Washington state could elect its first Black woman to Congress this year

Washington has never elected a Black woman (or any Black person) to the U.S. Congress. But that could change this year.

Two Black women are running for the open U.S. House seat being vacated by Democratic Congressman Denny Heck.

Marilyn Strickland, a Democrat who served as mayor of Tacoma for nearly a decade and later ran Seattle’s Chamber of Commerce, is one of two Black women in the race for Washington’s 10th, which includes Olympia and part of Tacoma.

Strickland sees in the protests this spring against police brutality as a spark that could ignite historic change at the ballot drop box this fall.

“Our institutions, whether they're government, whether they're education, whether it's policing, whether it's banking, whether it's healthcare, what are the institutions doing? And how do we address the inequities that exist in them?” Strickland said.

Congress is one of those institutions. In 1968 Shirley Chisholm of New York became the first Black woman elected to congress. In 1972, she was the first woman and Black American person to run in a presidential primary.

Sponsored

But later in life Chisholm said neither “first” was how she wanted to be remembered. “I want to be remembered as a catalyst for change in America,” Chisholm said.

Half a century later there has never been a Black member of Congress elected from the Northwest. The list of states that have never elected an Black American person of any gender to congress includes Washington, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Alaska and Oregon.

Democrat Kristine Reeves is also running in the 10th here in Washington State. In 2016 she became first Black woman elected to the Washington State House in nearly 20 years.

Reeves said the protests this year against unconstitutional policing and racial inequity add urgency to the push to make a change in who represents us.

Sponsored

"I think what you're watching is people are tired of asking nicely for the change that we need to see in a government that should reflect all Americans. We're now demanding change.” Reeves said.

Reeves said part of that starts with policing.

“This is a culture that needs to be overhauled in a society that is using police as a weapon against its own citizens,” she said.

Reeves also says when it’s time to write new laws a change in representation matters because experience matters.

“Would I be honored to be the first African-American elected to Congress from the state? Absolutely. For me, it's more than just the color of my skin that matters. It's the uniqueness of the experience I bring," she said.

That experience includes run-ins with the police.

Sponsored

“Even as a candidate for the State House, I've got called the N-word six blocks from my house," Reeves said. "I had the police called on me at least six times depending on the neighborhoods that I would doorbell in because I wasn't their neighbor.”

But Reeves said other experiences like being in the foster care system and experiencing homelessness at age 16 also shape her, and what she would bring to Congress.

The 10th is no swing district; Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump here in 2016 by more than 10 percentage points. But the race is still getting national attention in part because of Strickland and Reeves.

The two women received a duel endorsement by a nonprofit called Higher Heights for America, which supports Black women running for office all over the U.S.

Sponsored

Glynda Carr, the head and co-founder, says Black American women have made steady progress in winning elections, but it’s still not enough.

“The 23 million Black women in this country are still underrepresented, and under-served,” Carr said

Carr said today Black women are around 8% of the total U.S. population, but only 4.6% of Congress.

Nevertheless, Carr said there has been some progress.

“What we've seen over the last several election cycles is a steady increase in the number of Black woman running in a number of Black women winning,” she said.

Sponsored

For example, in 2018 Black women candidates won for the first time in three states: Massachusetts, Connecticut and Minnesota.

Carr also said more Black women are winning in districts that don’t have majority-minority populations (like Washington’s 10th).

Kelly Dittmar, a political science professor at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, said winning seats in districts like Washington's 10th, which is over 75% white, will be key for Black women to make future gains in Congress.

“For a long time Black women have been sort of niched into majority-minority districts only. There's an impression, particularly among what have been dominantly white male political strategists, that that's where Black women can win,” Dittmar said.

But Dittmar said the evidence suggests this old conventional wisdom is wrong.

“We've shown time and again that Black women can win outside of those spaces, and outside of those districts. In 2018, four of the five freshmen Black women who were successful won in majority white districts," Dittmar said.

But there’s still a long way to go. Only 19 states have ever elected a Black woman to Congress. That means if Strickland or Reeves win this year in Washington state, that number would move to just 20 out of 50 states.

