When King County cops get their stories wrong, how should they correct them?

On June 13 last year, a King County Sheriff’s Office deputy fatally shot 20-year-old Vietnamese-American student Tommy Le in the back.

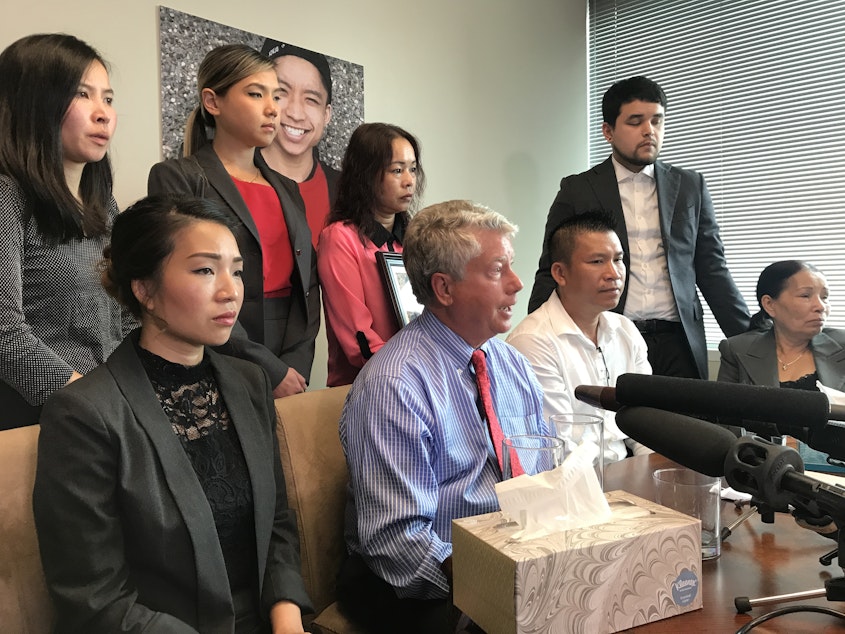

One day before the one-year anniversary of his death, members of the Le family gathered in the King County Council chambers to speak of the humiliation they felt following the shooting – and why, they said, no other families should have to experience what they did the night they learned their nephew and son was dead.

In the wake of Le’s death, the Sheriff’s Office told both the family and the press that Le had been holding a knife “or some sort of sharp object” at the time of his shooting. Several news outlets ran with this version of the story. But when the Seattle Weekly spoke to the Sheriff’s Office to follow up, the Weekly was told Le was carrying a pen.

It took more than a week after the shooting for the Sheriff’s Office to issue a statement acknowledging that Le was holding a pen in his hand, not a knife, when he was shot.

“It’s been a year of unending grief, shame, and humiliation for us,” Le’s aunt Uyen Le said in front of the King County Council. “And the only word we got from the county was ‘Sorry.’ So on this anniversary of Tommy’s death, we’re begging for more.”

The Le family’s appearance in King County Council chambers coincided with the release of a redacted report commissioned by the King County Office of Law Enforcement Oversight (OLEO) analyzing how King County police release information to the public.

The first four pages of the report, authored by Frank Lomonte, a University of Florida professor and director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information, were blacked out when released by the county. Those pages detailed the timeline of the Tommy Le shooting.

The county, King County Councilmember Larry Gossett said, could not discuss specifics of cases that were still under investigation. But Lomonte provided KUOW an unredacted copy of the report.

The report details how police departments across the country are dealing with community distrust, and specifically how to release information to the public. King County, the report notes, could be doing a better job.

Some of the biggest recommended changes, OLEO director Deborah Jacobs said, would be for police to inform family members before releasing names to the media, reaching out to ethnic media, and releasing regular updates about officer-involved shootings.

When police release inaccurate information, the report added, they should update that information as quickly and publicly as possible.

King County Sheriff Mitzi Johanknecht did not attend Tuesday’s meeting, but she did release a statement following Jacobs’ presentation.

“Since taking office, our administration has proactively released information, and accompanying documentation, quickly on a variety of issues,” Johanknecht said. “That information has been transmitted through public disclosure requests, press releases, on camera interviews and in social media posts so the information is easily obtained by anyone wishing to seek it.”

But while Johanknecht said she was committed to “a transparent and open relationship with the media and the public,” she did not commit to any of the report’s recommendations.

The Le family is still waiting for answers. Earlier this year, the family sued King County in federal court, alleging racial bias in Le’s death.

“It has been one year and the government has not done anything,” Le’s mother Dieu Ho said, speaking through a translator. "In our Vietnamese culture, this one-year death anniversary is the most saddening day for family. So we ask that you all help find justice for our Tommy and to help our family. “