Seattle Schools knew these teachers abused kids — and let them keep teaching

UPDATE: Seattle Public Schools has removed teacher James Johnson from the classroom. Read about that here.

On a rainy morning two years ago, James Johnson, a Seattle teacher, punched an eighth grader in the jaw.

They were in math class at Meany Middle School on Capitol Hill, with 32 students in the room. The boy, who is black, had called Johnson, who is also black, the N-word, according to students who were there.

Johnson called the boy the N-word back, some students said.

LISTEN: Teacher James Johnson admits to punching a child in a face.

He got in the boy’s face, taunting him, and challenging him to respond. Students said the boy pushed his teacher in the chest to get away.

A district investigation found that Johnson then grabbed the boy by the shirt, punched him, and shoved him out of the classroom.

Hallway security camera footage shows the boy being violently pushed into the hallway, legs flailing. Seconds later, Johnson hurls the boy’s backpack into the hallway.

Keenan McAuliffe, a student in the class, said a hush fell over the room.

“Everyone was kind of just shocked,” Keenan said. “I was like – what the heck? I’ve never seen anything like this.”

Johnson was not fired — even though a Seattle Public Schools investigation found that he had punched his student in the face.

Instead, he received a five-day, unpaid suspension and conflict management training. He currently teaches math at Washington Middle School.

Sponsored

A KUOW investigation found that Seattle Public Schools often allows teachers who harm students to stay in the classroom. Some are allowed to keep teaching even after multiple offenses.

The district has also, on at least one occasion, removed evidence of misconduct from a teacher’s personnel file after forcing them out of the district.

Through a public records request, KUOW obtained records for 10 cases in which teachers were disciplined for verbal abuse, physical abuse or sexual harassment against children in Seattle Public Schools from 2012 to 2018.

Education attorneys told KUOW these 10 cases could potentially have resulted in termination. In only one case was a teacher actually forced out of the district. The cases include:

A kindergarten teacher who was found to have pulled a student’s arm until she fell down, then told the girl “that is what you get when you don’t follow directions,” and denigrated another kindergartner in front of staff and students. The teacher received a written reprimand.

Sponsored

A special education teacher found to have slapped a young child on the face hard enough to leave a mark, then lied about it. That teacher got a 10-day suspension.

An elementary school teacher with a history of yanking children’s hair was found to have pulled a slouching child by his ears “from a reclined to an upright position in his seat,” leaving the child quietly sobbing for the rest of class. The teacher received a written reprimand.

Shannon McMinimee, a former attorney for Seattle Public Schools, said she was “stunned and appalled” by the list of cases.

“I’m just not seeing a level of seriousness being considered with respect to behavior that’s physically and emotionally abusive to children,” said McMinimee, who is now in private practice.

After dozens of interviews with teachers, principals, district officials, school board members, union officials, state regulators, education attorneys, parents and students, KUOW identified seven major flaws in the system that allow problem educators to get hired and stay in the classroom.

1

Districts are reluctant to fire teachers.

It was not the first time James Johnson laid hands on a student. Personnel files from previous employers show a history of troubling behavior.

In 2004, Johnson was disciplined for pushing a student into lockers in the Clover Park School District, near Tacoma. The student’s chain necklace broke during the conflict.

Johnson was also counseled four years later, in the Kent School District, for anger and profanity in the classroom.

[Read about a Kent teacher who tweeted racist, bigoted messages. She's still teaching in the district.]

And students and staff had complained about his behavior in at least three Seattle schools, including allegations of sexual harassment and inappropriate behavior toward teen girls.

After Johnson punched the boy at Meany Middle School, the district’s human resources department recommended that he be fired, said Clover Codd, who said she has led the department for three-and-a-half years.

But after a hearing with then-Superintendent Larry Nyland, in which Meany Principal Chanda Oatis spoke on Johnson’s behalf, Nyland instead gave Johnson a five-day suspension. (Footnote 1)

“You are recognized as a leader and are well-liked by both staff and students alike,” Nyland said in a discipline letter to Johnson.

