Name

When we come into this world we are given a name. It is etched in ink on our birth certificate, pasted onto our cubbies in pre-school, and signed onto paper to acknowledge our union with a beloved. A name has power.

A name is an object that defines who we are. But what if our name is wrong? Poet, educator, and cultural worker Ebo Barton tells us a story about the power of names and their journey to change their name and reclaim their true identity.

This episode of Ten Thousand Things won a 2023 Golden Crane Award for LGBTQ+ storytelling from the Asian American Podcasters Association.

Ten Thousand Things is produced by KUOW in Seattle. Our host, writer, and creator is Shin Yu Pai. Whitney Henry-Lester produced this episode. Jim Gates is our editor. Tomo Nakayama wrote our theme music. Additional music in this episode by coldbrew, Jaylon Ashaun, and Gracie and Rachel.

Search for Ten Thousand Things in your podcast app!

Partial funding of Ten Thousand Things was made possible by the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture Hope Corps Grant, a recovery funded program of the National Endowment for the Arts, plus support from The Windrose Fund.

And of course, we don't exist without listeners like you. Support Ten Thousand Things by donating to KUOW.

Related Links:

Ebo Barton performs Freedom, Cut Me Loose

Sponsored

Transcript

Sponsored

Shin Yu Narration: Hi there, I’m Shin Yu Pai. Welcome to the second season of our show...now with a new name.

The Blue Suit was what we called the first series of this show. I was inspired by New Jersey congressman Andy Kim's legendary blue J. Crew suit, now in the Smithsonian. We did a whole episode about it, and if you haven’t heard it you should check it out.

But now our show is evolving. Because in the Buddhist sense of change, nothing stays the same. Our new name is Ten Thousand Things. "In many Chinese sayings and in classical poetry, the number “ten thousand” is used in a lyrical sense to convey something infinite, vast, and unfathomable. I think– the story of Asians in America is just that.

Our focus will still be on objects: modern day artifacts that tell the stories of being Asian in America. Objects like a bicycle or book or things a little less tangible, but just as real like a name.

A name is a thing that is changeable.

Sponsored

Ebo: My name is Ebo Barton,

Shin Yu Narration: People, young and old, take new names for many reasons. Among them: Marriage. Immigration. And to make a name easier to say for those who can't pronounce it.

Ebo: Ebo Gemilla Graham Barton.

Shin Yu Narration: You may have a special Burning Man moniker, or a name from hiking the Pacific Crest Trail. Or a name given to you in the military.

There are spiritual reasons for name changes - like receiving a special name from a teacher. Or a missonary. And then there's also Good fortune.

Sponsored

In my own extended family and culture, many of my female cousins altered their given names by adding or removing a single stroke to the Chinese character depicting their name, to mitigate the bad luck that plagued them. This cultural practice is called the rectification of names.

Ebo: by day I am the director of housing services at a nonprofit called Lavender Rights Project.

Shin Yu Narration: Other times, a name may just feel like it doesn't fit.

So we take on a nickname that our closest friends may know us by. or a pen name - like a nom de plume by which we are known in public. But that's a lot of names and identities to manage.

Ebo: And by any other time, I'm a poet and cultural worker in Seattle.

Sponsored

Shin Yu Narration: Some of us make the choice to make a name change official. Shed what doesn't fit. What we are called can become a "dead name" - something that is retired, as if the identity that went with that name has moved on and beyond. To a distant shore.

Ebo: So as a transgender person, I came out in public, and my journey has been documented in that way because of how public I've been about all of my identities. Um, so it kind of gives me this privilege to be able to change my name publicly as well with no shame. Um, but I think that a. transgender folks, don't have that same privilege. cuz we just don't live in a world where it's safe to do that yet.

like, we don't all get to talk about the journey with our name. expose what our names used to be or what we were given. it's just, it's really cool that I get to talk about it.

Shin Yu: This is Ten Thousand Things. A podcast about artifacts of Asian American life.

Shin Yu Narration: I'm Shin Yu Pai, your host. Today, a name.

Ebo Barton never identified with the name that their mother gave to them.

Ebo: My mother named me, Carmella Lynn. and

You know, I've always sort of hated this name.

I never felt this name was mine.

Shin Yu Narration: They tried to cut it down to a shorter version and to change it entirely.

