So you think you know all about the plague?

The bubonic plague has cropped in the state of Oregon for the first time in nearly a decade.

This time a person likely caught it from their cat, health officials in the central part of the state said last week. Doctors identified the disease quickly and treated the person with antibiotics. They also tracked down all the person's contacts (and the cat's contacts) and gave them medication as well. So they don't expect the disease to spread or cause any deaths.

Most people know the basics about the plague.

They know that, in the 14th century, it caused the Black Death – the pandemic that may have killed 30% to 50% of the population in parts of Europe, with an estimated death toll of at least 50 million. And they know that it spreads through rodents – and the fleas that bite them.

But over the last decade, scientists have learned way more about the plague and how our bodies respond to it. Here are a few plague revelations.

People of European descent may carry a gene (or two) that protects them against the plague.

When the Black Death spread through Europe and the United Kingdom back in the 1300s, the disease changed more than society: It also likely altered the evolution of people's genome.

A study, published in 2022, found that people who survived the plague in London and Denmark had mutations in their genomes that helped protect them against the plague pathogen, Yersinia pestis.

Altogether, the researchers found four helpful mutations in people's genomes. The advantage was quite substantial. One mutation boosted people's chance of surviving the plague by 40%, the study estimated. That's the biggest evolutionary advantage ever recorded in humans for a single mutation, researchers told NPR.

Survivors passed those mutations onto their descendants, and many Europeans – and Americans of European descent – still carry those mutations today.

But these helpful genes have likely come at a cost. One of the mutations increases a person's risk of autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn's disease.

After decades of silence, the plague can re-emerge in a region

Each year, the world records 200 to 700 cases of plague, although many cases likely go undetected. Most of these cases occur in hotspots around the globe, such as Madagascar, which accounts for about three-quarters of global cases. The U.S. typically record fewer than a dozen cases each year, with most of them occurring in the west.

But really, Y. pestis can crop up almost anyway, even in places where scientists think they've eradicated the disease or haven't seen it in decades.

That's exactly what happened in Libya. After no record of plague cases for 25 years, the disease appeared again in 2009. At first, scientists thought perhaps somebody – or an animal – had brought the pathogen in from a neighboring country. But when they decoded the bacteria's DNA, it revealed a surprise: The plague in Libya most closely resembled Y. pestis that originated in Central Asia thousands of years ago (and didn't look like the bacteria found in a neighboring country).

"We think the plague is extinct in these places, but it's not," microbiologist Elisabeth Carniel at the Institut Pasteur told NPR. "The plague is still there."

So where is it hiding? It's likely circulating, undetected, in rodents and the fleas they carry. Maybe the bacteria is at such low levels that it goes undetected for decades.

Even when antibiotics are available, one form of the plague can have an extremely high fatality rate