Johnson turned down interview requests and referred KUOW to his lawyers, who did not respond. He has claimed in writing that he punched the student instinctively, in self-defense, after the student pushed him.

Student Elinor Earle was shocked to learn that her teacher could return after punching her classmate.

“How does someone get away with assaulting a minor?” Elinor said recently. “It doesn't make a lot of sense to me.”

Elinor said she and her classmates wanted to skip Johnson’s class on the day he returned, “because we watched [the assault] happen, and he knew that we saw it happen,” she said.

Two days after returning to school, Johnson was back on administrative leave: This time because of new allegations that he had sexually harassed and threatened students.

Those were the only two days Johnson worked over a 13-month span. He earned an estimated $134,000 during that time on paid leave from Seattle Public Schools.

Midway through that stretch, in June 2018, a district investigation found that Johnson had, indeed, sexually harassed students. He had touched girls on the shoulders and legs and made them uncomfortable, the district found.

He had baked a batch of brownies for one girl, an investigator wrote, and called female students “sweetheart,” “honey,” and “baby.” A student who had gotten help from him at lunchtime said she stopped going “because he ‘creeped’ her out,” the investigator reported.

The district also initially found that Johnson had told students, “If you mess with me, you will have to have my foot removed from your ass.”

Johnson has denied these claims.

Several months later, the district sent Johnson notice for the second time that year that it had probable cause to fire him – this time, for sexual harassment and intimidation.

He still did not lose his job. He was reassigned instead to The Center School as an “intervention specialist,” working one-on-one with struggling students.

Personnel files show a Seattle Schools human resources official recommended against firing Johnson after the district re-interviewed key witnesses and found the evidence regarding the intimidation allegations was inconsistent. It is unclear why the sexual harassment findings did not result in discipline.

During Johnson’s tenure with the district, three different superintendents would give him a reprieve from termination.

The district declined multiple requests for interviews with Superintendent Denise Juneau. Former superintendent Larry Nyland did not respond to interview requests. Former superintendent Maria Goodloe-Johnson died in 2012.

2

Teachers get hired despite inadequate reference checks.

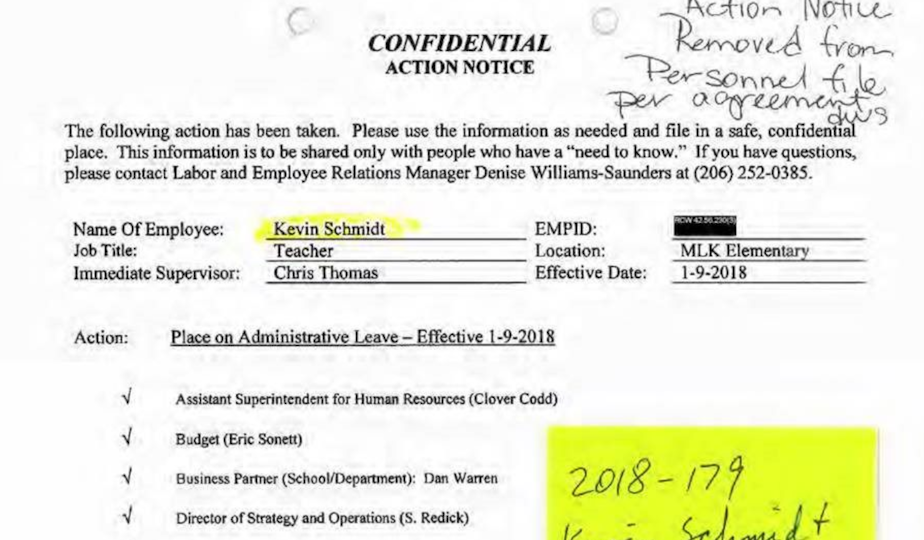

Kevin Schmidt was one year into his time as an elementary school teacher in Seattle Public Schools when he was placed on administrative leave.

Schmidt was under investigation for physically and verbally abusing children as the P.E. teacher at John Hay Elementary school on Queen Anne.

The 2016 district investigation found that Schmidt “slapped, swatted or hit” a student’s hand down when she raised it to ask a question. In another incident, Schmidt, who is white, reportedly implied to a student that African-American children all look alike.

