What are we willing to do to protect Southern Resident orcas?

One of the amazing benefits of being a human in the Puget Sound region is our proximity to migrating orcas. We delight in their intelligence, beauty, and spirit. We celebrate them as icons in art and advertising. We go on excursions in hopes of seeing them up close. Their presence here affects who we think we are and what we think this place is.

For the orcas, our proximity and appreciation come with few benefits. We pollute their environment, disrupt the way they navigate and search for food with the noise we make, and diminish the availability of their main food source, chinook salmon. The Southern Resident population is declining. In 2005, they were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

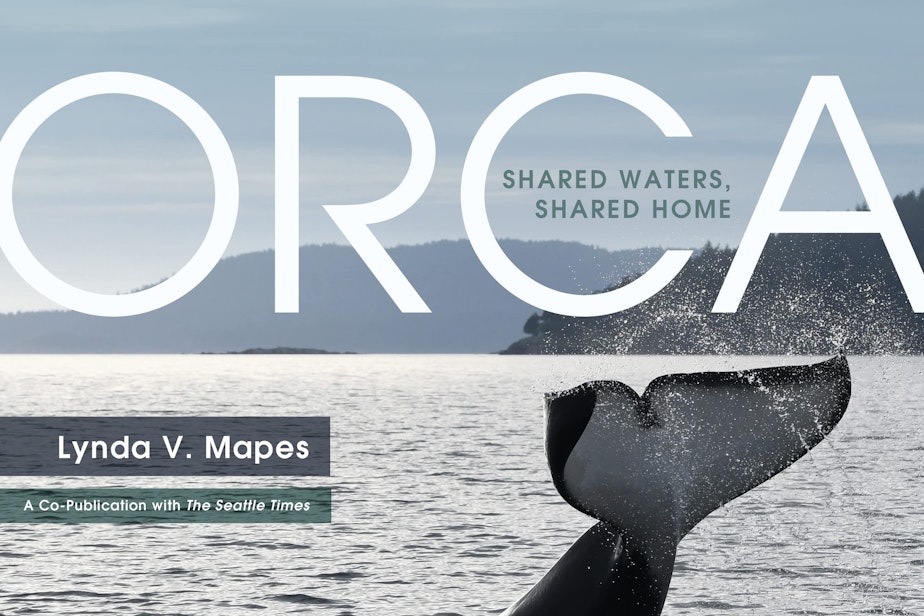

The status of our local orca population is the subject of Lynda V. Mapes’ new book Orca: Shared Waters, Shared Home. In it, she writes about their history, their interactions with humans, and what it will take to help them survive.

Orcas are an ancient species. The name the Coast Salish people gave them translates as “the people that live under the sea.” Local tribes honor them, in part for the bonds of family they display. The first generations of white settlers to this region killed them and later captured them for display in marine parks.

Members of the dolphin family, orcas inhabit every ocean of the world. The Southern Resident population is made up of three family groups referred to as the J, K, and L pods. In 1974, the first year they were counted, there were 71 individuals. That number rose to 97 in 1996. The official count for 2021 was back down to 73.

Lynda V. Mapes reports on natural history, environmental topics, and issues related to Pacific Northwest indigenous cultures for The Seattle Times. Town Hall Seattle presented this talk on November 18, 2021. Town Hall’s Wier Harman introduced the event.

Sponsored

If you have any feedback on this episode, you can email me at jobrien@kuow.org

Or you can just fill out the form below. We're listening.