Ebo: I remember telling a second grade teacher that I wanted to change my name to Paula. Carmela is no longer my name. I want you to call me Paula. And you know, my teacher's not really understanding what's happening. Called my mom. And my mom asked me like, did you say this? And I was like, yeah, I just don't want it anymore.

Shin Yu Narration: Paula didn't stick. So Ebo tried out a handful of other names to see what resonated and felt right to their ear and imagination.

Ebo: I noticed that a lot of people in my life, Cut their names down to like the first part of their names. And so I was like, oh, well I can be car. And then in my child brain, I was like, well, that's not interesting enough. I wanna be motor home. And so I told people to start calling me motor home for some reason. And so it was this constant like feeling of this name that just I could not figure out.

Shin Yu Narration: In choosing our names, our parents come with the best of intentions. Some spend months looking at long lists of baby names. My husband and I went back and forth for months over the symbolism and qualities behind each potential moniker, when thinking about how we'd name baby Pai-Bergman. I wanted to name our son after a favorite artist like Cole Porter or Lucien Freud.

Ebo: Carmella was, it was the character. That one of her favorite Filipino actresses played. It was a villain. And I think that I've always hated this story, why would you name me after the villain?

Shin Yu: I also have a birth name, which I don't go by, and my father named me after an American actress and celebrity Doris Day.

Ebo: Oh yeah.

Shin Yu: It's interesting that, Carmella was this, Villain, my father gravitated to Doris Day because she was like this, you know, kind of

Ebo: Mm-hmm. , Hmm.

Shin Yu: like all American kind of thing. And, and just, uh, you know, like, kind of what they gravitated towards or saw as kind of cultural icons is really interesting to me.

Ebo: really interesting. And yeah, like, and I also wonder if it's the character that they played that inspired the name or is it the homage to the actual person?

Shin Yu: Sure. Yeah. can we ever know?

Ebo: Right, exactly.

Shin Yu Narration: To their family, they were Ela, an abbreviated version of Carmela.

Ebo: I definitely tried to identify with it more just because it wasn't that full weight of the name. And then Ella even with the a sound at the end of it, it, for me, it felt gender neutral.

I felt more comfortable in my skin with that version.

Shin Yu Narration: A name is one outward marker of an identity. Other markers of Ebo's identity also telegraphed complexity. Ebo is a trans-masculine non-binary person. And they're Filipino and Black.

Ebo: I've brought a lot of, Filipino culture to my black identity, but I also think that I've brought a lot of my black identity to my Filipino side.

Shin Yu Narration: Being mixed race isn't easy as a kid. Mixed race children may not always see the world reflected back to them. Ebo struggled with being enough just the way that they were. They were viewed as the Black kid by the Filipino side of their family, and as the Filipino kid to the Black side of their family.

Ebo: I think that there, there's a lot of anti-blackness in Filipino communities that were. Not ready to stand up to. I think a lot of our communities are, especially in current times, but as I was growing up, that was not a factor because of this desire to assimilate into American white culture.

Shin Yu Narration: Ebo felt conscious of having to perform their identity. Prove that they belonged to the culture.

Ebo: I often had to exceed the expectations of Filipino in order to prove my Filipinoness because I was mixed race.

I remember being in Disneyland and a Filipino family was behind us, and me and my sister had, braids in our hair. And they were talking in Tagalog about us.

Talking about, you know, when they have hair like that, they don't, shower and, kept saying all of these terrible, terrible things and without thinking, because this is also my language, . I turned around, I'm eight years old. I turn around. Yeah, it's not true. No, you're not.

And it was just a shame that they felt obviously, and they left the line. But oftentimes it was not as easy as explaining that to folks. That was definitely a, a scarring moment for all of us where it was just like, oh. Even, you know, like even if we speak the language, you're still not seeing us for who we are.

Shin Yu Narration: Ebo's relationship with language became a place for deep liberation. Ebo found creative writing. And through diving into the written and spoken word, they were able to explore their identity. Speak it aloud and into being. Like an act of magic or conjuring.

Ebo: I was the youngest in my family. Very confused about race , and ethnicity and identity and gender, um, and writing. What I discovered was, if I made it sound pretty enough, everyone wanted to listen to me.

Shin Yu Narration: But literature classes didn't provide the models that Ebo needed to stretch their imagination fully.

