So the doctor says you have dense breasts. Now what?

When Olivia went in for her mammogram last month, she received unexpected news: she had “extremely dense breasts.”

“I had never heard of this,” said Olivia, who is 50 and whose name has been changed for her privacy. “I didn’t understand it.”

She had expected to hear that something was wrong, or that everything was fine, but this didn’t fit either category.

“Is this something I should worry about or not?” Her doctor didn’t know, either.

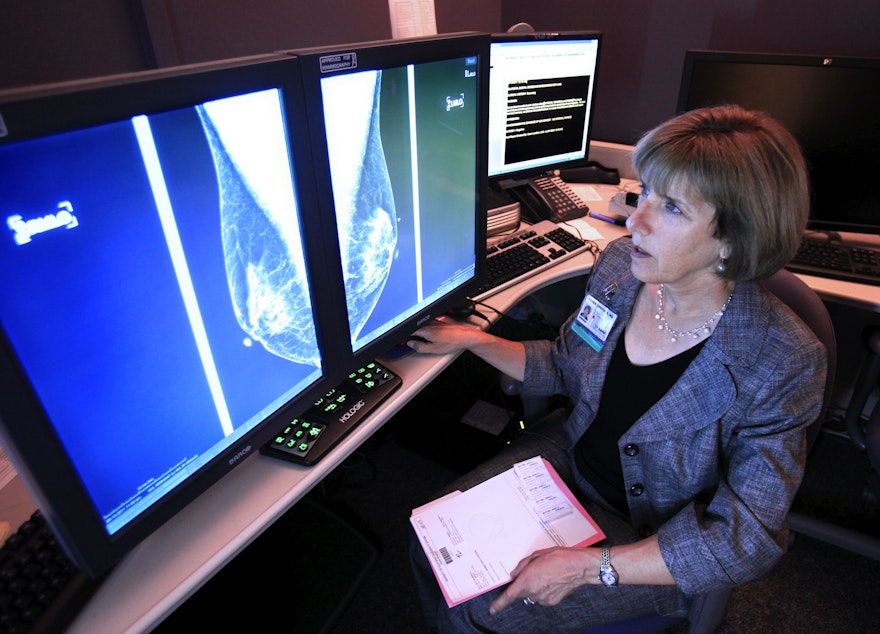

You cannot tell if you have dense breasts by their appearance, or the way they feel. Breast density is a classification a radiologist gives based on the breast’s appearance on a mammogram. Density is a measure of how much fibrous and glandular tissue is present in a breast, which appears white on a mammogram, compared to fat in the breast, which appears black.

Suspicious lesions are also white, so having more fibrous or glandular tissue (“denser breasts”) makes it harder to find growths that could be cancer. It also increases your lifetime risk of breast cancer, though not your risk of dying from it.

Recently the Food and Drug Administration ruled that mammograms should include information about breast density.

In an email, the FDA told me that “knowing their breast density will empower women as they make health care decisions, including determining if additional screening is needed.”

But many doctors and researchers warn that we do not have good guidelines about what to do if a woman has dense breasts, and reporting this information is more likely to cause lead to harm — from more imaging, out of pocket costs, unnecessary biopsies, and even unnecessary chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery for women who don't have cancer — than to save lives.

Olivia, who coaches medical professionals on working better in teams, asked several physicians what to do, but none had a satisfying answer.

“I asked the radiologist what she would do if she had breasts like mine," she said.

The radiologist suggested getting an annual screen, but “it didn’t feel like real advice," Olivia said. "What I read between the lines was, she would be scared if she had breasts like mine.”

I asked Olivia if she felt empowered knowing that she had dense breasts.

“Well, right now, I don’t know what this means, so I just feel confused," she said. She also wondered how other women would process the same information.

"I’m university educated, I don’t have a family history [of breast cancer], and I’m not a big worrier,” she said, “I still don’t know what this means."

