The Tokyo Olympics Has Relaxed Its Rules On Athlete Protests — To A Point

Protests by athletes have become common and more widely embraced in the last few years, and the Olympics has updated its rules to allow for it – within limits.

The International Olympic Committee – the IOC – put out new guidelines earlier this month about how athletes may "express their views."

According to the new rules, athletes can express their views on the field of play prior to the start of competition, or during the introduction of the athlete or team. That's as long as the gesture is consistent with the principles of Olympism, isn't targeted against "people, countries, organisations and/or their dignity," and isn't disruptive.

What's considered disruptive? The IOC offers as examples expressions during another team's national anthem or unfurling a banner during another team's introduction. Beyond that, it's murky.

There are a few places where expressions are specifically banned: during official ceremonies, during competition on the field of play, and in the Olympic Village.

The guidelines on expression only apply within Olympic venues and during the Olympic Games.

Athletes are allowed to express their views when speaking to media, at press conferences, or on social media.

When it comes to clothing, the IOC will allow athletes to wear apparel at Olympic venues with words like Peace, Respect, Solidarity, Inclusion and Equality. But phrases like "Black Lives Matter" aren't part of the messaging.

The rules on expression pertain to Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter, which states that "No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas."

The latest guidelines say that the aim is to keep the focus at the Olympics on athletes' performances and on international unity and harmony — and that neutrality is a fundamental principle at the games. Athletes' expressions on the field of play during competitions or official ceremonies could distract from celebration of sporting performances, they say.

The IOC's Athletes' Commission, an elected body, said in April it had consulted with over 3,500 athletes regarding Rule 50. Athletes clearly had diverging opinions.

The Athletes' Commission said that in a study, 70% of respondents said it's not appropriate to demonstrate or express their views on the field of play or at official ceremonies. Others disagreed: "[S]ome athlete representatives took a different view, using freedom of expression and freedom of speech as their argument, and felt that this outweighed the other arguments."

Dr. Harry Edwards, American sociologist and co-creator of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, has some questions about who is reflected in those numbers.

"When you're talking 70 percent of the athletes, who are you talking about?" Edwards told Yahoo News. "They didn't say 70 percent of the Black athletes."

The Athletes' Commission raised another issue when it comes to free expression: the risk that athletes may be put under external pressure to make political statements.

"It is important to protect athletes from the potential consequences of being placed in a position where they may be forced to take a public position on a particular domestic or international issue, regardless of their beliefs," the commission said in its recommendations. In such situations, it noted, official Olympic neutrality can protect athletes from political interference or exploitation.

Because the guidelines aren't particularly clear on what is allowable protest, there's a lot of room for allegations in the days ahead that certain athletes have crossed the line, thus prompting possible discipline from the IOC.

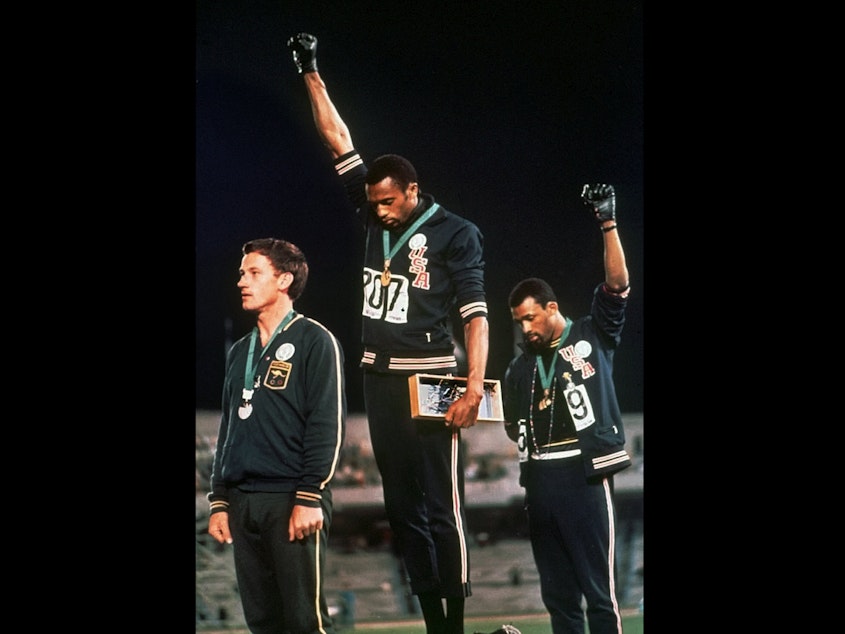

"Without a doubt, somebody is going to make a statement," John Carlos, who raised his black-gloved fist alongside teammate Tommie Smith on the podium at the 1968 Olympics, told The Undefeated.

When that happens, some IOC officials "are going to come after them, try to make a mockery of them," Carlos told the sports and culture site. "The difference is, 53 years ago they could mislead people. I don't think they can lead people as blindly now as they did 53 years ago." Carlos and Smith were both sent home and banned from future Olympic Games.

In Tokyo, athletes didn't even wait for the games to officially start to exercise their right to protest.

In three women's soccer matches on Wednesday, players made overt gestures against racism. Britain and Chile took a knee at their match, as did the U.S. and Sweden an hour later at theirs. New Zealand's team also knelt, while Australia's squad posed with an indigenous flag and linked arms.

It remains to be seen what other protests take shape in an Olympic Games like no other — and which protests Olympic officials will decide are fair play. [Copyright 2021 NPR]