Shin Yu: In high school, , I wasn't really exposed to a lot of poetry in the classroom except from, you know, old dead white guys that I didn't care about so I thought that I invented spoken word, um, when I was like 14, and I was like, no, my, my poetry's different. It needs to be said out loud. it was this idea that I did wanna share because this poetry had to be read out loud. I just didn't have the resources or access to do that.

Shin Yu Narration: An identity is created over time. You may think you have a handle on who you are. But that person evolves. as a young person, Ebo connected more with their Asian side - through food, language, and family. But that changed when Ebo left home and joined the military, where they were seen as solely Black.

Ebo: You were either black or white in the Navy, in my opinion. And so that's when I, had to figure out like what this was and how it works out. And depending on what environment I'm in, like who am I gonna identify with or how will someone perceive my identity?

Shin Yu Narration: Not having to think about how we're perceived or seen is not a right afforded to everyone. Ebo was aware from a very young age of stereotypes and judgments directed towards them. And these misperceptions showed up everywhere - from the magical kingdom of Disneyland to the U.S. Navy.

Ebo: so I was in the Navy during the don't ask, don't tell. A lot of parts of my LGBTQ identity were hidden because I just didn't want to deal with whatever was gonna come.

That particular policy wasn't enforced across the board in the same way and with the same people. And so there was always this fear of, I could be the example that they set, so I'm just not gonna. engage with that part of my life at all. So it's sort of this removing the titles, removing the, you know, the mask of all these things that I am so that I can just be, serving the country.

Shin Yu: Was that hard to shut down those parts? Yeah,

Ebo: Absolutely. I was, uh, a machine that just did this thing every day. And that I was not who I, who I am. All these different expansive ways that I could exist. Yeah..

Shin Yu Narration: But while Ebo struggled to feel at home in their skin and in their name,

They found something else - a place to belong. They found the Seattle Poetry Slam scene .

Ebo: Back then it was in the Fremont neighborhood and I showed up and it was this whole magical community of writers that wanted to know what you were doing and how you were doing it, and you know, like conversing with each other about their next work.

Shin Yu: Were there other poets of color in that group?

Ebo: Yeah, very much so. And they were excited to see me, which was also the, the like most excited, cuz usually I feel like in, in predominantly white spaces, we become each other's competition. Um, and so I walked in and it was immediately like, who are you? What's your name? Like, hang out with us,

Shin Yu Narration: A shared love of words evolved into a a community of like-minded people. A community that surrounded and supported Ebo in their creative self.

At the age of 32, Ebo came out as a non-binary person. They came out during their show called "How to Love This Queer Body of Color: An Unapology". This new recognition of self made the name Ela feel even more like a misfit.

Ebo: Um, and so I wanted to change it so badly, but what I did discover during that time was that E sound felt like it was mine.

Shin Yu Narration: They started intuitively to look up names that started with an E sound.

Ebo: Uh, Ebo immediately showed up .

Shin Yu Narration: The significance of this name was both mythic and mystical. The Igbo people are an ethnic group in Nigeria, or central West Africa. On St. Simons Island, in Glynn County Georgia, A group of Igbo captives revolted against their white enslavers. At a place that is now known as Ebo's landing.

Ebo: The myth is that, they killed all their captors and turned into birds and flew back home rather than being captive. The real story is that there was a mass suicide of these folks. But they did kill their captors. But the idea is that they would rather die than be put in captivity. And I thought that was such a powerful story.

I took to that story.

Shin Yu Narration: There was another meaning. Ebo discovered the name also means a child born on Tuesday. Which they were.

Ebo: And so I immediately, I was like, well, this is, this is my name.

Shin Yu Narration: Ebo had found their name. It was time to start trying it out.

Ebo: Um, I started, uh, using. my name at Starbucks to be Ebo to see how it felt to answer to it.

Like, what does it feel like? Does it still feel like mine? And it totally did.

