With rulings against racial bias, WA Supreme Court starts 'hard discussions'

Over the past five years, the Washington Supreme Court has issued a series of rulings aimed at combating a fraught problem within the legal system — implicit racial bias.

The court has relied on a new legal test: whether an “objective observer” could see racial bias as a factor in who gets to serve on juries, who gets convicted, and who wins in court.

Skeptics say these decisions have left confusion and uncertainty in their wake, while supporters say these decisions are a long time coming.

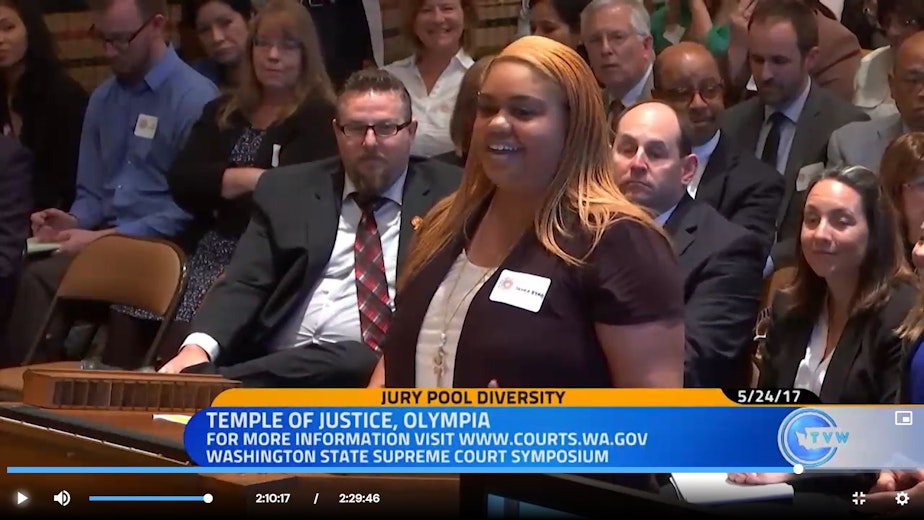

In 2017, a young mother and college student from Seattle named Ausha Byng stood before the Washington Supreme Court at a symposium on jury pool diversity. Byng, who is Black, said she’d been excited to get a jury summons. But she said she was dismissed, after answering that she didn’t trust police officers.

“During the questioning, one of the lawyers asked me specifically if I would be able to put my feelings aside about the police. My answer was yes – I absolutely wanted to be there, I wanted to be on the jury, I wanted to try the case,” Byng said.

The following year, the Washington Supreme Court adopted a new rule created by attorneys for the ACLU of Washington. It requires more scrutiny before people of color can be dismissed from a jury pool.

Chief Justice Steven González said in an interview last month that the change was based on the court’s conclusion that ”people of color were being systemically – systemically—removed from jury service and that there was a need to stop it.”

Sponsored

Previously, González said, people of color could be dismissed as long as attorneys cited a reason other than the person’s race. In Byng’s case, the prosecutor might have said it was because she didn’t trust the police. González said this new rule, entitled GR 37, requires the court to pause and look closely at whether race could be playing a role.

González said the rule states, “If an objective observer, defined as someone who is aware of the history of bias in our nation, could conclude that race was a factor, then that juror may not be removed.” Under this new test, a juror like Byng might have been retained.

And the court hasn’t stopped there.

Using the “objective observer” test, the court has struck down an array of lower court decisions over racial bias — not just in jury selection, but in verdicts in criminal and civil cases.

Sponsored

Pierce County Prosecutor Mary Robnett said, “It’s clear the supreme court has taken very seriously its role in trying to address disparities and bias.” She called the new “objective observer” rule for jury selection the court’s most significant change in the last decade.

In the case State v. Sum, which originated in Pierce County, the court said the subject’s race must also be considered in determining the legality of police stops.

