Voice

This is a story about the way we make a statement.

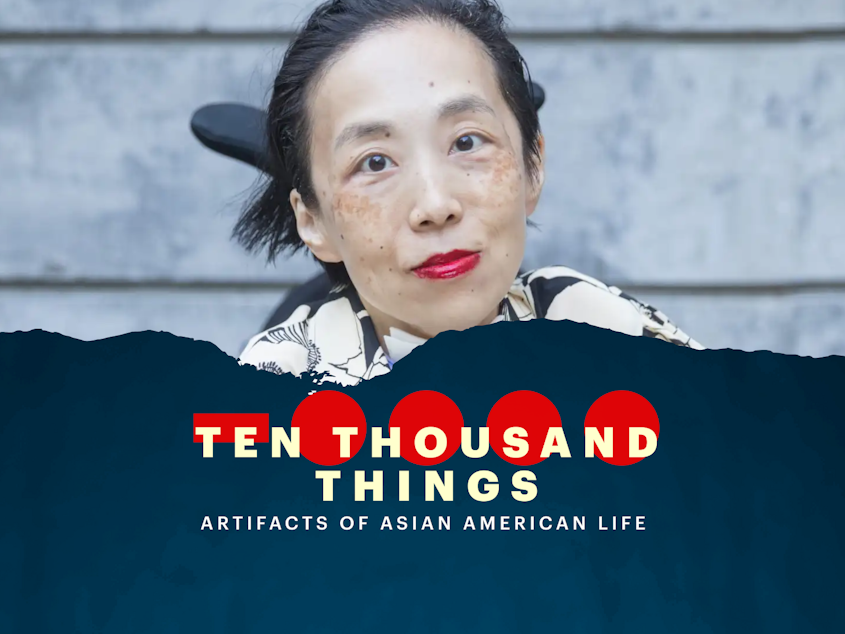

Alice Wong, a Chinese-American disability activist, came into her own as a public personality through creating and hosting a podcast on disabled voices. Her status as a person with a disability in an ableist world gave her access to a world of perspectives and voices that we don’t usually hear on public radio. And she prioritized putting disabled voices on the air. But losing her own voice and replacing it with an app forced her to reckon with a new relationship to voice.

Sponsored

Year of the Tiger by Alice Wong

Resistance and Hope: Crip Wisdom for the People, edited by Alice Wong

"Ten Thousand Things" is produced by KUOW in Seattle. Our host, writer, and creator is Shin Yu Pai. Whitney Henry-Lester produced this episode. Jim Gates is our editor. Tomo Nakayama wrote our theme music. Additional music in this episode by Jaylon Ashaun and Stan Forebee.

Search for "Ten Thousand Things" in your podcast app!

Partial funding of "Ten Thousand Things" was made possible by the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture Hope Corps Grant, a recovery funded program of the National Endowment for the Arts, plus support from The Windrose Fund.

Sponsored

And of course, we don't exist without listeners like you. Support "Ten Thousand Things" by donating to KUOW.

Transcript:

Shin Yu's Narration: A person who chooses the vocation of writing has a deep relationship to voice. Consider David Sedaris, who wrote Santaland Diaries, a humorous send-up of the author’s time working as a grumpy Christmas elf at a Macy’s Department store.

David Sedaris: The woman at Macy's asked, would you be interested in full-time elf or evening and weekend elf? I said, full-time elf. I'm a 33-year-old man applying for a job as an elf.

Shin Yu's Narration: But it’s also Sedaris’ physical voice - his distinctive nasal tone and high pitch - that makes him memorable.

Sponsored

His falsetto imitation of Billie Holiday singing Away in a Manger is burned into my memory.

Alongside the idiosyncratic voices of other public radio hosts - like Sarah Vowell...

whose voice has been likened to that of a boy soprano on the verge of cracking.

Sarah Vowell: There comes a time in the middle of any halfway decent liberal arts major's college career when she no longer has any idea what she believes.

Shin Yu's Narration: or Starlee Kine,

Sponsored

Starlee Kine: Before I explain why I decided to write and record a breakup song

Shin Yu's Narration: whose twee voice slips into occasional vocal fry.,

Starlee Kine: even though I have no musical ability and can't play an instrument of any kind, I should probably explain a bit about the breakup itself.

Shin Yu's Narration: These voices, which are anything but typical, pull the listener's ear along. And though you might resist or even recoil at first listen, the next you thing know, you've been seduced into sitting through a long, bizarre yarn.

Their unusual voices made these radio hosts into public radio darlings.

