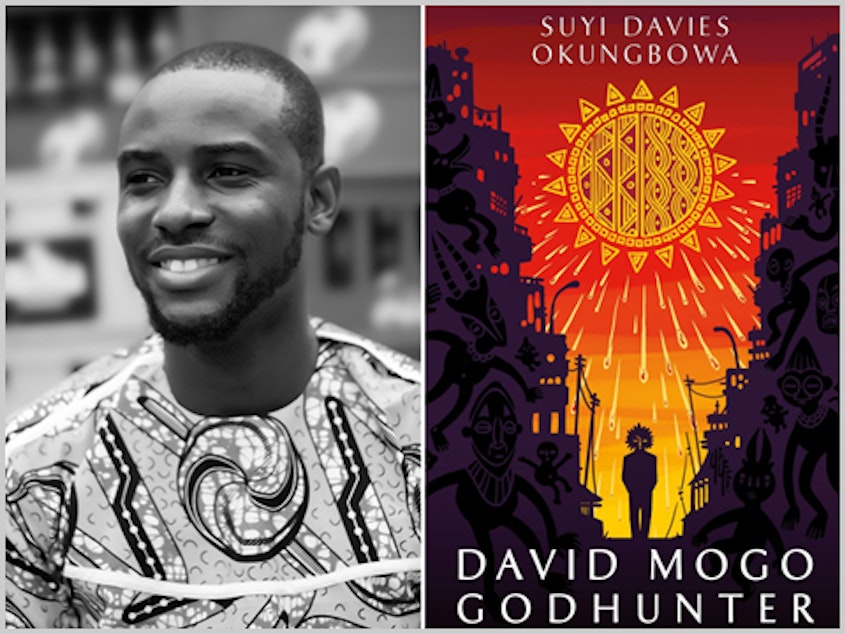

Suyi Davies Okungbowa on the spirit of Lagos and the changing faces of fantasy

In the author's new book, gods fall from the sky - and a young demigod comes into his own.

You’re clicking through Craigslist looking for work, when you see a posting for a… godhunter?

It’s the ultimate freelance gig – “helping people get deities out of places they’re not supposed to be,” says author Suyi Davies Okungbowa. The side hustle lends its name to his new novel: David Mogo, Godhunter.

Suyi Davies Okungbowa: David Mogo, Godhunter

Record producer Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong speaks with Nigerian author Suyi Davies Okungbowa about his first novel, David Mogo, Godhunter.

These gods shouldn’t be in the city at all, but after an event called The Falling, Nigeria’s largest city Lagos has been inundated with new celestial residents. A demigod named David Mogo who’s been there all along, neither deity nor man, becomes a godhunter. (Catch and release, of course: job security.)

When he’s hired by a shadowy figure to catch two very big fish, things become… interesting.

Lagos is very much a character in the book. “I like to think about Lagos as a city that has a spirit,” he says with a laugh. “I say spirit and not soul, because a soul is more like a thing you can connect with. But a spirit is something that possesses.”

The city is fast, loud, and powered by Nigerian pidgin. The book is full of it, and Davies Okungbowa chose not to translate or italicize it. “If I had to look up words from Harry Potter, then you can look up words in my pidgin,” he says.

But it was also a question of audience. The book was written for a Nigerian audience rather than the Western gaze, and it shows. Richly layered context is built on an assumed familiarity with the gods.

Davies says it was important for him to use an African pantheon because of the ubiquity of Greek gods, Norse gods. “I was like, ‘but I know about all these cool gods that I grew up knowing, that I was told stories about. Why aren’t they out there? They’re just as cool, if not even cooler.’” So in the spirit of Toni Morrison, he wrote the book he wanted to read.

That raised the question of what would make the book feel like fantasy to wider audiences. Science fiction is always a form of exoticism, he says – which is something Africa is quite used to. “It’s a tricky thing: how much of this is deemed exotic because it is itself, or because it’s fantastic?”

This is another reason it’s important to him that his work be accessible to the people it’s written from, rather than packaged for others to devour. He’s writing against a day when pidgin is as unremarkable a draw as Russian or Italian, and a book’s fantastical nature will speak for itself.

David Mogo is half god, half human, and not quite sure where he fits. When pushed to discover the parts of himself that are not just god hunter, but god, he struggles to reconcile them with who he’s always been told to be.

Davies Okungbowa, himself a middle child and “middle person” who counts Lagos and Tucson alike as home, has had similar struggles. He reconciles them by realizing that even if you don’t belong to a place, you will always belong to yourself.

“I think that’s what ends up happen for people who are patchwork persons,” he says. They have to decide what their definition of themselves really means in the end, and then just hold onto that.”