Robnett said additional cases will provide more clarity over time. But in the meantime, she said these decisions have left prosecutors and police feeling uncertain about how to do their jobs.

“Often, police officers perform best if there are sort of bright-line understandings about what is permissible and what is impermissible in terms of how they conduct themselves and how they police their communities,” she said. “So a decision like Sum really blurs a lot of those bright lines and I think leaves a lot of uncertainty.”

Sponsored

She added, “Our deputy prosecutors are probably a little bit like police officers, wondering what is okay now and what is not okay. And we’re doing our level best now to follow the law.”

Last fall, the Washington Supreme Court extended the new “objective observer” standard to civil cases. In the case of Henderson v. Thompson, a Black female plaintiff sued for damages after a white female driver rear-ended her car. In describing the plaintiff as “combative,” the court said defense lawyers evoked harmful racial stereotypes.

Justice Raquel Montoya-Lewis wrote for the majority, "During the trial, Thompson’s defense team attacked the credibility of Henderson and her counsel— also a Black woman — in language that called on racist tropes and suggested impropriety between Henderson and her Black witnesses."

The court found that an objective observer could conclude that racial bias was a factor in the jury’s final award, and ordered the lower court to consider a new trial. It further stated that the prevailing party had the burden of proving racism was not a factor in the verdict.

Robnett said the Henderson decision seems to prohibit some established legal tactics used in cross-examination, based on the race of the different parties in the case. “It seemed to me in reading Henderson that they were disfavoring or prohibiting some kind of standard legal arguments – like that the plaintiff might have a financial motive to embellish their injury,” she said.

Sponsored

The decision has been blasted in conservative media as unworkable. But supporters call the court’s efforts to address racial bias “revolutionary,” and say other states are poised to follow.

Robert Chang is a law professor and executive director of the Korematsu Center for Law and Equality at Seattle University. He said the court’s expansion of the “objective observer” standard is an important new strategy to address implicit racial bias throughout the court system.

Chang said, “It’s fascinating to see how the court has said, ‘Well, if this is a standard that makes sense in this context, with the exercise of peremptory challenges [of jurors], might it apply in other circumstances?’”

He added, “The idea here is if we allow proceedings where race played an improper role to continue, that person is not receiving fair treatment — that person is not receiving due process. So what do you do? You go back and they get to do it again, with due process.”

Sponsored

Chang said the California State Legislature already adopted Washington’s new “objective observer” test for jury selection. He’s hoping they’ll use it to look at questions of implicit bias in other settings, as Washington has done.

“I’ve been talking with advocates in California about the other ways that the ‘objective observer’ has been extended to address other areas of discrimination that operate in the criminal trial,” he said.

Chang said that these discussions are unfolding around the country. He noted that Arizona recently eliminated peremptory challenges (excluding a potential juror without citing a reason) in all jury trials, a change that Chief Justice González said he has long supported.

González said there is overwhelming acknowledgement that racial bias persists in the court system, but no universal agreement about how to address it. He said his court has the responsibility to initiate what he calls "hard discussions."

“I’m proud of our court for confronting it and dealing with it and discussing it, and I think what it’s led to is more discussions among attorneys, more training for judges and lawyers about implicit bias, and ways to eliminate and reduce it,” he said. “So I’m just glad that we’re engaging in that dialogue and not backing away from it.”

González said he’s not seeing lots of verdicts overturned by these new standards. Instead, he said lawyers in civil and criminal cases are changing their language and tactics to not run afoul of them.

In a statement provided to KUOW, the Washington Defense Trial Lawyers Association said it’s too soon to know the impact of the Henderson decision on other civil cases, adding that it “recognizes and respects the Washington State Supreme Court’s efforts to reduce the harmful effects of implicit bias in the jury system."

The statement continues, "Because Henderson was issued less than four months ago, its impact on future civil cases is unknown. Nonetheless, the WDTL is committed to working with all stakeholders in improving ways to remove all forms of bias from the jury system.”