Small slip of paper stands between Pacific Islanders in Washington and unemployment benefits

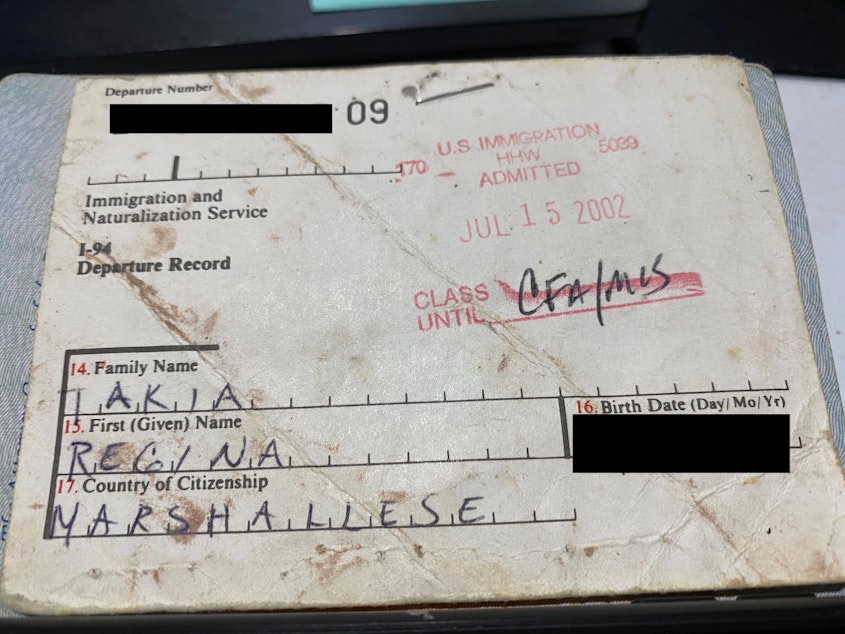

It’s a little slip of paper, smaller than a cell phone.

And having it can determine whether you get unemployment benefits or not.

That’s if you’re from certain Pacific Island nations – the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau, which have a special agreement with the United States allowing their citizens to live, work, and study in the U.S. without a visa.

In the time of Covid-19, everyone is at risk when one community can’t access safety net programs allowing them to stay home. Instead of staying in isolation, people with Covid may have to venture out to work to survive, advocates say.

The problems caused by that slip of paper are one of a series of sometimes insurmountable barriers migrants face when applying for unemployment benefits.

Advocates say the barriers, especially acute for some Pacific Islanders, amount to discrimination.

People from those nations don’t need the slip of paper to apply for a job — only if they lose the job and apply for unemployment benefits.

Sponsored

A lost number costs $445 to replace, unless you happen to know the workarounds in the state’s online unemployment system: Which boxes to click and options to select.

But the state has yet to inform the community about the workarounds and says it can’t modify the website instead.

“We haven't set up the processes in a way that they would have a disparate impact on people,” said Teresa Eckstein, the Employment Security Department’s Equal Opportunity director. “As we understand that certain groups are having more difficulty than others, we're trying to respond to that quickly and get them access.”

Cecilia Takiah Heine — who goes by CeCe — is a Marshallese community advocate.

Sponsored

She first delved into the depths of the unemployment system's bureaucratic minutia when she helped her brother apply and claim his benefits this year.

Then other family members started reaching out — then people from the broader community.

Perhaps it was the cultural values she was raised with to always be conscious of others, or perhaps it was her Catholic education that motivated her. But she decided to dedicate herself to helping others in the community with unemployment application woes, she said.

“Any way or any time I can help you, I will help you,” she told people.

Soon, she received a flood of requests.

Sponsored

Of all states in the U.S., Washington is home to the third largest population of migrants from the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau – collectively known as COFA migrants in the wake of agreements, or compacts of free association, their nations have signed with the United States.

An estimated 7,300 migrants were in Washington from 2013 to 2018, according to a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office report.

Heine works for the social service nonprofit Neighborhood House and serves as the treasurer of the Marshallese Women’s Association.

In April, Heine posted a 47-second video on Facebook in the Marshallese language offering to help people with unemployment applications. The video was viewed 7,000 times at the time this story was published.

People from across the U.S. reached out, and she recounts how she even helped someone in Indiana successfully appeal a denial and get benefits.

Sponsored

Heine helped Everett resident Maria Makaya, a mother of seven who is originally from the Marshall Islands. Makaya works at a medical device supply factory, and her hours were reduced when demand fell during the pandemic.

On June 6, she applied for benefits to replace her lost income, she said. Makaya filled out the forms herself, but unwittingly made mistakes.

In the meantime, Makaya and her family went in and out of quarantine and isolation for Covid-19 three times: First because her mother tested positive, then because a carpool buddy did, and finally because Makaya had Covid-19.

She and her family relied on sick leave and vacation time from her husband’s job, plus charity from a local church. But they fell behind on rent and utilities, Makaya said.

Finally, Heine intervened and straightened out the errors in Makaya’s forms. Makaya received $3,000 on July 27, and she was able to pay off her bills.

Sponsored

“I think unemployment is a good thing, it’s very helpful,” Makaya said through an interpreter. “The problem is it takes a very long time to get through it and to get any benefits from it.”

Instead, she encourages people to find other work or resources, she said.

"Nigh unto impossible"

Language is a major barrier to accessing unemployment benefits.

As a Marshallese interpreter based in St. Louis, David Utter often finds himself in the middle of calls attempting to navigate unemployment benefits, he said.

