'Cultural changes ahead' for police in Washington state, as controversial reform laws take effect

New laws governing Washington State law enforcement took effect on Sunday, including their use of force (HB 1310) and tactics (HB 1054).

Some police departments in King County say new laws means they will no longer respond to certain calls; City of Seattle chief Adrian Diaz calls that “absurd.”

T

he use of force law states, “It is the fundamental duty of law enforcement to preserve and protect all human life.”

It requires police to use de-escalation tactics and the minimal force necessary to overcome resistance. It also prohibits any use of physical force (ranging from handcuffing to deadly force) unless a person is committing a crime or poses an imminent threat of harm.

These reforms “may have the positive impact of reducing the number of violent interactions between law enforcement and the public,” wrote the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs in a statement – but the group warned that there could be "unintended outcomes" resulting in confusion, frustration and "increased crime."

Across King County, police chiefs say that the use of force law means that suspects could get away more easily, and they won’t be able to respond to some calls.

The city of Kent posted an interview with Police Chief Rafael Padilla, in which he said the laws may alter how his department responds to 911 calls, especially around people in crisis.

Sponsored

“If we say we aren’t coming, it probably falls under the category of these new restrictions that we can’t go,” Padilla said.

Democratic State Rep. Jesse Johnson, who sponsored the legislation, said there’s nothing in it to stop police from going to a scene.

“When I hear there’s some law enforcement agencies telling their officers not to show up, that’s a grave concern,” Johnson said. “We’ve made sure every department knows there’s nothing in the law to prevent them from doing that.”

Johnson said for most calls involving behavioral health crises, officers have the authority to detain someone or transport them to a hospital for involuntary commitment.

But he said there could be a problem when an officer shows up alone without a designated crisis responder to determine eligibility for involuntary commitment, “and it doesn’t look like the person needs to go, but the family’s asking them to go.”

Sponsored

Johnson said legislators plan to clarify that the use of force law does nothing to alter the Involuntary Treatment Act.

He said legislators will likely adjust the new law to make clear that a new ban on military-grade weapons won’t include “less-lethal” ammunition, like beanbag rounds.

State Sen. Manka Dhingra, who worked to pass the laws, said she believes police would have grounds to address crisis calls.

“There are always growing pains,” Dhingra said. “But I think those things will work themselves out. I think these bills go a very, very long way with helping to build trust.”

She said legislators would enact fixes if problems emerge.

Sponsored

The new use of force law raises the standard for when police can use force to detain someone who’s running away. Where they previously needed “reasonable suspicion” to stop someone believed to be involved in a crime, they now need “probable cause,” which requires more evidence.

Chief Padilla said the new law may allow suspects to flee.

“I may not, as a police officer, now be able to chase that person,” he said.

“Most police officers want to stop that person, want to do the investigation, and want to make sure the process is completed. So there will be some significant cultural changes.”

Sponsored

Rep. Johnson said, “We just don’t want the situation where the dispatcher calls and says there was a theft, and the person had a red hat, and the officer goes and finds anyone with a red hat and uses physical force to detain them based on reasonable suspicion but not probable cause,” he said.

“It ends up disproportionately impacting too many people especially in Black and brown communities based on profiling,” he said.

The law also restricts vehicle pursuits without probable cause, except in cases of impaired driving.

Federal Way said in a statement it is training all its officers in the new laws.

Chief Andy Hwang said the restrictions will “virtually eliminate all police pursuits.”

Sponsored

This also means more suspects will get away, he said.

An officer responding to a robbery or shooting may see a fleeing suspect vehicle and may have ‘reasonable suspicion’ but cannot pursue it because probable cause is not usually developed in the initial phase of an incident, he said.

Snohomish County Sheriff Adam Fortney said the laws will change his agency's approach to people in crisis:

“Deputy sheriffs can no longer use force, even minimal force, to detain a person in crisis for transportation to a hospital. The only instance a police officer may use force in this situation is if there is an imminent threat of bodily injury to a person. As a result, sheriff deputies will have to walk away from many crisis incidents far more often than in the past.”

The Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, which supported the laws and includes family members of people killed by police, issued a statement saying HB 1310 “removes the existing authority for officers to use any amount of force necessary to make an arrest, and replaces it with a reasonable care standard, requiring officers to de-escalate, use less lethal alternatives when possible, and use only the minimum amount of force necessary. This does not require officers to stay in their vehicles, or not respond to a call.”

In his statement, SPD interim Chief Adrian Diaz seemed to push back on some of the guidance by other agencies. “None of these laws in any way prohibit agencies from responding to calls for service,” he said.

He said that while “some agencies have declared they will no longer respond to calls involving subjects in behavioral crisis, that is not the position of our department.”

He continued: “The idea that the ability to use force is a pre-requisite to engaging in investigative stops or responding to individuals in crisis is absurd.”

However, Diaz said “officers will be expected to disengage” when there is no legal basis to use force against an “uncooperative or resistant subject.”

The use of force and tactics laws are just two of the most visible new laws now in effect – July 25 was also the effective date for laws requiring officers to intervene when they witness excessive force, and report potential misconduct; a law creating a new statewide agency to perform independent investigations of police deadly force incidents; and legislation expanding the Criminal Justice Training Commission and giving it greater authority to decertify officers for misconduct.

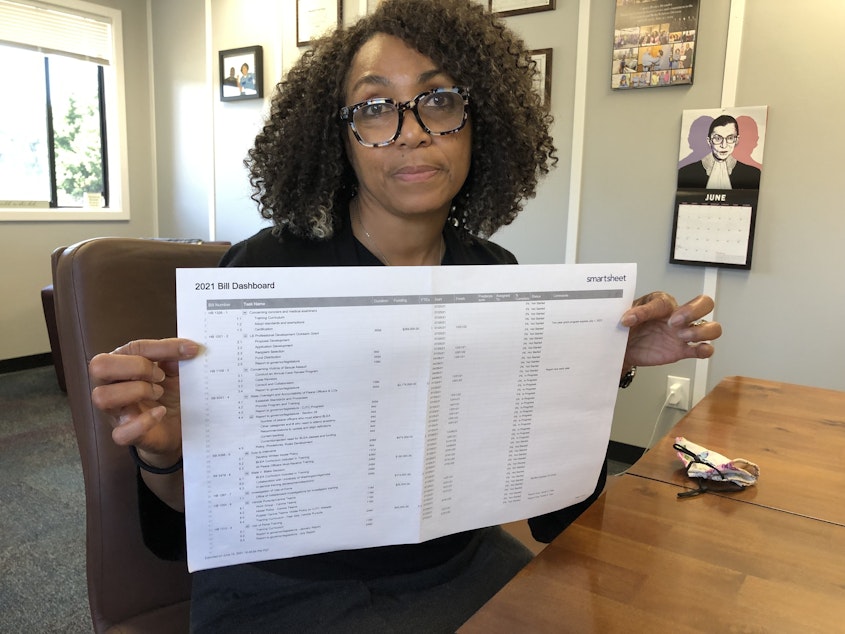

The CJTC’s Executive Director Monica Alexander said, “It’s so much, to the point where we have a spreadsheet” to track implementation of all the new legislation and advisory groups.

She said she’s heard a lot of concerns over how soon officers will be trained in the new use of force law.

“We’re going to do the very best we can to try and send the information out as soon as we make the necessary tweaks to the curriculum,” she said.