The doula who delivers hope for Puget Sound’s marginalized mothers

Erika Davis loves making life grow.

Her front yard is covered with tall corn, sprawling kale and cucumbers. Inside her Tacoma home, green ivy falls along her bookshelves. She motions towards a corner of the house where a garden spider sits still.

“She keeps making her web there, so we just let her be,” Davis says.

Davis has been a doula for six years and says she’s helped more than 20 individuals and families give birth. A self-described “black, Jewish, dyke,” her training started in Brooklyn, New York where she realized she didn’t want to be a midwife. She decided instead to become a doula.

Doulas provide a wide range of pregnancy and childbirth support, which can include childbirth education, prenatal and postpartum care.

“I like to say a doula is from the waist up, and a midwife is from the belly button down,” Davis explains.

Though doulas are not medical professionals, some parents and moms are turning to midwives and doulas instead of traditional hospitals for more support during the birth process.

While Davis warns they’re not the magic wands to a perfect birth, she believes there’s a doula for everyone.

“If you want an Asian doula, there are Asian doulas,” Davis says. “If you want a free doula, there are tons of free doulas. If you want a trans person, there’s trans doulas. There’s literally a doula for everyone.”

Part of Davis’ appeal to clients is her intersectional identity as a black, gay, Jewish woman. She says she has shared the same experiences that queer parents face and recognizes the fears some women of color have about maternal health, which can make her clients feel safer.

It also means there’s less time spent on questions about culture and understanding nuanced identities with her clients: “You don’t have to explain it. It allows us to just get to work,” Davis adds.

For first-time parents Nicole and Eddie Minkoff, they wanted someone they could feel safe with. Friends advised them if you could only afford birthing classes or a doula, get a doula.

Nicole Minkoff suffered from all-day sickness during her pregnancy which worried her about giving birth — would it be long? What if there were complications? But Minkoff says Davis alleviated her angst.

“I remember how safe and comfortable I felt with her,” Nicole Minkoff says. She and her partner knew Erika Davis through the local Jewish community and decided to have her as both their birth and postpartum doula, a relationship that involved working together for five months.

In May, Nicole gave birth to a baby boy: six pounds, 12 ounces.

Eddie says whenever he got nervous during the birth, he would turn to Davis and she would respond with a giant grin.

“She was supportive, and also just like a rock,” he said.

Davis and her wife imagine having two kids, sometimes even four. But it’s been a difficult process. Fibroids and other personal health issues have been a hurdle.

Two years ago, she walked into her doctor’s office for a prenatal check up only to be told there was no heartbeat.

Doctors suggested waiting and letting her body process the miscarriage but Davis didn’t want that. She had the fetus removed through a process known as D&C, dilation and curettage. The process ended up taking several visits because of complications.

“From the doctors saying there’s no heartbeat to the end was the worst month of my life,” Davis remembers. “It was awful.”

For Davis, the miscarriage was hard. No one seemed to be talking about it, despite research showing that miscarriage happens in one in four pregnancies. But data is hard to pinpoint. Many times, women don’t report their miscarriage and how data is collected varies by counties and states.

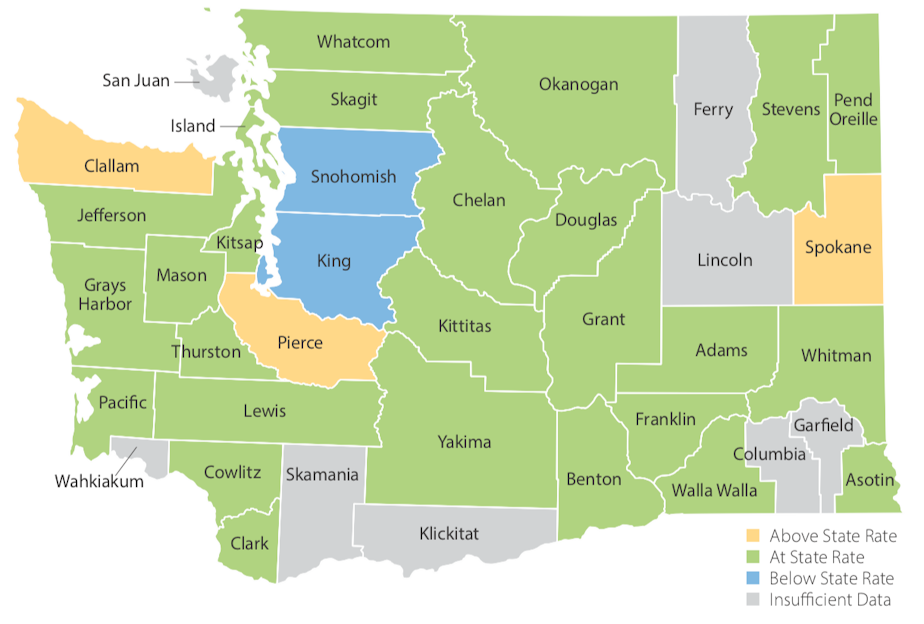

While Washington as a state has one of the better maternal outcomes in the U.S., when the data is broken down by race, disparities appear.

According to a report by the Washington Department of Health, African American and Native mothers have twice the infant mortality rate of their white counterparts. For every thousand births, nearly nine African American babies die. For American Indian and Native babies, that rate is 8.4. White babies have the lowest mortality rate in the state at 4.2 deaths.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also finds that nationally, black women have 3 to 4 times more pregnancy-related deaths than white women.

For Davis, those statistics are unacceptable. She wants to center her work around helping other black women bring babies into the world safely and respectfully. “Being a doula allows you to see their humanity,” she adds.

Davis’ services are booked straight through the year.

In fact, her doula bag is already packed and in her car. This weekend, she’s waiting for the call — the one that says the baby is coming.

She’s got all the essentials: massage rollers for aching muscles, aromatherapy oils to relax the senses, hair ties and a fan to cool off mom.

“It’s so nice to hold a fresh baby,” Davis says with a laugh.

This story was produced by Esmy Jimenez as part of the Next Generation Radio Project, a week-long digital journalism training project designed to give competitively selected participants, who are interested in radio and journalism, the skills and opportunity to report and produce their own multimedia story. Those chosen for the project are paired with a professional journalist who serves as their mentor. KUOW hosted the project in July 2018.