Whitewashing of Asian students and a report that launched a reckoning

A school district sparked fury after grouping Asian and white students together. The message was clear: 'Person of color' meant underperforming.

T

he outrage was immediate.

A report from North Thurston Public Schools in the Olympia/Lacey area went viral last November for lumping Asian and white students together because their test scores are roughly the same. Students of color — not including Asians — were a separate category.

The implication was clear: Person of color meant underperforming.

“Not all Asians are the same, and they’re not the same as white students,” said Erin Okuno, who is Japanese and Okinawan.

Sponsored

North Thurston pulled the report. “We messed up,” said spokesperson Courtney Schrieve. "We own it. We apologize to our Asian American community.”

The controversy hit home for me. I was a teacher at the International School, a majority-Asian school in Bellevue. I’m also biracial — Chinese and white.

While some Asian students come from families with privilege and education, many face poverty and language barriers that make school more challenging. Grouping Asian and white students together reinforces the harmful “model minority” myth, erasing these more vulnerable Asian students, who, like their Black and brown peers, face higher rates of discipline and lower rates of graduation with fewer opportunities to succeed.

When data on Asian students is disaggregated by ethnic groups, the evidence shows that not all Asians are alike, and some Asian communities are struggling significantly. Compounding this is a lack of Asian representation in equity goals and curricula, even within districts with large Asian populations.

North Thurston wasn’t alone in putting Asian students in the white category.

Sponsored

As recently as five years ago, Seattle did too, reminded Erin Okuno, the executive director of the Southeast Seattle Education Coalition. Okuno would like to see more precise data.

After all, “Asian” includes nearly 50 ethnic subgroups that speak over 2,000 different languages. Okuno said that when Asian student data is disaggregated, it’s evident that many Asian communities are not receiving adequate support.

I

reached out to Christina Joo, a former Bellevue student of mine, now a sophomore at Stanford University, for her thoughts on the North Thurston report. When she was in seventh grade, Joo, who is Korean, once asked me hopefully if Harper Lee, author of To Kill a Mockingbird, was Asian. In fact, none of the required books in our Bellevue middle school language arts curriculum were by Asian authors.

Sponsored

Initially, Joo said that she was angry and confused.

“The achievements I’ve made cannot be attributed to the same privileges as white kids,” she said. “Most of my Asian peers have done well, and given our immigrant barriers, often seem more mature.”

Joo, who is a first-generation immigrant, said she grew up making doctor’s appointments for her parents and arguing with customer service representatives. Given these responsibilities, she said, “it wouldn’t be justified to compare [first-generation Asian students] to the level of achievements of white students.”

But then her tone shifted.

“I am extremely privileged,” she said. “Not because I am rich (I am not) or because I have family in high places (I do not) , but because I have loving, supportive friends and family, was given extremely fortunate opportunities, and have good health that has allowed me to pursue everything I have.”

Sponsored

A

s a teacher, I saw that privilege play out in the assumptions of some of my white colleagues. Asian students, regardless of their behavioral or academic challenges, were often given the benefit of the doubt in a way that I did not see afforded to Black and brown students.

One particular Asian former student of mine comes to mind. She was quiet and sweet, and she turned in beautifully neat assignments, color-coded with gel pens. The only problem was that her lovely class notebooks and essays showed clear challenges with critical thinking and synthesizing of concepts. I looked at her record: unblemished, no special education recommendations, ‘A’ grades everywhere. When I talked with her previous teachers, they had no concerns. She had slipped through the cracks.

Joo continued: “A lot of our culture encourages, and at times, idolizes, academic achievement. Could this mean that our hard work needs, from a statistical standpoint, ‘grading on a curve’? We may not have the same privileges, but we do, or must, have some privileges.”

Sponsored

Perhaps this is what North Thurston and other school districts were doing by grouping Asian with white students — grading on a curve to give students who are farthest from educational justice a chance to catch up.

But category reconfiguring is not justice. And nobody wants to be erased.