The investigation found that on numerous occasions Schmidt had shamed children, made students cry, and yelled at both children and adults.

Schmidt spoke to KUOW at length about the allegations. He denied shaming students, and saying that African-American children all look alike.

He said he does not remember yelling at staff or students, or making children cry, but said his memory is imperfect. Schmidt said he has a traumatic brain injury from a 2015 car accident that he said caused “crazy emotional outbursts.”

Schmidt had started an application for medical leave because of his erratic behavior just days before the John Hay principal put him on administrative leave.

“It worked out better in one sense, because I got paid on admin leave, and you’re not paid on medical leave,” Schmidt said. But he said it was unfair to discipline him for behavior related to a medical issue.

After a district investigation found Schmidt had violated numerous district policies, he received a disciplinary warning.

He signed an agreement with the district that allowed him to keep teaching because of evidence that the 2015 car accident impacted his teaching ability.

“Through medical treatment he has significantly improved,” the settlement reads.

But personnel files from Schmidt’s previous school district show problems dating back to 2006.

Before Schmidt worked in Seattle, he had a long tenure in Steilacoom Historical School District, near Tacoma.

Records there show clashes between Schmidt and the principal of Chloe Clark Elementary School, where he worked for six years.

In 2006, Schmidt was disciplined for announcing his intention to take Fridays off for the rest of the school year. In 2013, he reportedly refused to remove chairs he'd stacked outside the principal's office, told the principal to write him up, and walked off.

Schmidt attributed those earlier incidents to working conditions at that school — and earlier head injuries that he said affected his behavior.

Schmidt said he has sustained between eight and 10 major concussions over his lifetime. “You’re talking to a guy with a broken brain,” Schmidt said.

No one in Seattle Public Schools spoke with that Steilacoom principal before hiring Schmidt one year later.

The district requires that hiring managers complete three reference checks before hiring a teacher. (Footnote 2)

“We should not be hiring any employee that we do not have reference checks for,” said Seattle Schools human resources chief Clover Codd.

Principals in several districts told KUOW that it can be hard to reach a teacher’s past supervisors or colleagues. “You’re lucky if anyone calls you back,” said Chris Cronas, a former principal in Seattle Public Schools and now an educational consultant.

“The biggest challenge is summertime,” Cronas said. “Nobody’s around to do a reference check. So you do the best you can with the information you’ve got.”

Cronas said a shortage of highly-qualified educators adds to the problem. “Competition for really strong people is so great. The pool’s too small,” Cronas said.

“There’s too many positions open. And we can’t fill positions fast enough,” he said.

3

Settlement agreements can hide abuse allegations.

After Kevin Schmidt was found to have verbally and physically abused students at John Hay Elementary, the settlement agreement he signed with Seattle Public Schools kept him on paid administrative leave for the rest of the school year, and moved him out of that school.

He was not in the displacement pool for long, however: Several months later, he was assigned to Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary School in the Rainier Valley as a kindergarten teacher.

