Six more women accuse David Meinert of sexual misconduct—and assault

1 of 4Elise Ballard poses for a portrait on Monday, August 6, 2018, at her home.

1 of 4Elise Ballard poses for a portrait on Monday, August 6, 2018, at her home. S

ix more women have come forward with allegations of sexual misconduct and assault against David Meinert, the Seattle nightlife entrepreneur.

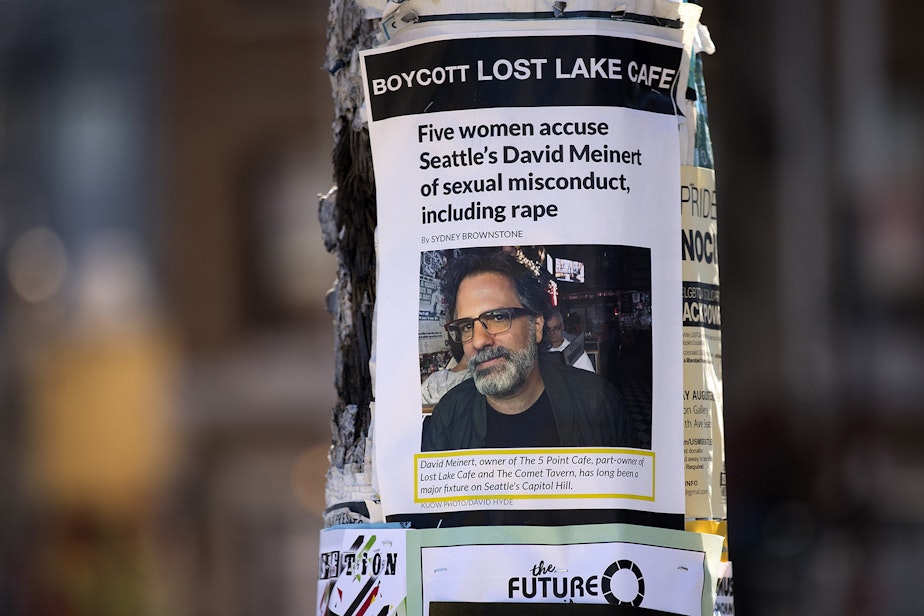

These women contacted KUOW after reading an earlier story about Meinert, in which five other women had accused him of sexual misconduct, including sexual assault and rape.

Read more: Five women accuse Seattle's David Meinert of sexual misconduct, including rape

The addition of these women’s stories makes 11 accusers total. They span the years 2001 to 2015.

All six women are using their full names in this story. None reported their stories to police.

Several of the newest accusers are well-known in the music and creative communities: Eryn Young, a musician, Bethany Jean Clement, food critic at the Seattle Times, Elise Ballard, founder of catering company Umami Seattle, and Rebecca Jacobs, board chair of Urban Artworks, a nonprofit that provides opportunities for court-involved youth.

Jacobs is also copy director at The Hilt, the creative agency of Strategies 360, the same public relations and crisis communications firm that Meinert hired last year to respond to the allegations.

Maria Leininger is a political operative and adjunct professor at Bellevue College.

Jenna Jane McMaster works in communications.

Meinert did not respond to more than 50 questions about the allegations made by the newest accusers, despite multiple attempts to reach him. Strategies 360, which represented Meinert during the reporting for KUOW’s first story about Meinert, dropped him as a client after learning one of their employees had come forward to accuse Meinert of sexual misconduct.

The same day that KUOW contacted Meinert about the newer accusations, Meinert’s Facebook page was deactivated. Two days later, Guild Seattle partner Joey Burgess announced that Meinert no longer held a stake in Lost Lake Café and Lounge, The Comet Tavern, Grim’s, or restaurant group Guild Seattle.

‘In front of a room full of people’ (2004)

Eryn Young said that she saw Meinert often in the early 2000s. She played in several music and dance projects and performed at On the Boards, a theater in Queen Anne. Meinert was an acquaintance, she said.

