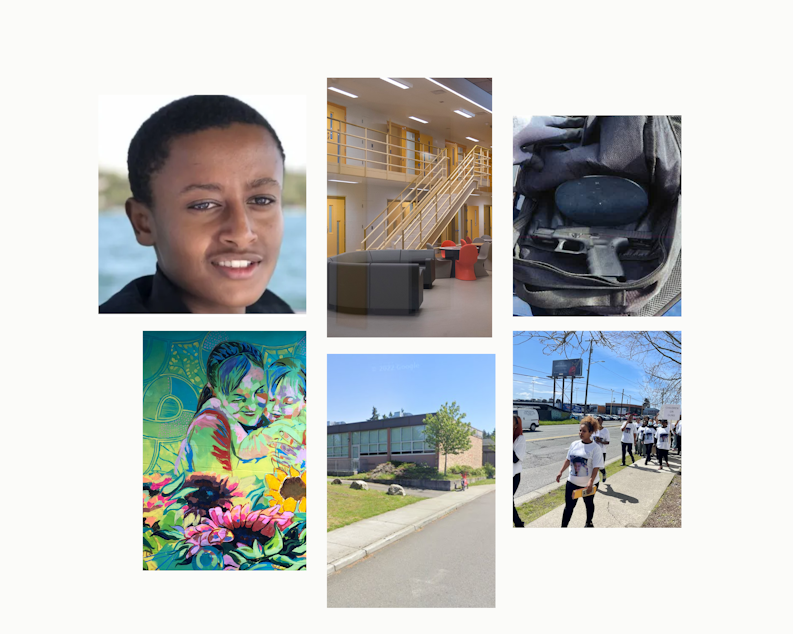

About the gun that killed a boy at Seattle’s Ingraham High School

This is the story of a gun.

It begins with a 14-year-old boy showing it off.

It ends with another boy dying in a high school hallway.

The gun is a Glock 32 that was manufactured in 2017. It is easy to control because it is light, with the feel of a two-pound weight when its 13 bullets are in the magazine.

It is all black, no frills, and moves through the recoil quickly. That means the shooter barely feels it when it discharges, allowing him to take aim again, and shoot again, even if he is a child. It is valued at $491.

The gun’s owner is a letter carrier for the U.S. Postal Service, a 39-year-old man named Mark who lives in Lynnwood, Washington, a suburb north of Seattle, in an apartment complex with his wife and children – and until last fall, the Glock, which he kept in a black belt bag in his bedroom closet.

***

Last October, a few days before Halloween, Mark called 911. The Glock was gone. He told police that he asked his wife and 14-year-old son if they’d seen it, and they said they had not. We are not including Mark’s last name because he has not been charged with a crime, nor is there talk that he might be, even though there could: Washington state requires that you lock up your gun if you live with children.

Sponsored

Mark’s son admitted later that he had lied and had, in fact, taken the gun.

It was 5 p.m. on a late summer day, or maybe early fall; accounts differ. He took the belt bag from his dad’s closet and walked down three flights of stairs to a secluded spot behind his apartment building, a narrow area with a railing that oversees a lush ravine. There, he opened the bag so his friends could see the gun.

In the small group was a 14-year-old boy, an aspiring rapper whose music showed promise. The boy asked if he could hold the gun, according to a police report, and Mark’s son relented. Then, allegedly, the boy sped off with the Glock to the Safeway next to the apartment complex, and to a waiting rideshare.

Mark’s son ran after him, shouting, according to witnesses, “Give it back!” and “Yo, bro, it’s not even my gun. It’s my dad’s.”

When Mark’s son reached the boy, the boy was stepping into the car.

Sponsored

The gun traveled from there. It was used, kids told police, to steal another kid’s black-and-white Panda Dunks, coveted Nike sneakers that are often out of stock. This was on the campus of another high school north of Seattle.

***

According to police reports, the Glock passed through at least four pairs of teenage hands by the time it entered Ingraham High School on November 8, 2022.

1: Mark’s son.

2: The aspiring rapper.

Sponsored

3: The aspiring rapper’s friend.

4: Finally, a 14-year-old boy with the initials TF.

On this Friday morning, the Glock was at Ingraham, but TF didn’t have it yet. He and two friends argued with upperclassmen in a school bathroom, where, according to attorneys, TF got punched in the face. Witnesses told police that one upperclassman, Ebenezer Haile, 17, wanted the gun.

As the boys emerged from the bathroom, Haile laughed at TF, a witness told police. Haile was overheard saying, “You’re not gonna bust it,” meaning, you’re not going to shoot.

But he did. TF pulled the gun from a backpack he was wearing and shot Haile, and then shot him again after Haile went down. TF, according to court records, shot at another student and missed.

Sponsored

Haile was taken away by medics, who pronounced him dead at 10:27 a.m. He’d been shot five times.

TF ran but was arrested later that afternoon with a friend.

When police found the gun, they remarked that the Glock’s slide was pulled back and locked in place.

“This condition of the firearm typically occurs when one discharges the firearm until they run out of ammo,” an officer wrote.