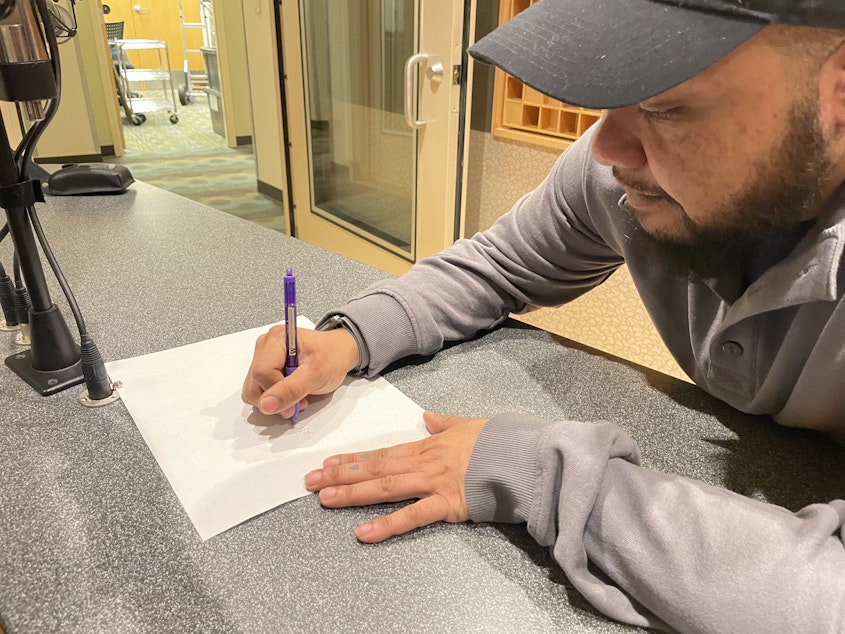

Shin Yu Narration: Ebo's confidence grew and they decided to put their new name into the world. How? Facebook, of course. Ebo posted a note to their wall that their friends would see and read

Ebo: I was, uh, really, really, really scared, to post it and, because I remember like typing it and then erasing it and then typing it and erasing it

And it was like, Hey, um, you used to know me as Ella. I'm thinking about being Ebo and, I wanna change my name or change my pronouns to they, them pronouns. I would really appreciate it if you would try to do this.

Shin Yu Narration: The timid post was received well. Friends showed support.

Ebo: My friend Greg was like, cool, Ebo, they, them got it.

Shin Yu Narration: But Ebo's family struggled most with accepting and adapting to the change. There was complex grief to work through.

Ebo: There is somewhat of a grief that happens with family members that doesn't happen with other people. I think my mom is still grieving the daughter that she thought she had. I try my best to be understanding of it, but sometimes it does hurt when the rest of the world has now Got it.

Shin Yu Narration: The resistance felt somewhat surprising. Tagalog, their mom's native language, doesn’t actually use gendered pronouns

Ebo: So the pronoun in Tagalog is Sha and it's not gendered at all.

Shin Yu: That's like Chinese. Yeah, yeah.

Ebo: very not gendered. Everybody's that, right. She heard. Yeah, she heard they him. And so, um, I think that always confused me. of like, what was the barrier for her, to change? Because I was like, well, in, in Tagalog it's, there is no gender, so what would be the difference?

Shin Yu Narration: Even more puzzling was that Ebo's Mom had no problem relating to a transgender woman in the Philippines. As a young person, Ebo had traveled back home with their mom. Ebo remembered seeing this stranger perform.

Ebo: There was this trans woman who was performing and she sang this beautiful song on the piano and everybody was just so enamored with her. Even my mom went over to. You know, I, I, I, what I say is that to go b a femme with her. And so they were talking about each other's nails and complimenting each other's outfits and things I never did with my mother, right? Like I was not that type of girl when, when I had to live that life . And so it was just so interesting and, and there was also this heartbreak of like, what is different when we cross the ocean?

Is it the safety that you're like, am I now unsafe because I say this in America versus in the Philippines? Or is it because you can identify with the femininity?

Shin Yu: Mm-hmm. . Yeah. That's so complex.

Ebo: Yeah. I think I, I often have these like questions that I keep, um, as to, not, as, to not be angry about it. Cuz I think that, you know, especially with a mother's perspective, like I just, there's just no way I can understand that.

Shin Yu Narration: For myself, my father and mother still slip and call me by my birth name from time to time. My mom has always misgendered me. For a long time, I thought she just confused me with my brother, but it's likely that she wasn't used to gender-specific pronouns because English just wasn't her first language.

There is a gap between who I was to my parents and who I have become. The name Doris meant something to them. and though the name never resonated for me - it's ancient origins do. For the Grecians:, Doris means "gift."