Young said she, her husband Tim Young, and several friends attended a music show at the Mirabeau Room, a club Meinert used to own, on August 5, 2004.

They stayed for a DJ set, which turned into a dance party. Young left the dance party, she said, heading to the bar for drinks.

Meinert was at the bar, and they started to chat. Then, mid-conversation, Young said Meinert reached under her skirt and inserted his finger into her vagina. Her husband was in the next room.

Resources for victims and survivors of abuse:

- King County Sexual Assault Resource Center: 888-998-6423 // Hotline for therapy, legal advocates and family services

- UW Medicine Center for Sexual Assault & Traumatic Stress: 206-744-1600 // Hotline, resources including counseling and medical care

- Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs // List of providers across the state that offer free services.

- Rape, Abuse, Incest National Network (RAINN): 800-656-4673 // Hotline and/or online chat with trained staff

Young froze, so shocked she didn’t move. Meinert, she said, removed his hand and said, “Oh, you’re wet. Did you come?”

“I said, ‘I've been dancing, I'm probably just sweaty,’ and I walked away,” Young said. She collected her things and left quickly with her husband.

“I felt disgusted, and guilty, I guess,” Young said. “I was standing there, just getting drinks in an open space. And I guess I felt falsely protected by the fact that my husband was right there in the next room. I just felt humiliated.”

Young told a friend who was at the club what happened. That friend, Ivory Smith, confirmed this to KUOW. Smith advised Young not to tell anyone, including her husband.

Smith told KUOW that her friend was worried that her husband would get angry if he knew—and possibly confront Meinert. Also, she said, they ran in the same circles. Meinert managed bands that included their friends.

Young worried about retribution.

“Men lie and they try to publicly humiliate women when they tell people,” Smith told KUOW. “I stand by [advising her not to say anything] because I do think it would have caused her more pain if she had said anything about it.”

Young eventually told her husband. Tim Young said his wife shared her account last year. She told him she was ashamed for not having told him earlier; she said she was too embarrassed at the time.

After reading KUOW’s story last month about the allegations of five other women—and Meinert’s claim that he had never raped anyone—Young decided to speak out.

“He did that at a bar,” Young told KUOW. “Standing at a bar, in front of a room full of people. And it was so casual.”

After the piece published, Ivory Smith contacted Young, this time with a different message: Say something.

Now, Young said, she has nothing to lose. “And nothing to gain,” she added. “Except for hopefully empowering other people to say something.”

‘So much of this stuff happens to all of us.’ (around 2006)

Before she went to work for the Seattle Times, Bethany Jean Clement was managing editor for Seattle alternative newspaper The Stranger. Before being hired full-time, she freelanced for the newspaper, which is when she met Meinert.

One night around 2006—she wasn’t sure of the specific date—Clement threw a party at her Capitol Hill apartment. Meinert and several Stranger staffers attended. At the end of the night, after everyone else had gone home, Meinert lingered, Clement said.

She said she was going to bed, and he left.

Shortly after he left, she said she heard a knock on her side door. Clement said she went to answer, and there was Meinert. “He just grabbed me and started kissing me,” Clement said. In an instant, she said, he had pushed her onto the floor in the entryway, his body on top of hers.

“It was just incredibly fast,” she said.

When she realized what was going on, Clement said something to the effect of “No, this is not happening,” and he stopped. She remembered him explaining himself: “Oh, I had to come back and try.”

Clement told Erica C. Barnett, then a reporter at The Stranger, the next day. Both recall Clement telling the story in a joking way. Clement said laughing it off was her way of coping.

“That’s how we as women are taught to deal with these kinds of situations,” Clement said. “And I think as women, we’re taught to feel lucky if it isn’t worse.”

Clement said the incident didn’t traumatize her then; it didn’t occur to her to tell more people. It’s only now, looking back and hearing the other stories, that she sees her story in the context of something bigger. Her hands shook as she shared her account with KUOW.