Breast cancer screening has been controversial since I began studying medicine 11 years ago.

In my second year of medical school, an independent research body ignited a firestorm when they advised that most women did not need mammograms until the age of 50 (a stance that most organizations have since adopted). Self breast exams and clinical exams by a doctor also fell out of favor before I graduated, even as some doctors and advocacy organizations continue to forcefully recommend them.

Like those earlier clashes, the controversy over whether to diagnose and report breast density illustrates fundamental conflicts over the purpose of screening programs, and who and what should be driving them.

Kenny Lin, a family medicine doctor at Georgetown, told me, any screening test can potentially help or hurt the people we screen.

In the case of breast cancer screening, around 1 in 10 women screened for breast cancer will be told that they have a suspicious mammogram finding that turns out to be normal.

These false positives lead to unnecessary anxiety and, sometimes, unnecessary procedures, like needle biopsies.

While it may be easy to dismiss anxiety as an insignificant price to pay, Lin does not see this as insignificant.

“Patients who have had biopsies, even when they’re told everything is okay, they’re never completely reassured,” and may remain convinced that something sinister is lurking in their bodies.

More alarming is the risk of "overdiagnosis," or finding and treating breast cancers that would not have been life threatening.

While it’s impossible to tell which individuals did and did not benefit from treatment, researchers estimate that up to one in three people diagnosed with breast cancer through screening would have never developed symptoms from the cancer.

This means that men and women with breast cancer may have surgery, hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, and radiation that did not prolong and even potentially shortened their lives.

These kinds of cancers are mostly picked up on screening, Lin says, “because a cancer that doesn’t spread or cause problems wouldn’t be found unless we do a test to look for it.”

The more screening tests like mammograms and ultrasounds we do, the more cancers we will pick up that never needed to be treated.

Another risk of screening mammograms is missing a diagnosis, or a "false negative." Women who are told that their mammogram was normal may even dismiss their own symptoms, potentially delaying a cancer diagnosis.

For women with dense breasts, the risk of a missed diagnosis on mammogram is high.

While mammogram misses around 13% of cancers in women with non-dense breasts, it misses 37% in women with dense breasts, while also more frequently misdiagnosing benign findings as potentially cancerous. For that reason, advocates say women with dense breasts cannot rely on mammograms alone.

One of the most important advocates in the push to include breast density was Nancy Capello, founder of the nonprofit Are You Dense, who died of complications from breast cancer treatment last year.

Capello was diagnosed with breast cancer at her doctor’s office, six weeks after a normal mammogram. She later learned that the mammogram showed that she had dense breasts, and may have prevented her diagnosis. She felt the information had been concealed from her, and that she and other women should know if they have dense breasts.

“I call it the best-kept secret--but it WAS known to the medical community,” she wrote on her blog.

She and her husband started a campaign to change mammogram reporting in their home state of Connecticut.

“We started this advocacy 15 years ago, when Nancy was diagnosed with stage 3C breast cancer after 11 years of normal mammograms,” her husband, Joseph Capello, told me. “If Nancy had gotten an ultrasound she may be alive today.

“What began in our spare bedroom in New Hampshire is now federal law,” he continued. “My heart’s broken because she’s gone, and so are thousands of other hearts. The least I can do is carry on her work.”

I asked Joseph Capello about potential harms of more screening.

“I can’t imagine what potential harms there would be,” he said. “People don’t die from needle biopsies, they die from missed diagnoses… If you have dense breasts, you need to get an ultrasound. I don’t care what your doctor says. If your insurance doesn’t pay for it, you pay for it.”

It is estimated that if one thousand women with dense breasts had an ultrasound, we would find two more women with breast cancer. But so far, there is no good data to suggest that routinely doing more imaging tests in women with dense breasts would save lives.

Additional screening, like ultrasound, increases false positives, leading to 40 more needle biopsies for every thousand women screened. But how do you balance the risks of false reassurance, unnecessary biopsies, and unnecessary breast cancer treatment with the possibility of saving women, even one woman, from dying of breast cancer?