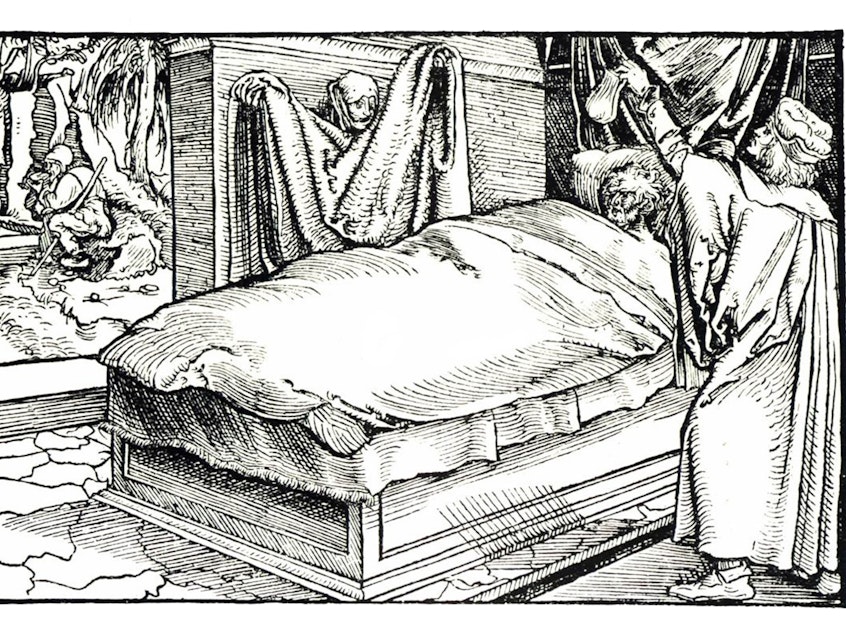

The plague comes in several versions, depending on which body part the bacteria invade. When a flea bites a person, they typically develop what's called bubonic plague. In this case, the telltale sign is one or more swollen and painful lymph nodes, known as buboes. (The word "bubonic" comes from the Greek boubon, which means groin, because some people have swollen lymph nodes in their groin). Doctors can diagnose the disease by taking a sample from the person's blood or their lymph nodes and then submitting it to a lab for testing.

But when the bacteria spread to the lungs, it can cause what's called pneumonic plague. In this case, there's often no telltale sign of the plague, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This version is much more dangerous, says entomologist Adelaide Miarinjara at Emory University. "It transmits pretty easily between people because it spreads through droplets, almost like COVID spreads."

And people can die more quickly with pneumonic plague, she adds, because the disease progresses more rapidly. "The key here is early diagnosis. If people aren't expecting it or don't seek treatment, they can die."

In 2017, Madagascar suffered a large outbreak of pneumonic plague, when a person from a rural part of the country brought the disease to the coastal capital of Toamasina. That city hadn't seen a case of the plague in nearly a century, says Miarinjara, who was in Madagascar at the time. "A person transmitted the disease on public transportation," she says.

The country recorded more than 2,400 suspected cases, including nearly 1,900 cases of pneumonic plague. One study estimated that about 25% of people with confirmed cases died in this outbreak.

Plague bacteria make fleas vomit

In the western U.S., all sorts of rodents can carry the plague, including chipmunks, squirrels and prairie dogs. And they can transmit the bacteria to humans through bites and scratches. (When I was in college in Pasadena back in the early 1990s, a classmate caught the plague from a squirrel she was feeding.).

But most of the time, rodents – and often people – catch Y. pestis from a flea bite. And scientists now have a detailed understanding of how the flea transmits the bacteria during this bite.

When a flea itself is infected, the plague bacteria lives inside the insect's gut. There, the bacteria create this gooey, sticky material, called a biofilm. This film forms a little plug in the flea's throat, making it hard for the insect to swallow. So when the flea bites an animal, instead of swallowing the animal's blood, the flea essentially vomits the biofilm - and the plague bacteria – into the animal's blood.

"You can imagine, you have something stuck in your throat and you try to take in some water but can't. You will vomit all that water out, and that's what happens to the flea," microbiologist Viveka Vadyvaloo told the Washington State University Insider back in 2021. "The blocked, starving flea will repeatedly bite its rodent or human host, creating more opportunities for infection."

The Black Death gave rise to the word quarantine

The idea of isolating, or quarantining, sick people dates back at least to 3,000 years. The book of Leviticus in the Bible mentions how to isolate people with leprosy.

But the word "quarantine" itself arose during the Black Death, when the city-state of Dubrovnik, now part of the country of Croatia, enacted what is likely the first state-imposed isolation.

At the time, Dubrovnik was a wealthy merchant city along the coast of the Adriatic Sea. City leaders wanted to keep the bubonic plague out. So they began to force visitors to wait for 40 days on a remote island, outside the city, before coming ashore.

They called the wait quarantino, from the Italian word for "40."

"The first quarantine was pretty much improvised," said Ivana Marinavić, who heads the educational programs at the Lazarettos of Dubrovnik, the first buildings ever constructed for the sole purpose of quarantining.

If you broke the quarantine during the plague, the consequences were severe. "Torture, or cutting your nose or your ears off," Marinavić told NPR. [Copyright 2024 NPR]