This hotline gave immigrants a lifeline as Covid ripped through the Seattle area

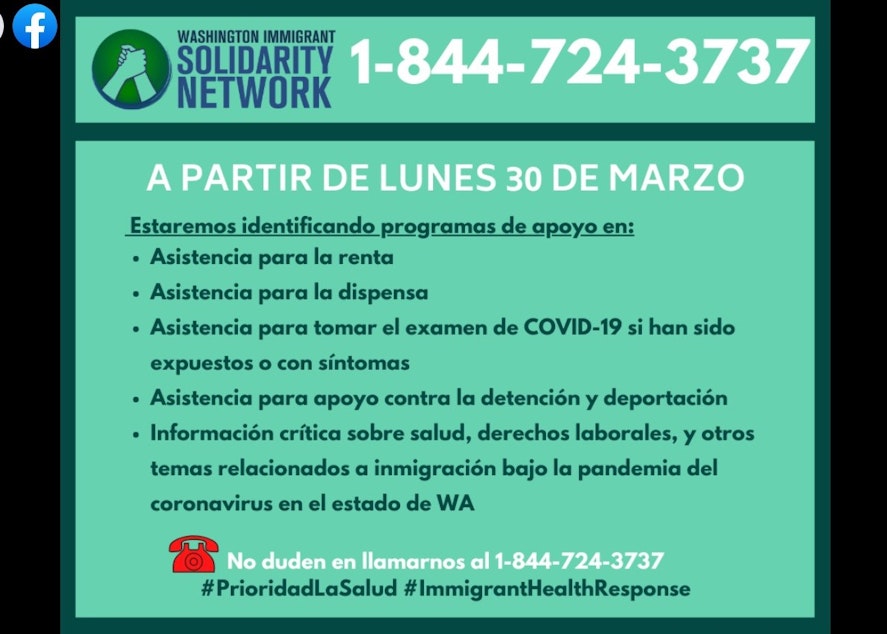

A year ago, Monserrat Padilla and her colleagues posted a phone number to Facebook.

“We told people, you can call us for rental assistance, access to food,” said Padilla, a co-director of Washington Immigrant Solidary Network. They also helped connect folks with Covid testing and legal help.

The line was almost immediately overwhelmed, with 500 missed calls by 2 p.m. the next day.

The hotline was flooded because it helped people regardless of their immigration status. Undocumented people are not eligible for unemployment insurance or federal stimulus aid.

“Undocumented communities were left behind from any form of safety net program that provided income for the house,” Padilla said.

The hotline got 750 calls in 2019. Now it averages around 500 calls a week, she said.

Volunteers route callers to any number of potentially helpful local resources listed in a database the organization compiled.

Sponsored

The Washington Immigrant Solidary Network (WAISN), where Padilla works, is a coalition of organizations that came together after Donald Trump’s election in 2016. At that time, the hotline was a place people could turn – for example – to report immigration enforcement agents in their neighborhood and to summon witnesses if someone was being deported.

When the pandemic hit, these groups that had been working together for years were well positioned to pivot to new needs, and the established trusting relationship with the community paid off.

“They knew that they could call us when immigration was out there,” Padilla said. “They had someone to finally talk to.”

Networks of support are a natural response to crisis.

Sponsored

“As immigrant communities, we've learned to take care of each other,” Padilla said. “That's a unique story that, while we talk about this crisis, it has not been told enough.”

This hotline is one point in a constellation of efforts that have emerged during the pandemic and align themselves with the principle of mutual aid.

Some groups use the term in their name, some don’t. It’s hard to know just how vast the community response is.

“Mutual aid exists on a spectrum of formality,” said Cyndy Wilson, an organizer with community group, Uprooted & Rising, which runs a food pantry in Burien for 100-200 families along with mutual aid organizations in Seattle and King County.

“It's kind of like asking, ‘How many communities are helping each other when they need help?’” Wilson said.

Sponsored

The term “mutual aid” may have taken off during the pandemic, but it’s nothing new, fellow Uprooted & Rising organizer Johnny Fikru said.

“For a lot of lot of communities – particularly Black, Indigenous, people of color communities – mutual aid has been part of our cultural lineage,” Fikru said. “Caring for each other, showing up for each other.”

What sets it apart from charity is that mutual aid is about reciprocity, relationship-building and social change, said Wilson, citing the teachings of local writer and activist Dean Spade.

“What does it look like to be in community with people rather than just dropping in and giving them stuff, then leaving,” Wilson said. “What does it look like to actually build power with each other?”

Sponsored

Before the pandemic Pastor Gerardo Guzman served as a witness deployed to document ongoing immigration enforcement activity.

He said he used to trail immigration agents and when they stopped in front of a house, he would call the resident and alert them not to go outside, “Vecino no salgas!”

Nowadays, he’s quite busy feeding people.

Twice a week El Dios Viviente in White Center distributes food to hundreds of families at a time. Volunteers greet drivers and load up cars with heavy boxes of milk, eggs, fruit and vegetables.

Some recipients are referred here through the WAISN hotline.

Sponsored

Different churches and organizations donate the food.

“You give your little bit, and I give my little bit, and another person gives their little bit, and we’ll do great things,” he says in Spanish.

On this day Gracia Diego and her husband Alfredo are here picking up a box for relatives – a family of five unable to leave home because they are sick with Covid. “The food they give here helps us,” said Gracia Diego in Spanish.

Another organization receiving referrals from the WAISN hotline is Burien/White Center Community Support Network.

Volunteer Irene Danysh talks with folks in her area who call the hotline.

“Does the person need food assistance? Does the person need a lawyer? Do they need some referrals about places to live?” Danysh said. She also asks about their hopes, plans and dreams, she said. “I really become a friend,” Danysh said.

And that’s another benefit of these networks, during times of crisis people can connect for the first time… and older relationships can grow deeper.

A friend Danysh met doing immigration advocacy before the pandemic is now a housemate.

Last year Maria Gonzalez needed a place to live after her husband got stuck in Guatemala during what they thought would be a quick trip to get a visa.

Danysh invited her to stay. Her motivation to help springs from her personal background, Danysh said. Danysh’s parents are refugees from Ukraine.

“All my life I felt like – well, I’m an American citizen, technically – but really part of the immigrant community wherever I’m living,” she said.

During this scary, lonely time, Gonzalez says she hasn’t felt that way.

“I haven’t alone. I’ve felt supported, safe,” Gonzalez said in Spanish. “I’ve felt very good.”

Danysh and Gonzalez sit together, chatting and drinking coffee in the woods behind the house. The arrangement is working out, and when Gonzalez’s husband returns, they plan for him to move in too.

One more person, hopefully safely settled soon, within this vast, unofficial safety net.