from 400 feet

How Amazon addresses these risks is a closely guarded secret. The flight manuals the company shares with the Federal Aviation Administration are proprietary.

After all, the race to be the first to deliver by drones has the heat and competition of a space race. Amazon fired the starting pistol, but Alphabet (Google's parent company) and the United Parcel Service got federal approval first. Amazon was third, and half a dozen other drone companies are nipping at its heels.

Other stakeholders have complained about Amazon's level of secrecy, when it comes to drones.

Sponsored

Last year, Boeing complained to the Federal Aviation Administration that Amazon's petition does not adequately describe "the reliability standards for the sensors and algorithms upon which the system is dependent, and it does not describe the data sources and associated data fidelity for flight planning, terrain mapping, or object identification."

Because of this secrecy, we don’t know for sure what approach Amazon has chosen. However, we can get some idea of how Amazon thinks through these problems by examining its patents.

One idea they considered was giving the drones a sort of controlled “self-destruct” ability.

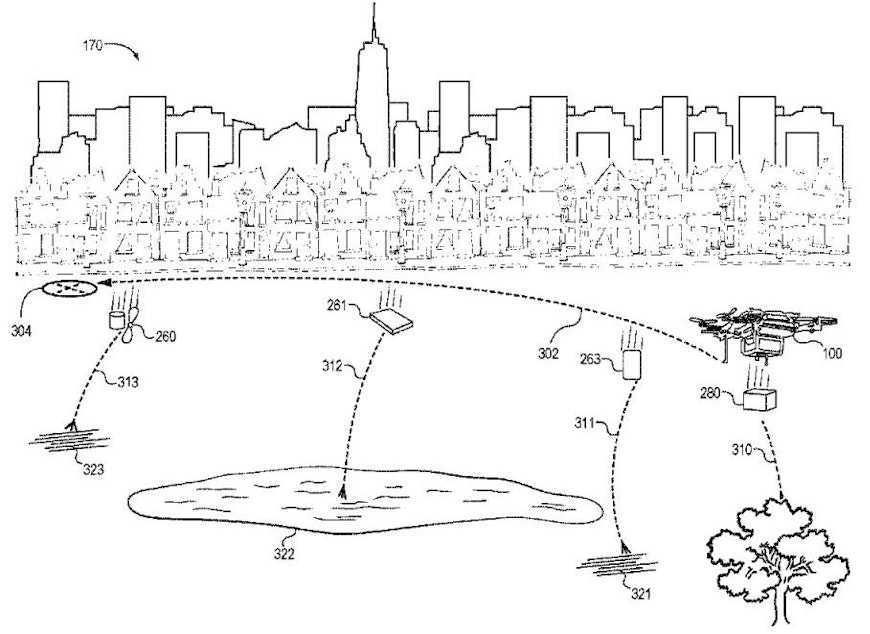

The idea is that if the drone experiences catastrophic failure and is unable to safely land, the drone would scope out the ground below, and look for places where it could jettison its parts. And then it would blow up, sending the heavy motor towards, perhaps a tree, sending the carbon fiber ring into a duck pond, and then sending the package to a grassy ballfield.

Sponsored

But even a piece of a lawn mower is still dangerous if it falls on you. So it seems unlikely that this is the solution Amazon would choose to satisfy the Federal Aviation Administration. But their patents are full of thought experiments like that, presenting the question: What if we did it this way?

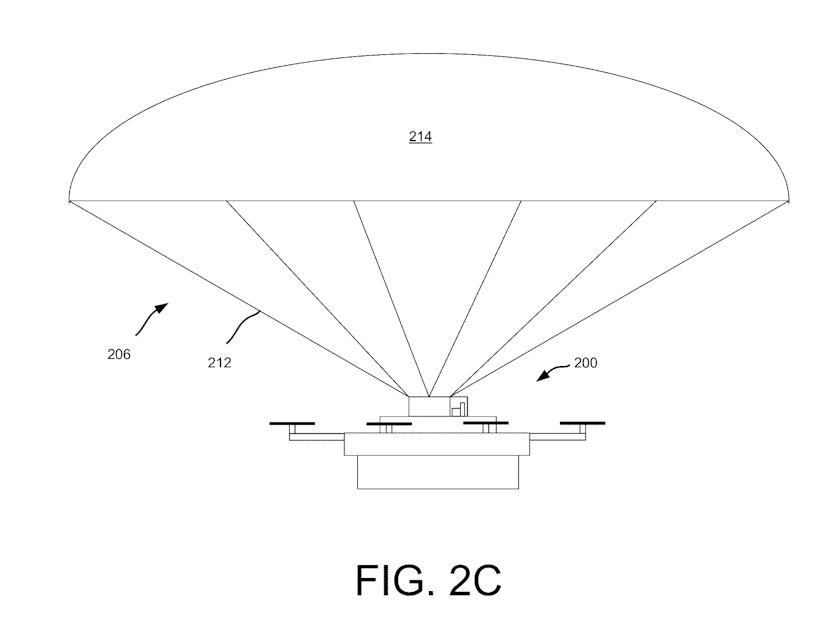

Fuentes, the drone expert, said that most drone manufacturers are opting for a simpler solution: a parachute. And that may end up being what Amazon chooses. But parachutes aren’t foolproof either. A lawn mower parachuting onto the freeway, for instance, could still cause a lot of damage.

Another challenge Amazon had to think through: What happens if the drone’s camera goes out, and it has to do an emergency landing?

Again, we don’t know what their chosen solution is, but one idea they put in a patent looks a lot like a maple tree in the fall. You know those maple seeds that fall slowly to the ground in a spiral because they have what look like helicopter blades on them?

Sponsored

Well, imagine a cluster of small beacons – shaped like those helicopter seeds.

If the drone’s camera goes out, it ejects a bunch of those beacons, which flutter to the ground, and send back a signal to the drone, telling it the shape of the ground below and where it can land.

Next steps

Amazon has to demonstrate to the Federal Aviation Administration that its drones are safe. And right now, the agency wants a team of humans closely monitoring these drones. Including a pilot who is responsible if something goes wrong.

But Amazon wants to automate most of the process, because these drones are robots.

Proving to the Federal Aviation Administration that these robots are better at making safety decisions than people could take a couple more years, at least.

Fuentes, the drone expert, said we can expect to see drones operating first under rules designed for airplanes.

For example, they’d fly in designated corridors. That means during these early years of drone delivery, you could find yourself living beneath a drone superhighway.

But over time, he expects drones will demonstrate their ability to avoid crashing into each other, and the traffic management systems that track where all drones are at any given moment will mature.

When that happens, he says drones may be allowed to leave their designated highways, truly choosing the most efficient route.

KUOW’s Joshua McNichols covers many topics including technology and its impact on cities and the people who live and work there. One question he’s looking into is what replacing delivery drivers with drones will mean for workers. Amazon often claims automation leads to more jobs, not less.

If you have insights to share, please reach him at jmcnichols@kuow.org.