“I guess I was sadly not surprised,” she said. “I just brushed it off—as one did back then.”

‘He knew he had fucked up. He was telling me to shut up’ (2003 or 2004)

Rebecca Jacobs was promotions manager at The Crocodile music club in her early 20s, and she and Meinert crossed paths frequently. They had mutual friends, and a few years later, after she moved on to another job, she and Meinert were set to meet with one of those friends at the Mecca Café.

That friend never showed, so Meinert offered Jacobs a ride to the friend’s house, she said. At some point, Jacobs said she noticed they weren’t headed to the friend’s house. Instead, she said Meinert drove her to his own house and parked in his garage.

At that point, Jacobs said, Meinert took out his penis. He pulled her hand over toward his lap and put his hand on the back of her head.

“It was shocking,” Jacobs said. “I don’t remember feeling scared.”

Jacobs said she made an excuse to get out of the situation and was able to leave.

Still, Jacobs blamed herself: “When you’re a young woman and you find yourself in a situation like that and you’ve had some drinks, you think you bear some responsibility.”

Jacobs told a couple of friends about it at the time, she said, but didn’t think more of it until Meinert showed up to The Showbox, where she was working the door.

“He said, ‘You’ve got a big mouth, don’t you?’” Jacobs said. “And I just felt sick. ‘You like to talk and you should shut your big mouth.’”

The message, Jacobs said, was clear.

“Whatever Dave wants to say about other misinterpreted moments, it’s pretty clear to me now—it was pretty clear to me then, that he knew he had fucked up,” she said. “He was telling me to shut up. So I did.”

Jacobs said she didn’t want to miss opportunities working in Seattle’s music and arts scene and worried Meinert would “ruin” her if she said more.

Jacobs started dating her husband, Chris Jacobs, general manager at Sub Pop Records, nearly a decade later who confirmed to KUOW that Jacobs told him the story about Meinert several years ago.

“The initial, I don't know how to characterize it, exposure, interaction, while sounding real stupid and clumsy and creepy, was less alarming to me than the follow-up,” Chris Jacobs said. “Which sounded super troubling.”

Still, the Jacobs maintained friendly, professional contact with Meinert in the years following the alleged incident.

That’s partly why Jacobs is talking now. In KUOW’s previous story, Meinert used a friendly relationship with another accuser as evidence that nothing serious or disturbing had happened between them.

“That’s a fallacy that if you remain cordial, acquainted, even friendly with someone who was aggressive or harmed you in some way that it negates somehow that it happened,” Rebecca Jacobs said.

She freely acknowledged that she had congratulated Meinert on the opening of Big Mario’s and had collaborated with Meinert on a fundraiser for King County Executive Dow Constantine.

“It doesn’t change that it happened,” Rebecca Jacobs said. “I know of women who have been in positions like this, where it’s a small town, small circles, so you just play nice, and you move on.”

‘I didn’t say anything at all,’ (2003 or 2004)

Elise Ballard, the founder of catering company Umami Seattle, said she was working at the Center on Contemporary Art when she volunteered to set up a kiosk at the Capitol Hill Block Party, then run by David Meinert and Marcus Charles, a bar and restaurant entrepreneur and friend of Meinert.

Ballard was working with Meinert at the 2003 or 2004 Block Party, she said, when it came time to break down the kiosk at the end of the event around 2 a.m. She and Meinert dragged tables from the kiosk into the Center on Contemporary Art space, then located on 11th Ave.

Once Ballard and Meinert had moved behind a wall that blocked the view of the door, Ballard said he began kissing her. It was consensual, she said, at first. But quickly and forcefully, she said, he turned her around, and inserted himself into her. “It was fast and furious,” she said. And over in a minute.

“I didn’t protest, I didn’t stop him,” Ballard said. “I didn’t say anything at all.”

She was in shock, she said. “Really, it was so fast and strange.”

Ballard said she didn’t consent to sex, but added that times were different—and that Meinert may have interpreted the absence of a “no” as a “yes.” She was embarrassed and ashamed, in her words, that she “let it happen.”