For Lin, this is not a theoretical question, but a deeply personal one. He remembers the first patient he diagnosed with breast cancer a few months after she had had a normal mammogram.

“I had just started as an attending,” he told me. The patient “came in with a breast lump, and when I examined it, I knew it was a cancer. I remember she was shocked, because she thought she was in the clear, because the mammogram had been normal.”

“I could have said, because of that, that everyone should have gotten supplemental screening. But I don’t think that would have been the right thing. I think I would have caused more harm than good.”

Like anybody else, doctors, nurses, and physician assistants are affected by bad outcomes, and this can lead us to overcorrect with future patients, ordering tests that may not be in their best interest. But for Lin, the bottom line about additional screening for women with dense breasts is that “we don't know if it improves breast cancer outcomes or only leads to more anxiety, more biopsies, and more overdiagnosis.”

“The natural reaction to being told that you have dense breasts is, ‘What other tests can I do to find the cancer?’" he said. "That’s a natural reaction, but maybe not a logical next step, because we don’t know what the next logical step is.”

As a primary care doctor, I do not find the data that additional imaging would benefit women with dense breasts compelling, and the FDA did not provide me with any empirical evidence to support this claim. But when talking to patients, stories are almost always more powerful than data. It’s hard to tell a patient that they shouldn’t get another test, because what if they’re the one patient who could benefit?

I carry stories of missed diagnoses, and I carry stories of harm. I remember one of the first patients I ever talked to about breast cancer screening, a woman who cleaned houses and had no health insurance. She had a mammogram in a mobile van run by a local advocacy organization in Atlanta. I was a medical student at the time, sitting with my mentor as we reviewed the images in a darkened exam room with the patient. We showed her the large tumor, probably a cancer.

“I can’t afford the biopsy,” she said, staring off into the distance, more to herself than to us. It was several hundred dollars in a state where most poor people still don’t have access to insurance.

“I just can’t afford it,” she said, shaking her head, her face lit by the screen.

That moment serves to me as a reminder that a screening test is only helpful if physicians can respond thoughtfully to a positive result.

When physicians or organizing bodies make recommendations to patients about screening tests, it should be something that on the whole is more likely to benefit than harm the individual. It doesn’t seem that dense breast reporting cleared that bar, even though the FDA told me they were “not aware of any potential harms.”

The advocacy seems to have outpaced the science. I hope the science will catch up. For now, patients and physicians are left to work through the murky data, while we await better information.

Lin believes physicians and advocates could better communicate the limitations of screening mammography.

“Screening tests are not like immunizations,” he said. “We think if we get a mammogram, you should not get breast cancer, just like if you get a measles vaccine you should not get measles. But screening tests are limited tools. You should always trust your own perception of your body, and see your doctor when something isn’t normal.”

In fact, about half of breast cancers are diagnosed because women themselves notice changes in their breasts. A recently normal mammogram does not mean such changes can be safely ignored.

I believe we should communicate to patients that breast density is a spectrum of normal, and not a pathological state. Breast density is not a worrisome finding, but one more piece of data.

We should use emerging research to educate both primary care physicians and radiologists about how to incorporate data about breast density with an individual woman’s risk of breast cancer when deciding if she needs more tests.

For example, a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggested that if a woman with moderately dense breasts had a greater than 2.5% calculated risk of developing cancer over the next five years, or extremely dense breasts and greater than 1.0% risk, supplemental screening is probably in her best interest.

In the future, such a holistic approach to screening recommendations would minimize confusion and harms, instead of leaving patients and their physicians to navigate concerning reports without any thoughtful guidance.

In my practice, I leave the final choice to the patient, but remind them that screening is for women without symptoms.

Even if your mammogram was normal, trust your body. No test is a substitute for your intuition.

Elisabeth Poorman is a primary care physician and writer in Seattle.