A common scenario involves four people on the call: A social worker, an older Marshallese person, and the Washington Employment Security Department.

“Usually it’s a good hour or so, and usually it does not conclude,” Utter said. “There's usually a follow-up call after that to finish everything.”

An application is “nigh unto impossible” to complete without substantial help for people who don’t have English, Utter said.

Or proficiency in technology, another major hurdle for many people.

The online application for Washington state isn’t mobile-enabled, and it’s clunky and frustrating to scroll around on the desktop version on the smaller screen of a mobile device.

Most people Heine has helped don’t have computers at home, she said. The same goes for Chuukese Micronesian migrants helped by advocate Triple Js Kaminanga.

Low wages from their jobs at the airport, restaurants and factories, for example, put home desktop computers or laptops out of reach, she said.

Rachel Hoffman, Marshallese Women’s Association secretary, has helped a handful of people apply for unemployment, she said.

Internet network glitches can also make the online portal inaccessible, she said. “A lot of our families have the least expensive data plans,” Hoffman said. “When it's least expensive, you know, the quality isn't so great.”

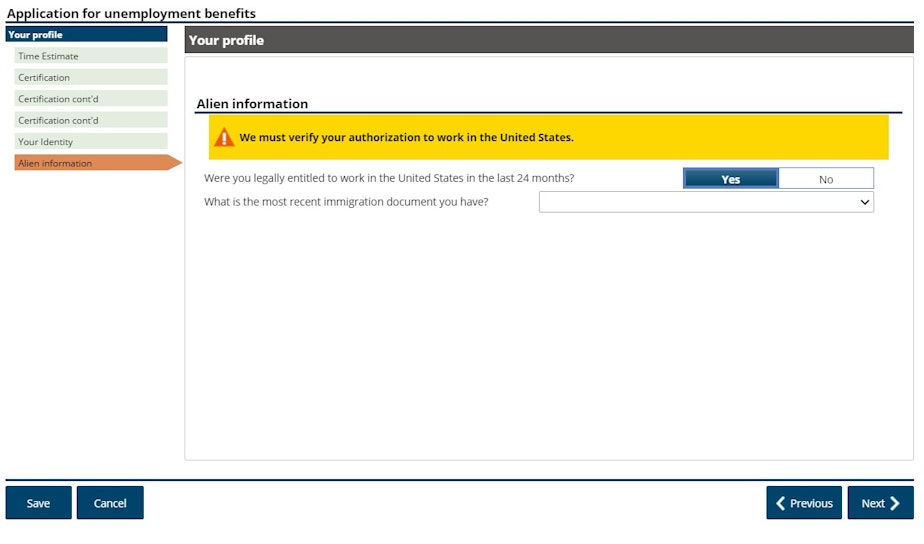

On top of that, when it comes to the I-94 migration document, “expiration date” is a required field in the online application.

The only thing is, the form does not expire for these migrants.

“And that's when people just don't know what else to do,” Kaminanga said. “They will just stop and start looking for another job.”

Heine calls it discriminatory.

“You discriminate against me because I don't expire,” Heine said.

The Employment Security Department online application has workarounds to the required expiration date fields, but you have to know which buttons to click.

Just leave a drop-down menu blank when it asks you to select a specific immigration document, said Eckstein with the Employment Security Department’s Equal Opportunity division.

The Employment Security Department plans to publicize this workaround online and through a town hall, Eckstein added.

Heine said she hadn’t heard of the workarounds at the time this story was published.

In the case of a missing I-94, Employment Security staff can use other documents and reach out to Homeland Security directly to verify the applicant is authorized to work in the U.S., Eckstein said.

The department is working with community leaders to go through unemployment applications one by one and refine the system, Eckstein said. So far, they’ve resolved claims from 88 community members, she said, out of 115 referred to them.

The department plans to hire at least 20 more unemployment specialists who speak languages including Marshallese and Chuukese.

“It's really important to us that technology and language aren't a barrier,” she said. “It shouldn't matter when people need unemployment, that they have a language barrier or there's a technology barrier. So we're trying to remove that.”

The Employment Security Department did not answer why they can’t modify the website.

Before the pandemic, applicants could get help in their language over the phone or in-person. But now, in-person offices are closed and the phone lines are overwhelmed.

“We had good systems in place. But I think that just this wave of unemployment has made it really difficult,” Eckstein said.

And these barriers pose a risk during the pandemic.

Covid-19 has infected, hospitalized, and killed Pacific Islanders in Washington state at rates many times higher than white people, according to data from the state Department of Health.

A combination of factors creates this disproportionate risk. Among them are low-paying jobs in “essential fields,” multiple generations living in close quarters under one roof, and a lack of access to safety net programs.

Many people’s main concern is making sure there is money for rent, food and to support their kids, mom, and elderly relatives, Heine said.

“Most of us live check-by-check — there are no savings,” Heine said. “So if we don't have any other access to any financial support, we will continue to work regardless of if we're sick or not.”

Underneath the injustices of the pandemic, a terrible history reverberates.

“We can't call it history because the impacts are still with us in our communities, even in America today,” said Hoffman, the Marshallese Women’s Association secretary. “It has impacted our health, it has impacted our entire lifestyle.”

The United States caused large-scale radioactive contamination of the Marshall Islands through 67 nuclear tests between 1946 and 1958, including detonation of a bomb over 1,000 times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

While people from these Pacific Island nations can freely live and work in the United States, they are ineligible for many federal programs available to immigrants.

“Now we're coming to the U.S., but we really don't have any help from you,” Heine said. “When you needed our help, we gave it to you so you could win your Cold War.”