Sponsored

Our voices communicate our gender, our age, our vulnerabilities, even our personality. No matter whether or not we like the sound of our voice, voice is deeply identified with who we are. So when a public personality actually loses their voice, what happens to that sense of self? How does a person recover from that loss?

Alice Wong is a Chinese-American writer and podcaster who confronted these issues head on. During the pandemic, Alice had several medical crises that led to a 4-week stay in the ICU. She was discharged with a tracheostomy, a tube inside her throat attached to a ventilator that allows her to breathe. She can no longer talk with her natural voice. So instead..

Alice Wong: I use an app on my iPhone and laptop called Proloquo4Text. It is a text to speech app that I started using last summer after losing my voice due to a tracheostomy.

I use it every day from the moment I wake up. Aside from gestures and making sounds with my hands, this is my main mode of communication, so I use it often the entire day.

Shin Yu Narration: Welcome to Ten Thousand Things, a podcast about modern-day artifacts of Asian American life

I’m your host, Shin Yu Pai. Today, the voice.

Alice Wong is widely known as a disability rights activist. Alice graduated from the University of California San Francisco, where she later worked conducting research and trainings on personal care services that help those with disabilities live in the community instead of institutional settings.

Alice used her voice to lobby for her university to include disability-related curriculum as part of their cultural competency courses. And this catapulted her to national recognition. In 2013, President Obama appointed Alice to the National Council on Disability. In a role that allowed her to advise the U.S. government on policies, programs, and practices that affect people with disabilities.

Alice started a podcast called Disability Visibility in 2017, in partnership with StoryCorps.

Alice Wong: I was a fan of StoryCorps, which was on NPR's Morning Edition every Friday. Hearing those amazing stories got me thinking about the importance of oral histories, which led me to forming the Disability Visibility Project.

Shin Yu's Narration: Her podcast featured conversations on politics, culture, and media with disabled people and put disabled voices on the radio.

Alice grew her skills in audio storytelling as a fellow at Making Contact Radio, a radio non-profit based in Oakland, California.

Alice Wong: Learning the basics of recording, editing, and radio terminology gave me more confidence that this is something I could do. I got to co-produce and write my first radio story, and I knew this was a medium I wanted to explore further.

Shin Yu's Narration: As part of her fellowship, she wrote an article calling out the need for more diverse disabled voices in audio. She hoped it would start a conversation with the radio and podcasting communities. In her piece, she called for more disabled voices on the radio. People who lisp, stutter, gurgle, stammer, wheeze, salivate and drool. She wanted to hear voices that communicate, enunciate, and pronounce differently. And people who use ventilators or other assistive technology, including computer-generated speech.

Alice wanted to disrupt the normalcy of the default straight white male public radio voice. To challenge listeners to concentrate and listen more deeply. And the response she got?

Alice Wong: Not a single person reached out in response to this piece.

But oh, well what can you do? I was a newbie and no one in radio, was going to listen to me, pun intended. Haha. And now more than ever, people are doing their own thing, which is what I did. Much like every industry, radio has a huge diversity problem, and the editors and producers who decide what stories matter, who gets to tell those stories? And how those stories sound still adhere to white, middle class heteronormative standards

Shin Yu's Narration: So Alice started her own podcast. She created Disability Visibility Project and produced her show for four years. She interviewed guests like disability rights activist Judith Heumann, Seattle author and media critic Elsa Sjunneson, and Andrew Pulrang, one of the co-organizers of Crip the Vote.

Alice Wong: As a first time podcaster, my voice wasn't smooth or easily understandable..

The rhythms of my speech were not natural and interrupted by breaths of air taken by the machine. So there were moments of pauses during the conversation, but I grew to embrace this difference, this uniqueness,

Ideas of what is considered a good voice gatekeep marginalized people, making them feel they can't take up space and sound. And the reality is there is space and sound for all of us.

Shin Yu's Narration: As a member of the disability community, Alice had a unique lived experience that allowed her to be in deep conversation with her guests. Alice was born with spinal muscular atrophy, a condition where certain nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord break down, causing progressive weakness and atrophy in the muscles in the trunk of the body. She stopped walking around the age of seven or eight and transitioned to using a walker to a manual wheelchair to an electric wheelchair to a customized wheelchair. Her lung function has steadily declined throughout the decades because of a weakening diaphragm. A key muscle used in singing, public speaking, and deep breathing. So as an adult, Alice started to use an assistive device called a BiPAP to help her breathe.

