Photographic evidence of climate change underway in the Northwest

Climate change is not a scary thing that might happen in the future. It is here.

The photos below show how striking a role climate change has already played in the Pacific Northwest — helping to push houses into the ocean and wildfires to spread.

Here are some ways that climate change is already altering the region.

King tides are increasing

These extreme tides used to happen once or twice a year, when the moon comes closest to the earth. Scientists say king tides are worth paying attention to, because sea levels are rising, and that they will become more common as climate change worsens.

Three king tides are predicted for Seattle this winter, between end of November and January.

Wildfires benefit from warmer weather

It's warmer in the West than it used to be, by nearly 2 degrees.

This means that wildfires have a better chance of spreading because of dryer soil and dry shrubs and trees.

Wildfires burn more than twice the area they did in 1970, according to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

Beaches are eroding more quickly

Nicknamed Washaway Beach, the north side of Willapa Bay in Pacific County, Washington has eroded an average of 100 feet or more per year. Over decades, ocean waves have taken a cannery, a lighthouse, school, Grange hall, post office, and innumerable homes and vacation getaways.

Some geologists say this would happen without climate change, however, and that erosion is occurring because the North American tectonic plate is colliding with an oceanic plate.

While some shoreline erosion is natural, major episodes of erosion occur during big storms — especially when big storms are coupled with high tides.

Trees are dying in Washington state

So many dead evergreens. Why?

Kevin Zobrist, forestry professor at Washington State University, told us that his top suspect is drought.

“Drought stress from climate change,” he said. “We've seen records being set for heat and drought in a number of years in a row now, starting with 2012.”

[Read Eilis O'Neill's story on the case of Washington's dying foliage.]

These adorable, real-life Pikachu aren't adapting to climate change

Pikas like it cold, and as the climate has warmed, they’ve disappeared from lower elevations where they used to live.

For years, scientists thought pikas were adapting to climate change by moving uphill. But new research indicates the news is even worse than that.

Pikas aren’t adapting to climate change by moving uphill. In fact, because of the way they move around the landscape, they’re not adapting to climate change at all.

[Read Eilis O'Neill's story on what's happening with pikas in the Northwest.]

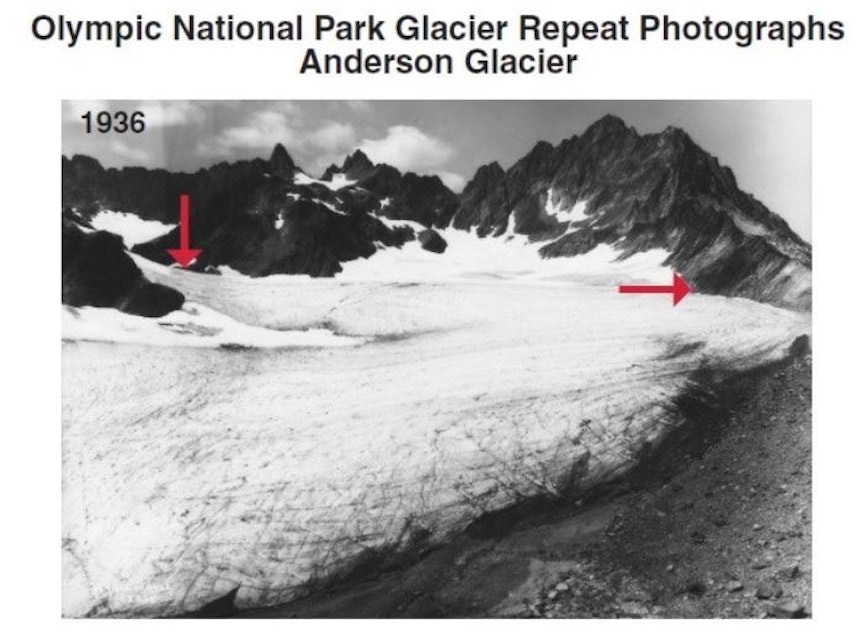

Glaciers are melting, three feet a year

From the National Park Service:

"To grow, a glacier must receive more snow in winter than melts or evaporates the following summer. If more melts than accumulates, a glacier will shrink."

In 1982, Olympic National Park had 266 glaciers; in 2009 there were 184.

When the snow melts, anxiety rises

Dagmar Devere's house burned in the 2014 Carlton Complex Fire.

Wildfire season is now a time of high anxiety for Devere. She sleeps little and spends hours online. Seeing or smelling smoke triggers her, until she gets the information she needs to understand what is going on and if there is any danger.

...and fire efforts become part of August vacation in eastern Washington.

[See more photos like the one above by amateur photographer Ben Brooks: Sunbathers gawked as wildfires burned Chelan.]

Our orcas are dying

The orcas in Puget Sound eat Chinook salmon primarily. But there are fewer of these fish because of habitat loss, caused by dams and hatcheries.

Changing ocean conditions, which might in part be caused by human-caused climate change, might play a role as well. Climate change is likely to play a bigger role in coming years.

Pollution and boat noise have also greatly stressed the whales.

And the little red fish of Lake Sammamish could be a summer away from extinction

The lake's populations of kokanee, a variety of sockeye salmon that never leaves fresh water, often fluctuate. But they have plummeted drastically in the past four years.

Just 19 of them headed upstream from Lake Sammamish to spawn in fall 2017. Six years ago, that number exceeded 18,000.

The clams are also disappearing

“They are delicious when steamed open and dipped in hot butter,” according to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

They’re also disappearing, according to scientists who've studied them from Alaska to California.

They suspect that changing ocean conditions, fueled by a warming climate, have left less algae in the ocean for clams to slurp up.

These littleneck clams are golf ball-sized bivalves that have sustained the Jamestown S’Klallam and other Northwest tribes for centuries.

The fewest sockeye salmon ever were counted at Ballard Locks this summer

Sockeye salmon are returning to Lake Washington in the smallest numbers since record-keeping started.

As of early August, 17,000 sockeye had returned from the ocean, compared to hundreds of thousands at their peak years.

Aaron Bosworth, a state biologist, blames climate change. Life is getting harder for sockeye salmon in the oceans, with warmer water and less food.

Things are also worse for young salmon upstream. For example, other fish that eat them are more active as Lake Washington heats up earlier and stays warm for longer.

An island is slowly disappearing in Alaska

About 374 people live on Kivalina, an island in Alaska that is predicted to be underwater by 2025 because of rising sea levels.

A view of the sea near Kivalina in May

The ice had broken up in two days when this photo was taken by photographer Suzanne Tenant in 2014. Normally it would have been solid into June, with break-up lasting several weeks, during which time the villagers hunt bearded seal.

With such thin ice that breaks up quickly, hunting whale in April is increasingly dangerous, while the bearded seal hunt is almost impossible.

This photo story was produced by Isolde Raftery, using reporting from stories by Ashley Ahearn, Tom Banse, Anna Boiko-Weyrauch, Joshua McNichols, Eilis O'Neill, John Ryan, and Suzanne Tenant.