A

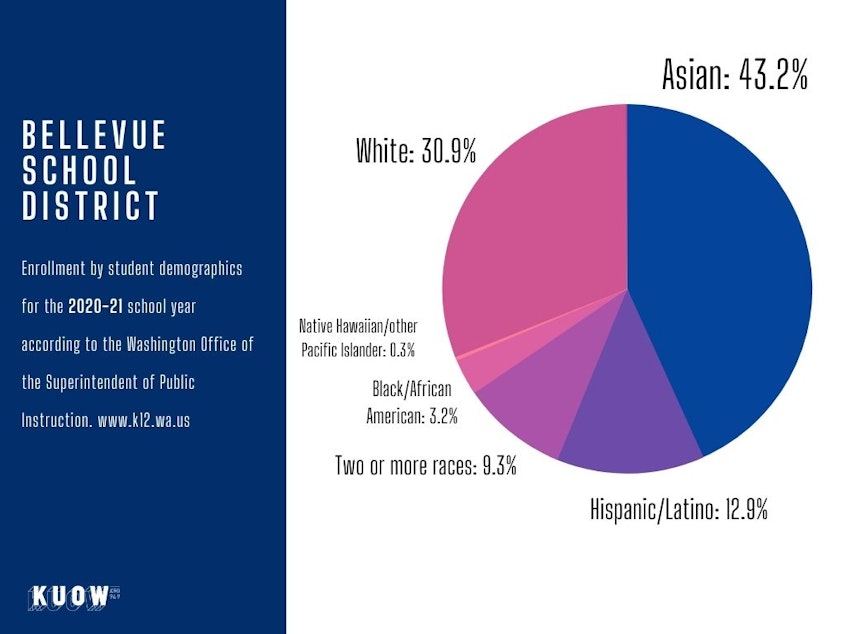

s a former teacher with the Bellevue School District, I think about the erasure of our Asian students a lot. Of all of the public school districts in Washington, Bellevue has the highest percentage of Asian students at 43.2%. At the International School, where I taught humanities from 2011 to 2017, Asian students now make up the majority of the student population.

During my six years with the International School, I taught sixth, seventh, and eighth grade. From my vantage point in the language arts department, in addition to more teachers of color that reflected the diversity of our students, the middle school curricula needed more diverse, robust, and current resources. When I joined Bellevue in 2011, the only literary work by an Asian author in the middle school humanities curriculum was Fish Cheeks, a short story by Amy Tan, published in 1987.

In slides from a 2016 presentation posted on Bellevue’s website entitled “Report on Equity,” Asian students are almost completely absent— even though they represent the largest ethnic group in the district.

On one slide listing the District’s focus areas for the equity department, under the heading “Launch & Assessment of Culturally Relevant Teaching,” there’s a clarification that this means Black and brown history. There is no mention of curricula focused on Asian history.

I asked the Bellevue School District about its current equity goals, inclusion of Asian authors in language arts curriculum, and efforts to recruit and retain Asian teachers.

About their lack of teachers who reflect the diversity of their students, Michael May, Bellevue's Director of Communications, said over email, "We aim to increase our educator diversity racially and ethnically to more closely align with our student demographics. For example, our student demographics indicate our student population identifies as 43.2% Asian, yet 13.23% of our certificated staff identify as Asian/Pacific Islander and 15% of our certificated administrative staff identify as Asian/Pacific Islander. The disparity is realized and thus our strategic hiring goals are aligned." You can read the statement in full here.

Here are a few points I noticed from Bellevue's statement:

- The District is taking ownership of the fact that their representation of Asian teachers is not proportional to the students they serve.

- There is no confirmation that any Asian authors have been added to the middle school humanities curriculum at the International School, although they do mention that Red Scarf Girl by Ji-li Jiang is part of the school's seventh grade history curriculum.

- Their hiring plans and equity goals highlight diversity in general, but do not speak to the Asian community in particular. This is in contrast to the way their 2016 presentation highlights Black and brown communities specifically.

- Asian themes in the curriculum appear to be limited to Bellevue’s social studies department.

S

chools have a shameful track record of relegating Black history to the shortest month of the year, and neglecting Hispanic and Latino history all together.

It’s also well documented that schools discipline Black and brown students more harshly and at markedly higher rates than other students, a discrepancy that negatively impacts not just the personal experiences of school for our Black and brown youth, but also their attendance records, test scores, and graduation rates.

In this context, it makes sense that districts would specifically include the teaching and evaluation of Black and brown history curricula in their equity goals. However, the absence of any mention of education that highlights the experiences of the fastest growing racial group in America is a significant omission, especially for a district serving a student body that is mostly Asian.

This is not a matter of pitting marginalized groups against each other or exchanging one history lesson for another. We need more inclusion, information, and clarity in both data and curricula, and we need our schools to reflect the diversity of the students they serve.

Furthermore, the “Asian” classification is already an especially vast one that includes on one end highly educated immigrants who came to the U.S. to work in lucrative industries, as well as refugees who moved here fleeing violence and poverty on the other.

In short, we are not a monolith, and the lesson plan opportunities are limitless.

M

arrene Franich, a Bellevue International School veteran with over 20 years of experience in the classroom, shared her perspective on who gets left out when Asian students are excluded from equity conversations. Franich is white and has a trans-racially adopted daughter who is Korean. I asked her how she thinks schools are doing in serving Asian students. Over email, she shared her concerns:

“The needs and experiences of Asian students have been neglected for some time,” Franich said. “Teachers tend to see Asian students as compliant and diligent, and if the student is not struggling to do the classwork, they may feel there's nothing to worry about.”

She continued: “Mental health issues (and other health issues) may go unrecognized at a high rate.”

Bach Mai Dolly Nguyen, who has a doctorate in education, has researched the hidden academic opportunity gaps in Asian communities in Washington.

She said that stereotypes about Asian students cloud the ability of educators to see the needs of students clearly. Nguyen said that the cruelty of the model minority myth is that when it is invoked for Asian students, all disenfranchised students suffer.

Over email, Dr. Nguyen shared a warning:

“Asian students could very well be performing at higher rates than their peers in some, or even many, contexts, and the point is not to counter that claim,” she said. “Rather, the key is that schools and districts that rely on assumptions about Asian students in lieu of comprehensive evaluations of students’ needs could be applying similarly detrimental assumptions to other racial groups for whom they express an explicit concern.”

