Affirmative action returns to Washington ballot after more than 20 years

In 1998, Washington voters overwhelmingly approved Initiative 200, which effectively ended affirmative action in the state.

Now, 21 years later, voters this November will once again have a chance to weigh in on the issue. The vote will test whether attitudes about affirmative action have changed over the past two decades.

Voters will decide Referendum 88, which aims to repeal I-1000, a pro-affirmative action initiative to the Legislature that majority Democrats passed in April in the waning hours of the 2019 legislative session.

I-1000 -- known as the Washington State Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Act -- would once again allow the use of affirmative action measures in state employment, contracting and public education. These measures could include outreach and recruitment to minority candidates, but not the use of quotas.

I-1000 also would prohibit preferential treatment, defined as using factors such as race or gender as the sole criteria for selecting a less qualified candidate over a more qualified candidate.

“All it does it makes sure that everybody has an opportunity to succeed in Washington state and that’s why I stand in strong support,” Democratic state Sen. Joe Nguyen said during the debate in the Washington Senate in April.

Sponsored

Specifically, I-1000 says the state can employ affirmative action policies in order to address underrepresentation of groups that have been shown through valid disparity studies or court rulings to constitute “disadvantaged groups.”

While proponents argue that I-1000 levels the playing field, opponents say it’s divisive and unnecessary.

During the same Senate debate in April, Republican state Sen. Sharon Brown urged a “no” vote as she spoke about the experiences of her daughters who are multiracial.

“My oldest daughter is in med school now and you know what … we checked no boxes and she got in and we are proud of it,” Brown said during the floor debate.

After the measure passed the Legislature largely along party lines, opponents staged an angry protest in the Capitol Rotunda. They chanted: “Vote them out … Let people out.”

Sponsored

The following day, opponents filed the referendum to repeal I-1000. Over the summer, they gathered enough voter signatures to qualify Referendum 88 to the November ballot.

One of the leaders of that effort is Linda Yang, who immigrated to the United States from China and worries that, under I-1000, Asian students will be denied admission to college in favor of other racial minorities.

“People know if we are allowed to use race as a factor, our kids are going to be discriminated (against),” Yang said in an interview, after filing Referendum 88.

Yang said immigrants arrive as outsiders with no political clout and that education is their only route to the middle class.

“We come here, we don’t have roots, we build everything from scratch, if we can do it, I think everybody can do it,” Yang said.

Sponsored

Opponents also dispute the idea that I-1000 disallows quotas – even though that language is explicitly in the initiative. They point to other I-1000 language that gives the state broad authority to remedy discrimination and allows for “participation goals” and “other measures designed to increase” diversity in public education, employment and contracting.

Proponents counter that I-1000 is needed to help address historic inequities. They also argue I-200 has done damage in the 20 years since it passed. For instance, they point to a state analysis that shows a steep drop in the percentage of state dollars spent with minority and women-owned businesses, from 13 percent in 1998 to about 3 percent in 2017.

Among the proponents are all three of Washington’s living former governors: Republican Dan Evans and Democrats Gary Locke and Chris Gregoire. Current Gov. Jay Inslee also supports the new law.

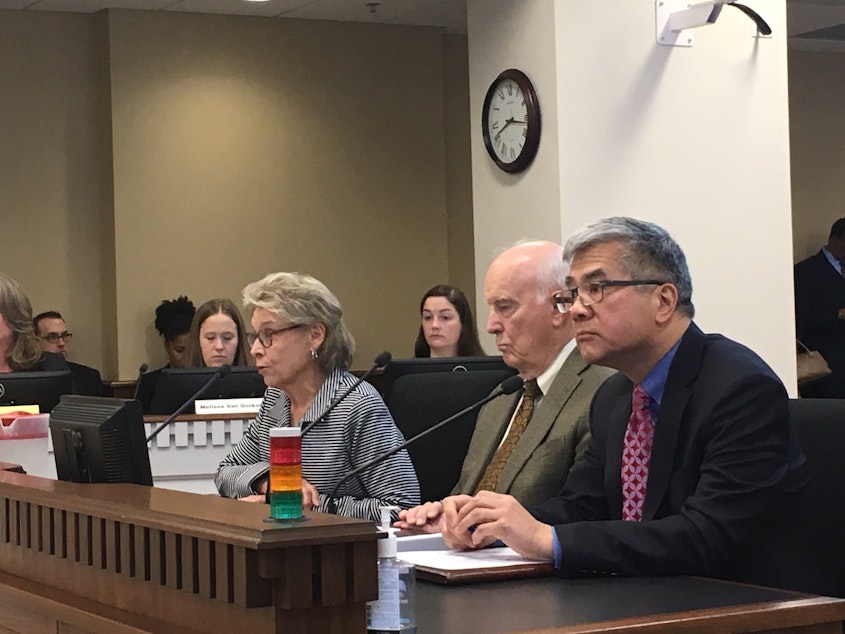

Testifying before a legislative panel in April, Locke, who was the first Chinese-American to be elected governor, emphasized that I-1000 is not a full repeal of I-200. He also said affirmative action had different connotations in 1998 than it does today. He said back then it was associated with set-asides, preferences and quotas.

“There’s no preferential treatment allowed under Initiative 1000, quotas are not allowed under Initiative 1000, the hiring and admission of unqualified or lesser qualified individuals is not allowed under Initiative 1000,” said Locke, who was a vocal opponent of I-200 in 1998.

Sponsored

Instead, said Locke, the goal of I-1000 is to make it clear to government agencies and universities that outreach and recruitment of women and minority candidates is OK.

Opponents respond that Washington’s public universities are more diverse, not less diverse, now than when I-200 passed. They also argue I-1000 will “inject” race into college admissions and state employment and create “different rules for different races.”

In addition to allowing affirmative action, I-1000 would create a governor’s commission on diversity equity and inclusion to monitor and enforce compliance with the law.

Besides current and former governors, I-1000 has garnered the support of several Indian tribes, as well as companies like Alaska Airlines, Amazon and Microsoft.

Opponents include former Republican gubernatorial candidate and radio talk show host John Carlson, who led the I-200 campaign in 1998. Among the donors to the “no” campaign is the American Civil Rights Coalition, led by Ward Connerly, a former University of California Regent who backed I-200 and similar efforts in other states to ban affirmative action from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s.

Sponsored

Even as the campaigns rev up, an unpaid $1.3 million debt from the I-1000 signature-gathering drive last November threatens to become a distraction.

Two signature-gathering firms who helped qualify the measure as an initiative to the Legislature filed a breach-of-contract lawsuit last month against the original campaign committee, the One Washington Equality Campaign, and a newly formed committee called the Washington Fairness Coalition.

The lawsuit seeks more than $1 million in damages.