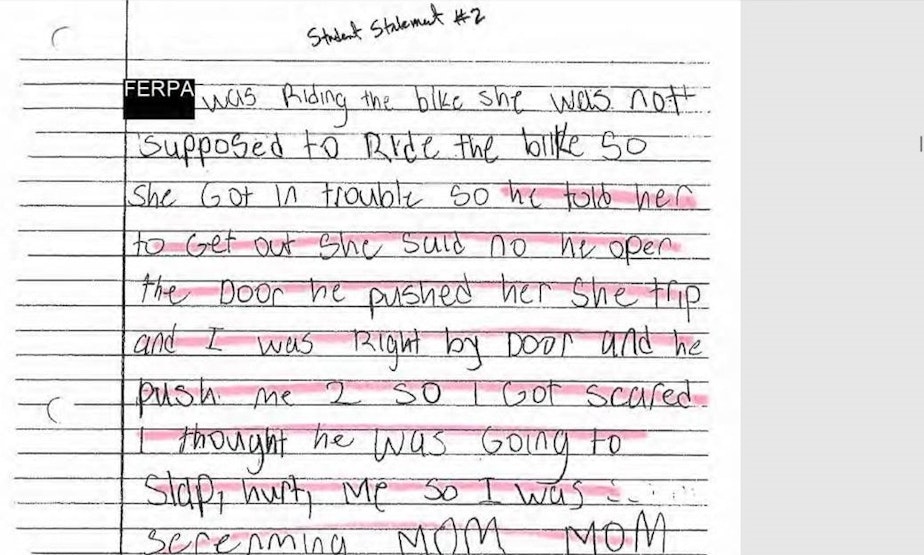

In 2018, Schmidt was on administrative leave again: this time, for allegedly pushing and yelling at two girls in his class after one of the children rode a bicycle the wrong way.

According to witness statements from the children involved, Schmidt had already yelled at and pushed one girl on the bicycle when he started yelling at a second girl to leave the gym.

In a written statement, a parent witness wrote that Schmidt “was yelling at the top of his lungs ‘GET OUT! GET OUT!’ while this child was screaming” for him to stop.

Schmidt shoved the girl out of the room, the parent wrote. “She falls to the floor in a corner near the door crying, ‘I want my mommy,’” she wrote. “I was brought to tears when I witnessed this.”

In Schmidt’s statement, he called Martin Luther King “an unsafe and hostile work environment.”

In disciplinary paperwork, Schmidt also accused the two fifth-grade girls of “gang-like behavior” in the incident.

After the district told Schmidt they planned to investigate the incident, he agreed to resign. He signed a second settlement agreement with Seattle Public Schools.

The district agreed to pay Schmidt for the rest of the school year – five months — and to remove the latest incident from his personnel file.

That meant future districts could not easily learn that he was accused of mistreating children for the second time in roughly two years.

State law prohibits districts from entering into agreements that have “the effect of suppressing information about verbal or physical abuse or sexual misconduct by a present or former employee,” the law reads, if the misconduct has been substantiated.

Seattle never substantiated the newest abuse allegations against Schmidt, because the district stopped investigating when he agreed to resign.

“It sounds like the district may have followed the letter, but not the spirit of the law,” said education attorney Jinju Park. “Putting its head in the sand does not relieve it of its legal duty.”

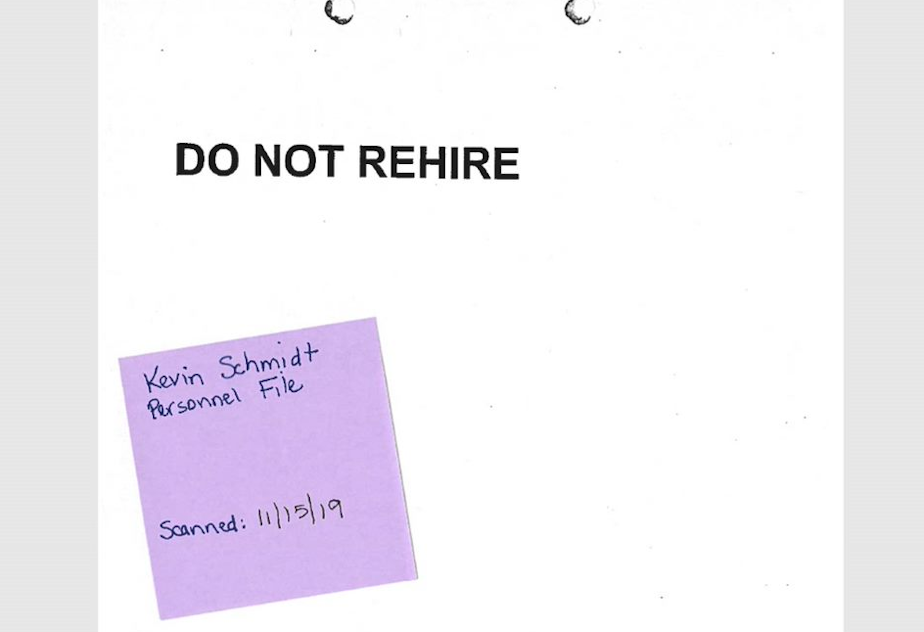

Under Schmidt’s deal with Seattle Public Schools, he was no longer allowed to work in the district.

