Will Washington's long-term care program survive the election?

When Pat Johnson’s mom was aging, she needed help making meals, getting dressed, and bathing.

“We were very lucky we were able to hire someone part-time to come in a few hours in the morning, a few hours in the evening, to help her,” Johnson said. “And because of that, she was able to stay in an independent senior housing complex for a couple of years more than she would have otherwise.”

But not everyone is able to cover expenses like that out of pocket, and Medicare and health insurance don’t cover them either. Medicaid does — but only for people who qualify for Medicaid.

That’s why Washington state legislators created a program to fill the gap.

Washington state’s long-term care insurance is the first of its kind in the country. It’s a payroll tax that goes toward helping people cover certain health care costs later in life. Initiative 2124 will be on the ballot this fall and would give Washington state workers the ability to opt out of the program: not pay the tax, and not qualify for any benefits.

Sponsored

The median Washington worker pays in about $250 a year. Then, if they need help with three tasks of daily living — say, bathing, preparing meals, or driving — they can qualify for benefits.

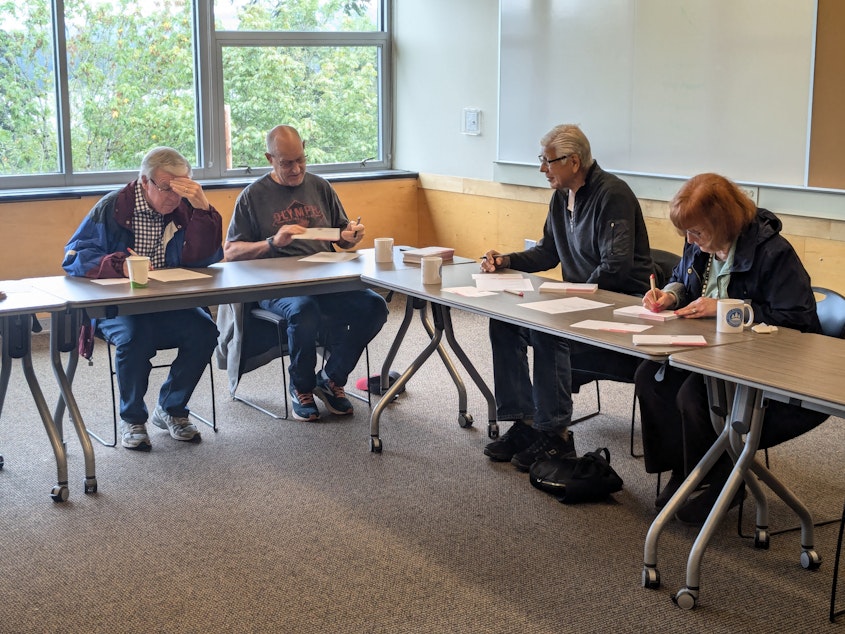

Last month, Johnson gathered with other members of the AARP at the Mercer Island Community Center to sign postcards urging others to vote down Initiative 2124, and keep the state’s long-term care benefit as it is.

The maximum payout is $36,500, a number that will grow with inflation. That’s only enough money to cover a few months in a long-term care facility, but it could cover many months of part-time in-home care.

“It helps you with those initial things, and it's so flexible,” Johnson said, explaining her support for the program. “You can use it for a caregiver. You can use it for transportation. You can use it for making accommodations, like a ramp.”

Giving people the ability to opt out would be the program’s death knell, said Cathy MacCaul, the policy director for the AARP in Washington.

“It destroys the financial solvency of the program,” she said. “The model is that everybody contributes in and pays a little bit because then it spreads the risk across a larger group of people.”

An analysis commissioned by the state government also concluded that, absent any other changes, Initiative 2124 would likely bankrupt the long-term care program.

MacCaul said she thinks a lot of people would opt out if given the choice. “People don’t think they’re going to age,” she said. “They don’t think they’re ever going to need care. And so we’re having to overcome that bias of people not wanting to think about the future, not planning for the future.”

Senator Mark Mullet is a Democrat, but he does not like this program — and he thinks a lot of Washington state residents felt the same way when it passed back in 2019.

Sponsored

“People were freaking out,” Mullet said. “They were like, ‘What did you guys pass? We don't like what you passed!’”

There was a brief window before the program launched when the state gave people the ability to opt out. About 500,000 people took that option. That’s 13% of Washington’s workers.

Mullet said he supports the initiative, because he thinks the program should still be optional.

“For people who want to stay in the program, they 100% can stay in the program,” Mullet said. “But for the people who felt like they were forced to basically just have the state policy, not what better suits their family, this creates the opt out and flexibility for people to do what works best for their families.”

For one thing, he said, it’s much harder to qualify for benefits if you retire out of state, so people who know they’re retiring out of state might want to opt out.

Sponsored

Mullet acknowledged that it’s possible that making the program optional would kill it entirely. But he views that as an opportunity, not a problem: a chance to redesign the program with the money that’s been paid into it so far.

“No one’s getting their money back,” Mullet said. “You’re going to have billions of dollars to create a program that works best for the people who really need it. To me, the best part is it does give people with pre-existing conditions the ability to have long-term care insurance. And you could design a plan that’s really geared towards that.”

The state’s only been collecting the tax for about a year, and no one’s eligible for any benefits until 2026 at the earliest.

Polling indicates that about 1 in 4 voters still haven’t decided how they come down on the initiative.