Sponsored

RELATED: 7 graphics that explain kids and guns in the Seattle area

A week later, a vice principal at a high school in a suburb north of Seattle called in a student about a different gun – a BB gun – and asked why she was posing with it in a video.

The student blurted out something unrelated: She knew about the gun used in the Ingraham High School shooting.

Police began investigating, tracing the gun back to Mark, who initially talked to officers but then stopped returning their calls. KUOW texted and called Mark and twice left letters at his front doorstep.

Mark responded Tuesday by text. “Sorry,” he wrote. “My lawyer said not to give any statement."

***

Teenagers aren’t allowed to buy guns by law. So how do they get them?

Of the guns in 54 open King County cases involving juveniles, 20 were stolen. That’s likely a low estimate, as police reports don’t say where half the guns came from.

Stolen guns are often used in crimes, which is why Seattle passed a law in 2018 requiring that all firearms be locked up. At the time, Mayor Jenny Durkan noted that stolen guns were fueling gun violence.

That same year, Washington state voters passed I-1639, a firearms law that says a gun owner could be charged with a gross misdemeanor for failing to secure a firearm if they “reasonably should have known that the firearm could be accessed by someone who is prohibited from possessing a firearm, such as a child.”

Gun owners who report a missing gun within five days may be off the hook if the gun was obtained during unlawful entry, which may or may not be the case here. Mark told police he noticed his gun missing a week and a half before he reported it stolen; his wife wrote in a statement that it had been missing for three weeks.

Renee Hopkins, of the Alliance for Gun Responsibility, which pushed the state initiative, said there have been “maybe three to five cases where they’ve been prosecuting really egregious cases.”

Hopkins continued, “It’s heartbreaking to think about prosecuting people in these often really tragic situations.”

Some of these cases involve parents who lost their children because their guns were within reach.

***

The father of the aspiring rapper, the 14-year-old boy who allegedly stole the gun from Mark’s son, said his son didn’t steal the Glock. The father asked that we use only his last name, Siu, to protect his son’s identity.

Siu said he has guns in his home, but that he locks them up, so his kids can’t access them.

“You kind of have to think like a kid,” Siu said. “I can’t leave the house and leave you alone with these guns loaded.”

Siu’s son was arrested three weeks after the Ingraham shooting. He was released hours later. Charges were forwarded to the Snohomish County Prosecutor’s Office, but Siu doesn’t know what, if anything, will come of that, as the case appears to have stagnated. His son was expelled from school and could not enroll elsewhere in Washington state.

“Maybe the kids didn’t make the best choices hanging out with certain people,” Siu said, “but now we have a child who has zero credits and lost the whole year of high school because of false accusations.”

In late April, nearly six months after he died, Ebenezer Haile’s family and friends rallied outside Ingraham High School.

When they arrived at the front of the school, their cries went silent to give Haile's mom, Tsedale Woldemariam, a moment. Emotion overtook her.

She hadn't been back to the north Seattle school since she dropped her son off that early November morning. An hour later, Haile was killed.

Woldemariam started to weep, bending over in pain as she held her younger son's hand. He, too, started to cry, and she pulled him into an embrace.

Mesfin Bulti, a pastor, said he had seen Haile at church, two days before he died. Bulti is a pastor at Life in Christ Ethiopian Evangelical Church in Lynnwood, where Haile’s family worshiped.

Bulti remembered Haile as a charming, loveable boy who made everyone laugh. He said Haile was always helpful and respectful.

Society needs to learn from his death, Bulti said.

“Losing him is heartbreaking for all of us, especially his mom,” Bulti said. “Schools must be free of guns. Kids need protection.”

Elrohi Shuge, Haile’s older cousin, said she spent every day last summer tutoring Haile.

“I’ve never wanted to see somebody succeed more than Ebenezer, because I knew the potential, and the mind he had was so bright,” she said.

A recent University of Washington graduate, Shuge said Haile’s death has inspired her to go on to law school and study public policy so that she can fight against gun violence.

TF remains at the King County youth jail. The King County prosecutor’s office wants to try him as an adult, which would mean an automatic 20 years, plus five because of the gun.

If he is tried in juvenile court, he would get out at age 21.

“My experience with kids in this position is that the first weeks or months are extremely hard,” said Sarah Wenzel, one of TF’s attorneys. “It’s very hard to appreciate the situation you’ve ended up in, and how drastically your life is changing — over frankly, something that probably happened in a matter of seconds.”

"He possessed the gun for literally minutes prior to the incident," said Adrien Leavitt, TF’s other attorney.

TF lived with his parents and a younger sibling and hadn’t been in legal trouble before, Leavitt said. He was on a special education plan.

“He’s just, like, the kid who is a part of his family,” Leavitt said. “He talks a lot about liking being a big brother. He’s never been apart from his family before this.”

Leavitt said TF was bullied through middle school. “That had a really big impact – on him and his family as well.”

We asked the attorneys if they dreamed of an alternate universe in which Mark had locked up the Glock.

“All the time,” Wenzel said. “If that gun had not made its way to that school that day, this would not have happened."

***

Today, the Glock is stored as evidence – inaccessible and locked up, as the law says it always should have been.

This story includes earlier reporting and writing by KUOW reporter Sami West.