The top page of his personnel file now reads in giant type: “DO NOT REHIRE.”

Despite that, just two months later, in May 2018, Schmidt was hired as a substitute teacher in the Tacoma School District.

He was now collecting paychecks from two school districts: Tacoma, where he was actively teaching, and Seattle, where the district had let him stay on paid administrative leave through August.

That fall, Schmidt took a full-time teaching job in Tacoma.

Three months into the school year, Schmidt resigned in lieu of termination in that district, too, after he was disciplined for emailing parents at Stewart Middle School about “concerns I have, and I believe you have about the functioning of our classroom over the 45 days since my arrival.”

Schmidt told parents that he did not have the training or experience to teach 7th grade math, and that the district had failed to support him.

Again, Schmidt signed a settlement agreement guaranteeing him full pay and benefits for the rest of the school year, at an estimated cost of $62,000.

It was his third settlement agreement in four years.

Schmidt's three rounds of administrative leave and two contract buy-outs cost Seattle and Tacoma School Districts an estimated $268,000 in salary and benefits alone.

4

Superintendents fail to notify the state of serious misconduct.

State law requires that superintendents report evidence of serious misconduct to the state Office of Professional Practices for possible suspension or revocation of an educator’s credentials.

Superintendents often fail to comply with the law.

That means abusive teachers can keep teaching in Washington state and elsewhere.

Even after Seattle Public Schools disciplined Kevin Schmidt, the district never notified the Office of Professional Practices. The state agency learned of Schmidt’s disciplinary history from KUOW.

When the state then subpoenaed Schmidt’s personnel records from Seattle, the district “said they didn’t think they had to send it to the state, because he’d resigned,” said Catherine Slagle, the director of the Office of Professional Practices.

In fact, state law requires that superintendents notify the state within 10 days after an educator is forced to resign or fired for misconduct.

Clover Codd with Seattle Schools said district officials previously interpreted the law to mean that they must report misconduct only if an investigation been completed.

“We’ve changed our process” since talking with the state about the Schmidt case, Codd said.

From now on, “even if an employee resigns and we haven’t finished the investigation, if we have some evidence and witness statements that a potential act of professional misconduct occurred, we’re going to report that,” she said.

Slagle said she sometimes learns of problem educators not from districts, as the law requires, but from news reports.

“If I see something in the paper that is concerning to me, I pick up the phone and make a phone call to the district,” Slagle said.

Since 1993, there have only been three investigations into a superintendent not reporting misconduct.

No superintendent has ever been found at fault. (Footnote 3)

When the state started investigating Kevin Schmidt, he voluntarily surrendered his teaching license, “just so people stop bothering me,” he said.

Schmidt said he has stopped teaching and has opened a home decor business.

“You could make the argument I shouldn’t teach,” he said. “Should I have gotten out earlier? Absolutely. But when you’re having medical issues, you don’t make the best decisions.”

5

Misconduct investigations fail to examine historical allegations.

Long before a 2018 district investigation found James Johnson had sexually harassed students at Meany Middle School, educators at various Seattle public schools had reported similar incidents.

District officials, including in the legal office, had been informed about at least some of those allegations over the years.

Despite this disturbing track record, the district did not appear to take his history into account when investigating the 2018 sexual harassment allegations.

According to district records, investigators did not interview any of Johnson’s past supervisors or colleagues regarding the new reports of abuse.

In 2012, at McClure Middle School on Queen Anne, staff called 911 after the school principal ignored their complaints that Johnson appeared to be grooming students for inappropriate relationships, said a former teacher at that school who asked to remain anonymous out of fear of reprisal by the district.

“At one point, he was walking down the hall with his arms around the waists of two 13-year-old girls,” the teacher said.

Teachers complained to the principal, he said, but to no avail. “It was just sick. We felt like there wasn’t any action being taken.”

In 2010, when Johnson taught at Nova, an alternative high school, e-mail records show that Principal Mark Perry reported students’ allegations of sexual harassment to district headquarters.