But just because you resonate with the symbolism of a thing, doesn't mean that you want to be called that everyday.

For Ebo, their chosen name stuck. And there came a time when they were ready to take it public.

Ebo curated and directed their first major production. A spoken word showcase that centered poetry on the strength and resiliency of queer people of color. Their show, How to Love this Queer Body of Color: An Unapology was coming to an end. It was the last night. And it was the biggest audience of the two week run. And the MC stepped in front of the mic and welcomed Ebo Barton to the stage.

Ebo: and there was this sort of like, do is, do I go up there now ? I did, and it was okay and no one died. I didn't burst into flames and everything worked out and, the applause happened, all of the things.

And so there was this natural transition of. This is my name now.

Shin Yu: Well, what do you felt like began to shift or change for you when you started using this name? Ebo Barton.

Ebo: Wow. Um, yeah, like that's, that's such an interesting question, like, because I feel like I was granted a piece of confidence that I never got before because I get to be Ebo , right? Like, I just, and it, so it was just this authentic feeling of like, okay, so now I get to just be myself. Like, what does that mean to be yourself when you've, you haven't been for so long?

But definitely I feel like something happened for me on stage, uh, being more comfortable in my skin, uh, and not feeling like I was hiding behind anything.

Hi, I'm Ella. You know, like, and that felt like this, uh, even now it feels like a stranger, like I'm saying, a stranger's name. It doesn't feel like it was ever mine. And so I think that, yeah, I was like almost like putting on a mask when I said it to someone.

And now, you know, I'm taking it off every time I say, Hey, my name is Ebo. Or, you know, like, or introduce myself. Um, you know, I said it in a video, like I was recording a video today and I was like, hi, I'm Ebo. And like, I was like, I am Ebo . So, um, so now it's starting to feel like mine. It's starting to feel like skin now in which Ela didn't like, never really did, but now it's not the, it's not the weight on me.

Shin Yu Narration: The support of the audience and their community gave Ebo the motivation to keep moving forward. So they updated their website, email, social media handles and legal documents

Ebo: I changed it all. and I think that there was also, part of me didn't wanna let go of that email either. Uh, so I was definitely forwarding, you know, doing the forwarding inbox for a while.

Shin Yu: Do you continue to do that? No. Or has it fully retired?

Ebo: I fully let it go. It's gone. ? Yeah. Wow. I don't even remember the password anymore, so it's gone

Shin Yu Narration: It's not so hard to change an email or an account setting . But The real hurdle? Getting through government bureacracy!

Ebo: Social Security wants you to have a driver's license first, and driver's license wants you to have your Social Security first. But it doesn't seem those two agencies are talking to each other, . Um, and then, you know, all the different fees and the navigation of all of those.

But, what's interesting is that the easiest part for me, which made me rethink about what great decisions I made in community was, changing my name with people, my interpersonal relationships was the easiest part. Um, and I feel really lucky for that is that there was not much of a stumble for most of the people in my life.

Shin Yu Narration: A name is a thing that is changeable. A piece of paper. A public persona. These things are maleable. The name that we choose can brightly light the path to the life that we want.

Taking a new name can be deeply karmic. When I gave up the name Doris in my 20s, like Ebo - I'd spent decades feeling a profound disconnect from my namesake and origins. I had been the opposite of all-American. When I started using the name Shin Yu which my 3rd uncle divined for me weeks after I was born - I started a process of becoming. Roughly translated, my Chinese name means happy treasure, or said more poetically "optimistic jewel." It's important to note that I have strong pessimistic tendencies. A more fitting name might have been "pessimistic lump of coal."

But I liken Shin Yu to a dharma name. I have one of those too. Given to me by a Buddhist master, my spiritual name translates as "liberatress of the Buddha." What was given to me was a name that takes some growing into. And living up to.

When we put aside something that no longer fits us, we make room for new selves and new futures for those visions of a more actualized self.

Over time, the name molds around us to become a central part of who we decided to be.

Now, when that post comes up on Facebook memories, Ebo can feel how far they have come

Ebo: What I noticed the most of how, how, how passive I was before of uh, sort of passing this closed note to someone with my new name and pronouns. And now there is definitely, you will call me Ebo. You will you say them or he him pronouns.