Alice Wong: In my thirties, I started using a nasal mask that's attached to my bi pep machine, a noninvasive, a ventilator. I had to adjust to sounding differently as my voice sounded a bit foggy. I remember being very self-conscious about it at first.

Shin Yu's Narration: As Alice got used to the Bi-PAP , she noticed a difference in the way people related to her. Often, she had to repeat herself to make herself understood. If a breath arrived in the middle of a phrase, she had to pause. Causing awkward speech patterns. Talking for long periods of time while using her mask caused Alice to salivate a lot. She needed to pause to swallow. She found herself having to suppress the embarrassment she felt around her vocal difference.

Alice Wong: Eventually, I adjusted to this new way of life and I embraced it as part of my disabled cyborg body. I think of it now as I am adjusting to not being able to speak at all. I'm eventually going to be okay and figure shit out.

Shin Yu's Narration: Alice stopped producing the Disability Visibility podcast in 2021, after making her 100th episode. She landed a book deal and found other ways to circulate the stories from her community, as well as her own stories. Just as she was preparing to publish a collection of her personal essays and launch that book into the world, she suffered a medical crisis which resulted in a collapsed lung. Alice now lives with a tracheostomy that’s connected to a ventilator. She no longer has the ability to speak.

Alice Wong: It's hard because I am forced to slow down, type my responses, and be more intentional when I speak using the app.

Shin Yu's Narration: The text to speech technology that Alice uses allows her to have a voice. And that voice has an identity and name too.

Alice Wong: You can select from a number of voices by gender and accent by country. I honestly didn't like any of them. None of them felt like me, but I resorted to the voice called Heather, a female voice with an American accent that you are hearing now.

Shin Yu's Narration: Heather replicates human speech for Alice, but there's still an awkwardness to the conversation.

Alice Wong: People have to wait before they can reply, and this can be an atypical experience, but I am lucky to be able to type with relative ease and to have access to this technology. I try to remind myself of this whenever I am frustrated and impatient.

Shin Yu's Narration: Alice has found herself missing her physical voice. It was a part of herself that she loved.

Alice Wong: It was such an expression of my snarkiness, bitchiness humor. My razor sharp wit comes out clearly and quickly through my speech. Alas, I cannot do this anymore, although if people look at me, they'll see my facial expressions and know exactly what I'm feeling, but it's still not the same.

Shin Yu's Narration: Still, Alice’s physical expressions and actions ensure that she’s heard and seen. Even if she can’t speak, she takes up space. She makes her presence known.

Alice Wong: I bang things on my desk, gesture with my hands, smack my lips, make clicking sounds with my mouth, or rock my head back and forth to get someone's attention. I set my phone to the highest volume to make myself heard.

Shin Yu's Narration: Despite her loss of speech, Alice has still found ways to activate her voice and to experiment with voicing.

Alice Wong: Last fall I was approached by someone from Raw Materials, a podcast by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art to remix several of my previous episodes featuring disabled artists.. Every season they feature a different podcaster, and this was an opportunity I couldn't pass up.

Interviews like this are also attempts to be in this space with some modifications, such as requesting questions ahead of time so I can type my responses and record them. Some people may not consider it a typical conversation, but this is what works for me now, and I am a constant work in progress.

My voice is making a statement in itself and that I still have a lot to say with.

Shin Yu's Narration: What I've admired about the many voices of Alice Wong are the ways in which she's used the voice as a tool of resistance. Whether on the page or behind the mic. While I haven't had to confront the specific struggle of losing my physical voice, I'm very familiar with the journey towards finding and claiming an authentic voice. Using one's voice to say something true.

As host of this podcast, I rely on my physical voice to express what I have to say. But before making podcasts, I was a poet. I explored my voice and identity on the written page where I learned to coax emotion out of an audience. Without having to necessarily embody emotion in my speaking voice. I became skilled at hiding, removing myself from my poems. By writing from a third person perspective. Or by being abstract. And then I started making silent poetry films, where my physical voice wasn't present at all. And this felt fine for a time, because it's not always easy or welcome to have an Asian American perspective in the world. But even silence makes a statement.

Writing for Ten Thousand Things is different. In part, because these are real stories from my community and from my own lived experiences. I can’t get away with hiding behind the words or burying the narrative. My editor Jim reminds me of this every time we tape. The ideal voice is not the accessible, chatty voice that we associate with public radio nor someone else’s notion of neutral voice, or the boy next door, who I could never emulate or embody anyways. Authentic voice is something much harder to pin down. This is the voice of my true self, with upspeak, so like um occasional verbal fillers, and all.