Mayor Durkan's new anti-displacement strategy has precedent — in New York City

As Seattle grows, politicians are considering new ways to keep longtime residents where they are.

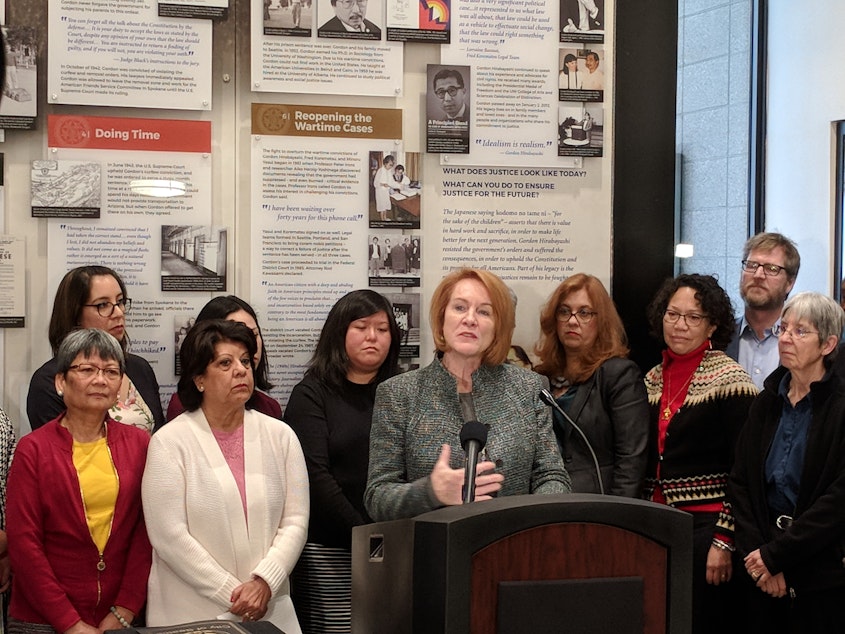

This week, Mayor Jenny Durkan signed an executive order with a number of anti-displacement strategies.

But one strategy in the order stands out. Durkan has directed the city’s Office of Housing to establish something called a community preference policy.

This policy would give developers who get city funding the ability to set aside a portion of units in new affordable housing buildings for residents in that community.

"We want to make sure that those people who would be the first to be pushed out by redevelopment and growth can be first on the list for the housing that the city is investing in," Durkan said.

She said the city will work with lawyers to make sure the policy is legally sound and doesn’t run afoul of fair housing laws.

Housing officials say this policy would be implemented on a case-by-case basis — that it would not be a city-wide mandate, but meant to encourage non-profit developers to propose this as part of their developments. They also said it would be focused in neighborhoods where residents are at greatest risk of displacement.

Officials say this is something happening informally already, and something city-funded developers have expressed interest in formalizing. Similar policies are in place in other cities, including New York City and San Francisco.

But those policies haven’t arrived without pushback.

New York has had community preference policies in place since the 1980s. They apply to projects city-wide and set aside 50 percent of units for neighborhood residents during initial leasing, according to a Seattle Office of Housing memo. They’ve also been challenged in court.

A lawsuit brought by three African American women in New York claims the policies perpetuate segregation and violate the fair housing act. According to court documents, the plaintiffs say community preference has a disparate impact on people of color who are seeking affordable housing in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Officials from Seattle’s Office of Housing say they’re aware of criticism of these policies, but they believe they can be implemented in such a way that furthers fair housing and inclusion, especially since the idea here is to allow this on a case-by-case basis.

They say communities in areas that have seen longtime residents displaced are calling for more tools.

Durkan said the city will fund 3,600 new, low-income, affordable units by 2022. The Office of Housing will be working up guidelines for the new community preference policies in the coming months.

City Councilmember Lisa Herbold said the mayor’s plan is useful for non-profit developers.

“Nevertheless, we also desperately need a tool to address the displacement that occurs when for-profit developers build," Herbold said in a statement. "Displacement is a challenging issue and we need many tools to address it."

Herbold has proposed her own legislation that would require developers who tear down affordable apartments in certain neighborhoods to mitigate the loss of that housing.

They could do that through paying into the city’s fund for affordable housing, or by making an equal number of apartments in their new development affordable to people making 80 percent of the area median income – roughly $56,000 for a single adult.