In the wake of #MeToo, what constitutes consent to sex—and what it means to violate consent—has received renewed attention.

In some states, rape is prosecuted only when force has been used, or the victim is underage or unable to agree to sex.

Four U.S. states—Montana, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin—require that individuals consent to sex, either by saying yes or using physical cues. This is known as an affirmative consent standard.

In Washington state, however, victims must prove there was a “clear lack of consent.” What this means depends on the prosecutor. Some might want proof of fighting, or a witness to have heard screaming.

But victims of sexual violence don’t always fight or scream, said Riddhi Mukhopadhyay, legal director at the YWCA’s Sexual Violence Legal Services. Many remain still and say nothing—a “freeze” response that can be seen as “complicated” by the criminal justice system, Mukhopadhyay said.

“I don’t think the criminal justice system takes [freezing] into account because it’s also based on the old ideas of what rape looks like,” Mukhopadhyay said. “Somebody has to be crying or scratching or saying ‘no, no, no,’ when the reality is people are freezing because their brain can’t even process what’s happening or they are having fear around what’s happening.”

Ballard told her ex-husband about the alleged encounter with Meinert but said she didn’t tell him the whole truth. Todd Gilbert confirmed that Ballard told him about Meinert making a pass at her that night, but nothing more.

Ballard said she thought she had put the experience behind her. But last year, during the conversations about #MeToo, Ballard started telling more people her story.

Ballard’s boyfriend, Jeff Fernald, told KUOW that she told him her account of what happened with Meinert after the couple ran into him at the Upstream Music Fest in June.

“I felt like she downplayed it the first time she told me,” Fernald said. “There was a lot of shame that went along with it.”

‘I was very aware that he and I were trapped in the SUV’ (2015)

Maria Leininger, a lawyer and account executive at political consulting firm Moxie Media, said she met up with then-state senator Cyrus Habib (now Washington state’s lieutenant governor) and others, including Meinert, for drinks on election night in 2015. The group headed to Big Mario’s for pizza and ordered an Uber SUV to fit them all.

Leininger, who said she had met Meinert that evening, ended up sitting in the back row, next to him.

“When we were driving over to Big Mario's he was saying, ‘You should blow me,’ and, ‘We should hook up,’” Leininger said. “I was doing the normal nervous laughter thing.”

Leininger said she tried to manage Meinert this way while trapped in the back seat, but at one point, he grabbed her head and started pushing it into his lap.

Recalling the night, Habib, who is blind, said he couldn’t hear precisely what was going on in the back seat, but sensed something may have been off. He texted Leininger to ask if she was okay.

Leininger said Meinert saw Habib’s text and backed off. She texted Habib back and told him there was no problem, but later told him what happened.

"The way it was portrayed was he was being gross," Habib said. "I was unhappy and disappointed that he had acted in an inappropriate way with someone he had recently met."

Kristina Brown, Habib's political coordinator, was also in the SUV, but said she was distracted by a conversation with the person sitting in the front seat and didn’t notice anything going on behind her. Still, she said she had noticed Meinert making “inappropriate comments” (she couldn’t recall what, exactly) before getting into the SUV.

“I just remember having a general feeling of, ‘Oh, this guy is trying to come off as a slightly shocking party boy,’” she said.

‘I got another slap in the face’ (2014)

Editor's note: The original version of this story included only Jenna Jane McMaster's first name. She has since decided to come forward with her full name.

Jenna Jane McMaster was a 24-year-old PhD student at the University of Washington, studying philosophy and earning a $1,600 monthly stipend. She aimed to make ends meet in the service industry—not at one of Meinert’s establishments—but was depressed and spent many nights studying or drinking at The 5 Point Café, which Meinert owns.

Meinert, then 48, conducted meetings at the end of the bar, McMaster said, and over time, began sending her high-end whiskeys. He asked her about her studies, which she thought friendly, but wasn’t interested in a man more than 20 years her senior.