In other words, if we’re stereotyping Asian students, it’s likely we’re stereotyping other students too. This is not what equity looks like.

F

or districts across Washington, race-based patterns of student performance are clear.

North Thurston, Seattle, and Bellevue reflect trends that are evident in districts across our state. Graduation rates are lowest for Black and Hispanic students. Our Native and Black students are being disciplined at markedly higher rates. Teachers are mostly white and female by a landslide. Asian students are out-performing their peers by many measures.

And yet.

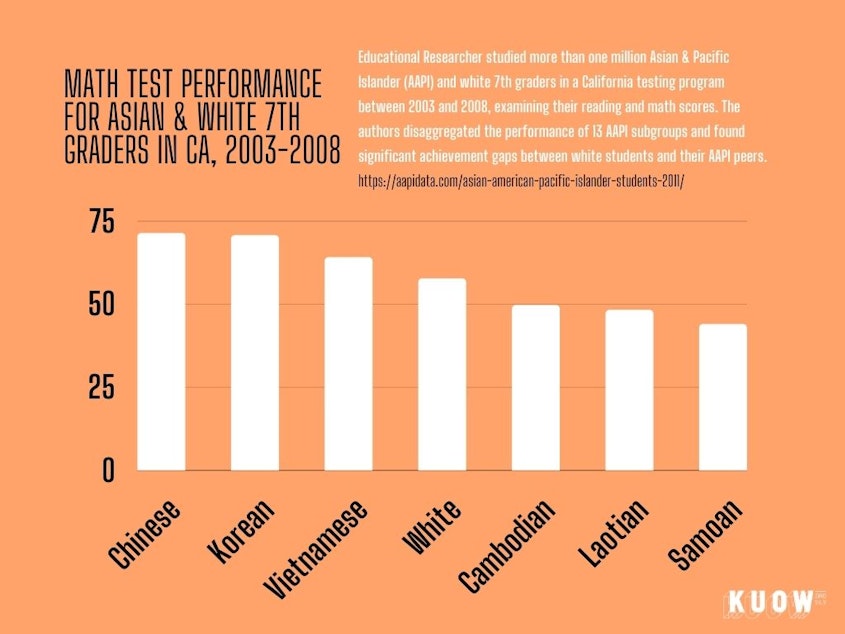

When data for Asian students is broken down by country of origin, it is clear that not all Asians are excelling. According to AAPI Data, a national publisher of research on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, while Chinese, Korean, and Japanese students in the U.S. may be prevailing on standardized tests, our Cambodian and Laotian students are struggling to keep up with peers.

Anti-Asian harassment and violence has also been on the rise both nationally and locally amidst the spread of the coronavirus, and that bias is infecting our schools.

In March, in a piece titled Coronavirus fears in Pacific NW lead to rise in anti-Asian racism, Crosscut reported that the anti-Asian harassment in schools was so significant that the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction released a bulletin clarifying that Washington school districts should “intentionally and persistently combat stigma” by reminding their communities that “the risk of COVID-19 is not at all connected to race, ethnicity, or nationality."

A

lot has changed since I left teaching four years ago.

From preschools to universities, campuses across the U.S. have been shaken awake as the Black Lives Matter movement and a modern civil rights reckoning has brought to light the culture of white supremacy embedded in our education system. But our schools still have a long way to go in supporting all students.

The students most often erased and disciplined out of their educational opportunities are the ones who have always been hit the hardest: our Black, brown, Native, and Pacific Islander students. Our students who qualify for free and reduced lunches. Our special needs students. Our English Language Learners. Our immigrant students. Our students who will be the first in their families to graduate from high school or attend college. Our LGBTQ students. Our housing insecure students.

Asian kids are included throughout these categories of our most vulnerable students. When Asian students are left out of equity work, that vulnerability deepens and challenges become barriers.

We ask students all the time to learn from their mistakes and keep striving to expand their understanding. Now it’s time for administrators, teachers, parents, everyone who makes up our school communities--get ready, that’s all of us--to do the same.

Kristin Leong, M.Ed. is KUOW's community engagement producer and Seattle Story Project editor. She is an international TED-Ed Innovative Educator and three-term Washington State Teacher Leader.

Note from Kristin: This is a complex topic, and I welcome your feedback. You can email me at kleong@kuow.org and find me on Twitter @kristinleong. I also welcome you to watch our YouTube conversation about this story that we recorded live - it features me, KUOW editor Isolde Raftery, Stanford student Christina Joo, and facilitator Zaki Hamid. It was a lively and surprisingly funny glimpse into how this story came to life, as well as an exploration of what more we have to do to keep moving forward. We're curious to hear your feedback about that live show too, as well as your ideas for what kinds of stories from the Asian community KUOW should look into next. Reach out. We're listening.

You can also submit feedback and questions about this story by emailing engage@kuow.org, leaving a voicemail at 206-221-1926, or texting the word “feedback” to 206-926-9955 to send a text.