Carr argued the other key for long-term change is for more Black women to run at the state and local level, like Strickland and Reeves did, to keep adding to the pool of qualified candidates who run for higher office.

“It's about us encouraging training and supporting Black women to run for local office and then encouraging them to consider running for higher office,” Carr said.

And this year in Washington, there are several Black women running for the state Legislature, including two in the 37th Legislative District (position 2) in Seattle.

The seat is being vacated by Democrat Eric Pettigrew, a Black man who announced he would step down earlier this year, in part to take on a new job with Seattle's National Hockey League.

One candidate is Kirsten Harris-Talley, an activist who served briefly on the Seattle City Council in 2017. She sees in the protests themselves the possibility of deep, structural change, which would involve “investing in communities” rather than policing.

Harris-Talley said the transition from protesting to also embracing politics will be key this fall.

"All of the structures that are built in which the police do their work and in which community responds to how the police does their work, is wholly political," she said.

Harris-Talley also said a transformation that involves more Black people getting elected is necessary and long overdue and has stalled "since the Civil Rights movement."

But she said it’s not enough to elect a Congress that “looks like” a state like Washington, which has relatively few Black, Indigenous and People of Color compared to some other states.

“We need far more percentages than our standard percentage in the population, because of the way Washington state was built, and how it keeps Black, Brown, Indigenous folks from having high numbers here, we're going to need a lot to actually have enough voice to make the kind of change we need to see,” Harris-Talley said.

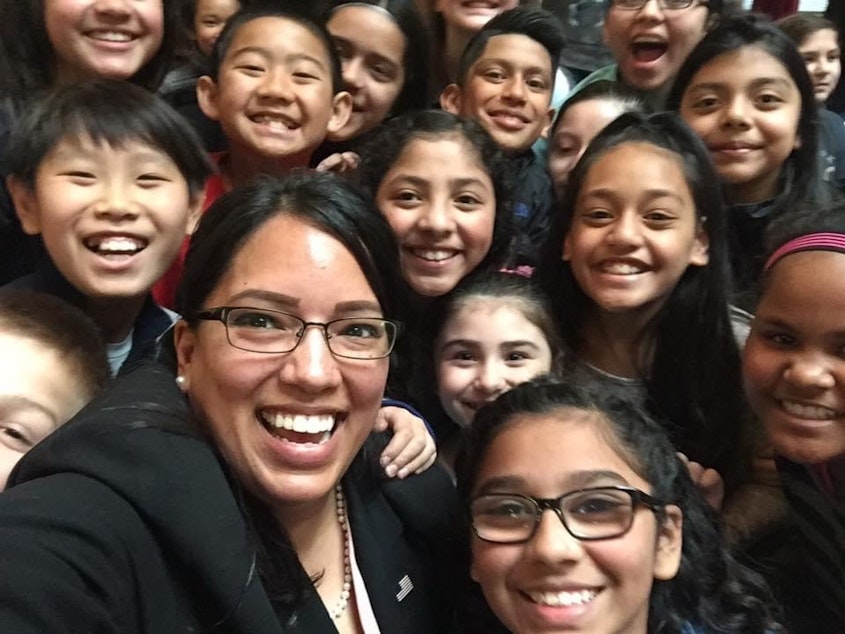

Andrea Caupain is also running for the 37th (position 2). She's CEO of Byrd Barr Place, formerly the Central Area Motivation Program (CAMP) which provides low-income services and support.

Caupain said she is "hopeful" that the momentum generated by political protests this spring will turn into legislative gains for Black people, including Black women, this fall.

“More people of color, and especially women are, are wanting to take action in different ways. And one of those ways is gaining a seat in the halls of power,” Caupain said.

She said the conversations she's having with voters have changed in the last few months.

"Now I'm having conversations about how we apply a race and social justice equity lens to policy-making at the state level, which is exciting. I have white people asking me that," she said.

"They understand that the system needs to be dismantled. They understand the system has not been working for a great majority of vulnerable people, including the Black community," Caupain said, adding that change will occur when more Black women and other people with firsthand experience of systemic racism and inequity have a seat at the table.

"There’s power in us being able to tell our own stories," she said.