One night, McMaster said, she came to The 5 Point after a frustrating evening training servers and earning no tips. Meinert sat next to her, she said, and she complained to him about her financial woes and the service industry. She said he got her a whiskey.

“I didn't think that he was trying to come on to me or anything,” McMaster said. “It seemed like he was interested in being my mentor or something.”

McMaster expressed interest in being a bartender, and she said Meinert told her he could get her hired in some capacity at Lost Lake Café and Lounge, then Meinert and Guild Seattle’s 24-hour diner on Capitol Hill. McMaster said she told Meinert that would be a dream come true, and she said he suggested they go to a whiskey bar so he could teach her more about expensive liquor.

McMaster agreed, and they drank at a bar downtown. Soon, though, she said she felt too drunk to stay out and said she was going home. Meinert insisted on walking her to her Belltown apartment, she said.

On the walk, McMaster said that Meinert told her they needed to stop at another bar where she could meet an “industry person” who could help get her work. They stopped in at another bar and had another drink. McMaster said she told Meinert again that she had to go home.

Meinert walked McMaster the rest of the way, but when they arrived, she said he tried to kiss her. She said she pushed him away, but he pushed her up against the brick façade of her building, pinning her arms behind her. He was forcibly kissing her then, she said, and sticking his tongue in her mouth. McMaster struggled and pushed him away again.

And then, she said, he slapped her.

“I was yelling ‘What the fuck, get off of me!’” McMaster told KUOW. “But he was playing it off like it was a sexy thing. It was like he was trying to play a sexy game, like it's all a joke. And I was like, ‘No, seriously what the fuck.’”

McMaster tried to get into her apartment building at that point, but he tried to come inside, too, she said. She declined, still trying to be somewhat polite—she wanted that bartending job—but he kept trying to press himself inside. She decided to step outside again to finish the conversation.

At that point, McMaster said, Meinert pushed her against the wall again and stuck his tongue in her mouth. She pushed him away, and again he slapped her. “Every time I pushed him away again, I got another slap in the face,” McMaster said. “People were starting to look because Fourth Ave is a pretty busy street and there was a floodlight outside my building. I was basically yelling, ‘What the fuck! Please get off of me!’”

“Eventually people were starting to stop and look because I was screaming at him, trying to get him to stop,” she said. “And eventually he was like, ‘Haha, okay, maybe next time.’”

McMaster went back inside her apartment building, upset. She called her brother, Philip Kreyche, who told KUOW about their conversation that night.

“She was a little bit in shock from the whole experience,” Kreyche said. “She said, ‘That was weird, wasn't it? I’m not crazy am I?’ I said, ‘No, you're not crazy. That's not okay, what he did.’”

Still, McMaster was torn about whether to bring attention to Meinert’s alleged behavior. “She was afraid if she called him out and took him to task for it, she would lose out on job opportunities,” Kreyche said.

