She called 911 and said she was suicidal. Then she was charged with a crime

“911, what is your emergency?”

“My name is June,” said the woman on the line, her voice matter-of-fact. “I’m suicidal. I would like some officers to come out and talk to me, so that way I can feel safe.”

June was 35, lived in Seattle, and had the dubious distinction of being one of the city's top five most frequent 911 callers.

Last year, she called 911 more than 60 times.

Listen to the call (captioned):

Sponsored

And then, after June called five times on St. Patrick’s Day, something unexpected happened: A Seattle prosecutor charged June with false reporting, a misdemeanor crime, to deter her from calling 911 so often.

June’s case revealed a snag in the system: What to do with frequent callers? In 2014, the Seattle Fire Department found 500 frequent callers — people who called 911 more than 20 times in the year.

Jon Ehrenfeld of Seattle Fire said these callers are often filling a gap in health care or social services. Many are elderly.

“They’re aging in place, calling 911 because it’s their de facto health care,” he said.

Ehrenfeld is on a team that reaches out to these frequent callers. The team includes a social worker who connects people with family members, medical help and, for people like June, mental health services.

S

t. Patrick’s Day was the final straw.

June’s first call to 911 was after midnight. Her voice was even, like she knew the drill.

As the operator asked about June’s plans to harm herself, and whether she had weapons, June grew impatient.

“Can you just have the police come out?” June said.

“I’ve got a call in for you, okay?” the operator replied.

The operator asked about the night before, when officers came to her apartment.

“Well, it’s another day,” June said, “and I’m feeling suicidal again, so that’s what’s going on.”

The call lasted about 10 minutes.

Sponsored

Twelve hours later, June called again. She asked for the Mobile Crisis Team. She debated the finer points of emergency response policy with the operator.

Then she delivered the line that changed the tone of the call: “I need some officers to come out to my house because I’m suicidal.”

Three-second pause.

“What’s your address?”

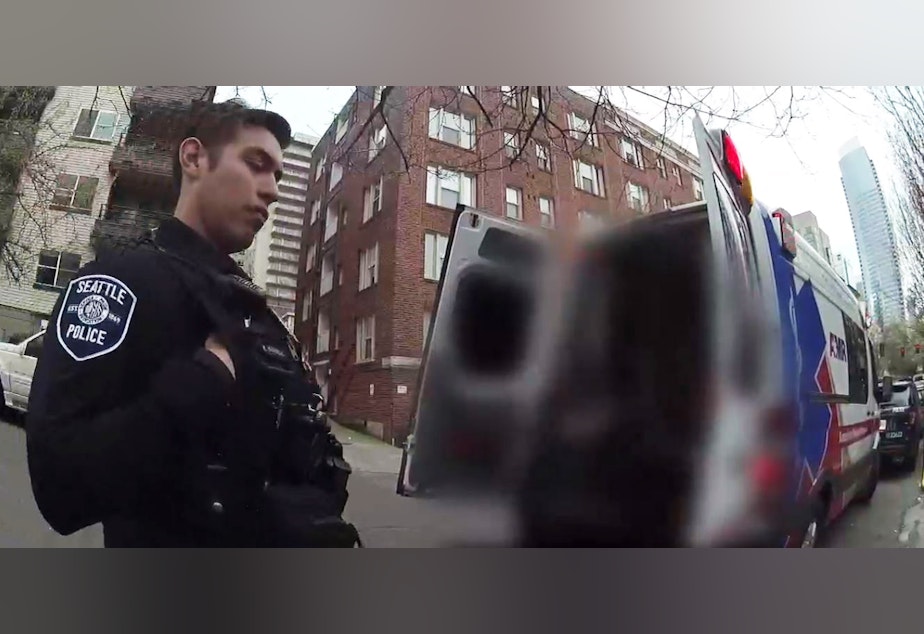

An officer arrived, and then an AMR ambulance. As June went upstairs to grab her things — wishing passers-by a Happy St. Patrick’s Day as she did — an ambulance crew member approached the officer.

Watch the body cam footage:

“I’m sure you guys are familiar with her,” the officer said.

“Yup, know her well,” the ambulance worker said, and then took June to Swedish Medical Center.

Three hours later, June was home again, dialing 911.

This time the Mobile Crisis Team came, but June “declined to use their services,” according to a police report.

When June called 911 again, at 5 p.m., the operator sounded impatient.

“Looks like we already have a call in about this,” he said. “Did you call us, or someone else in your family?”

There was a slight pause before June answered.

“Uh, maybe someone else in my family probably did,” she said.

“I show that someone named June called from this number and already requested an ambulance,” the operator said.

“That’s me,” June said. She felt suicidal again, she said. “I just call for help because I don’t want suicidal thoughts to lead to something.”

When the operator called the ambulance service, the dispatcher there was incredulous.

“We actually went there – not kidding you – eight times yesterday,” they said.

This time, Sergeant Joshua Ziemer arrived at June's apartment with a message.

Listen to the sergeant's conversation with June:

T

en days after St. Patrick’s Day, Assistant City Attorney Andrea Chin charged June with false reporting. The charge read: “The crime of false reporting by making a verbal statement relating to a crime, catastrophe, or emergency to a Seattle Police officer or a Seattle Police Department 911 emergency operator…”

Chin said there was disagreement in her office about pursuing the charge against her. “The behavior continued and still continues,” she said. “We are trying to curb that behavior.”

June’s attorney, Sarah Wenzel of the Northwest Defenders Association, said the charge criminalizes mental illness. Sending June to court would not help her, Wenzel said.

“I think how we should deal with mental health is through giving people the mental health resources that they need,” Wenzel said.

The court didn’t buy the charges — lack of probable cause — and June’s case was dismissed.

The charge did not act as a deterrent. At last check, June’s calls to 911 have continued.