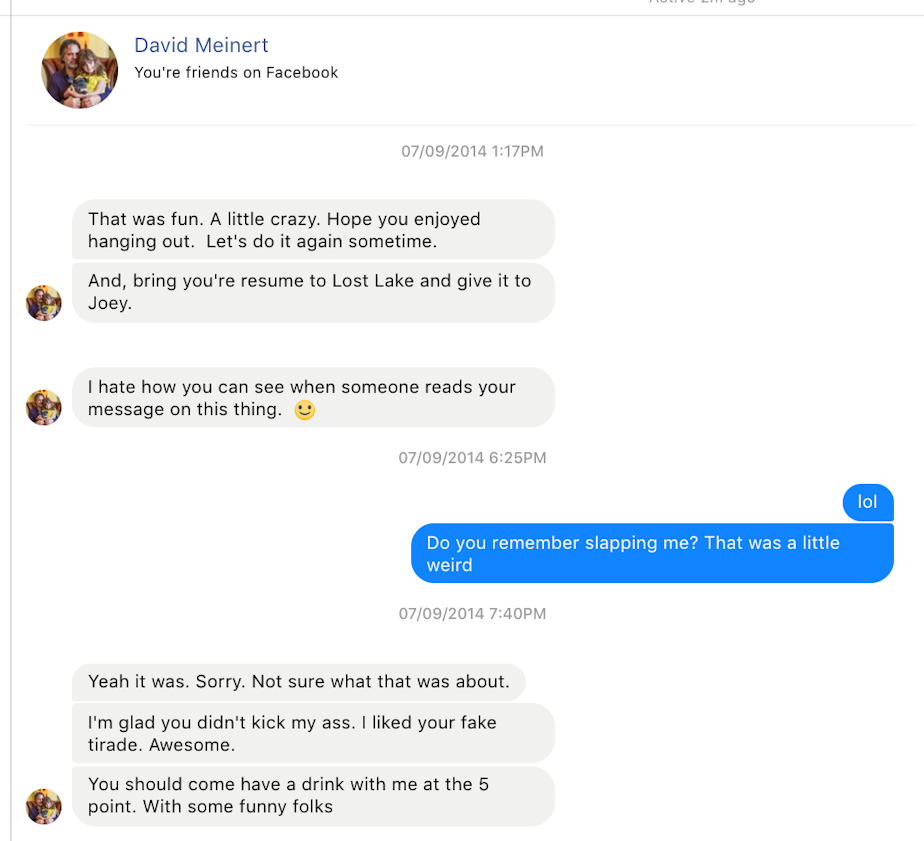

The next day, Meinert messaged McMaster on Facebook. “That was fun,” he wrote. “A little crazy. Hope you enjoyed hanging out. Let’s do it again sometime.” He instructed McMaster to drop off her resume with Joey Burgess at Lost Lake.

At first, McMaster didn’t respond. But when the chat showed she had read his message, Meinert sent another: “I hate how you can see when someone reads your message on this thing.”

McMaster still wanted the bartending job. She didn’t want to be “aggressive” and lose out on the opportunity, she said. “lol,” she wrote. “Do you remember slapping me? That was a little weird.”

“Yeah it was,” Meinert said. “Sorry. Not sure what that was about.”

He continued: “I’m glad you didn’t kick my ass. I liked your fake tirade. Awesome.”

McMaster said she was terrified, but still dropped off her resume at Lost Lake. She never heard back.

“At the time I didn't really think that much of it,” McMaster said later. “I was depressed. I didn't have a lot of respect for myself and understand what was and wasn't my fault.”

‘I hope it’ll help someone else’

After the first five accusers came forward, Meinert denied the specific allegations of rape and sexual assault. Prosecutors had declined to charge an accusation from 2007, and Meinert said he had no idea why two other women would make rape and sexual assault allegations years later. He had never had sexual contact with the newest rape accuser, and he had sex with the sexual assault accuser consensually, he said.

Two other lower-level allegations from other women could have been plausible, Meinert added, though he didn’t recall the specifics. He had been “handsy” in the past, he told KUOW, but he was learning from his mistakes. He spoke in sympathetic terms about the #MeToo movement and insisted he was not a rapist.

Meinert did not respond to these six new allegations. But several of the women who responded to the first piece say those allegations gave them the confidence to share their stories publicly.

Eryn Young, the musician who said she was assaulted by Meinert at his club in 2004, said she hopes this encourages others. A mutual friend, she said, knew one of the first accusers and told her coming forward to KUOW had been like “going through hell.”

“I feel like I’m not going through hell here,” Young said. “I dealt with this a long time ago, but I feel like I need to say very matter-of-factly what happened to me. And I hope it'll help someone else.”

“I'm not ashamed,” Young said. “This is what happened.”

Correction, 10:55 a.m., 8/9/18: The original version of this piece misstated the location of On the Boards. Due to an editing error, the piece also misstated the location of the Mirabeau Room.

Reporter Sydney Brownstone can be reached at 206.353.3729 or sydney@kuow.org.