“Female students … came to me, often in tears, and reported that when they were doing work in class, he would come up to them from the back, put his arm around them, and breathe and talk softly into their ear and say things like how good they looked that day,” Perry said in an email to a district staffer.

Perry said when he reported the allegations to the district, he never heard back.

According to Perry’s email, a teachers union representative told Perry he had not reported the allegations in the mandatory time window.

Johnson was still new in the district, and on a provisional contract. Perry did not renew the contract at the end of the year.

Johnson appealed to then-Superintendent Maria Goodloe-Johnson.

“After meeting with you on Friday, May 28, 2010, I have reconsidered the decision to non-renew your employment contract with Seattle School District,” Goodloe-Johnson wrote in a letter to Johnson.

“Since your current position is still available, you will be returned to a teaching assignment at Nova High School for the upcoming year,” she wrote.

She gave no further information about the reason for her decision in the letter.

The following year, Perry wrote to district officials again about Johnson’s behavior toward students, “which I have documented for two years and made as clear as I can.”

Perry said two years of student reports were unsettling: Students told him, he wrote, that Johnson gave special attention to “cute” girls, and belittled and mocked girls “with self-confidence issues.”

“I believe Mr. Johnson is a danger to our students,” Perry told district officials in the email.

“I don’t say this without knowing that these are serious accusations,” he continued. “I don’t want to be the one later who is asked after … a student is seriously damaged, and/or a lawsuit is filed and someone asks why we didn’t know and/or why we didn’t do anything.”

6

The state says a teacher is dangerous. The district still lets them teach.

Although Seattle Public Schools has not fired Johnson for any of its misconduct findings, ranging from sexual harassment to assaulting a student, the punch did land him in Seattle Municipal Court.

Johnson received a two-year deferred prosecution for assault, including 32 hours of community service, a no-contact order with the student victim, and fines.

His next hearing is scheduled in June.

Earlier this year, the state Office of Professional Practices issued a proposed order for a six-month suspension of Johnson’s teaching certificate and for him to undergo a psychological evaluation “which validates his ability to have unsupervised access to students in a school environment.”

The agency later extended the proposed order to an eight-month suspension, citing, among other things, “clear and convincing evidence the Educator has a behavioral problem which endangers the educational welfare or personal safety of students, teachers, or other colleagues.”

Investigators said they had learned that Johnson lied to them about having no previous discipline history in other districts, when he had been sanctioned for pushing a student into lockers in Clover Park School District.

The state found that Johnson had also failed to disclose that discipline on two applications for his teaching certificate, as well as on a job application to teach in Seattle Public Schools.

Failure to disclose past discipline on an application is, itself, an act of misconduct that can result in termination at the district level, and action against an educator’s certificate at the state level.

Seattle Schools human resources chief Clover Codd said she was not aware of the state’s findings regarding Johnson’s past discipline and his failure to report it to multiple agencies, including Seattle Schools.

Johnson is appealing the license suspension, and remains in the classroom in Seattle.

When teachers are facing license suspensions, they have usually already been forced out of their jobs as a result of the misconduct at issue, said Catherine Slagle, head of the Office of Professional Practices.

Otherwise, teachers are usually placed on administrative leave pending the outcome of the state discipline case, Slagle said.

Asked why Johnson is still teaching, Codd did not reply.

An attorney from the Washington Education Association, the state teachers’ union, is representing Johnson in his fight to retain his license. The next hearing in the case is scheduled for May.

WEA spokesman Rich Wood said the union routinely represents any educator facing the loss of credentials, “because it’s an important decision that’s being made there, whether they will keep their license and be able to still teach,” Wood said.

“They have the right to due process and to make sure that their side is being heard,” he said.

7

The district has a history of lenient discipline.

“Organizational culture is shaped by what you celebrate, what you tolerate, and what you absolutely will not allow,” said Rick Burke, who recently stepped down from the Seattle School Board.

“We’re tolerating this kind of behavior in our schools, and it creates that sort of culture.”

Attorney Shannon McMinimee said that while unions represent teachers accused of misconduct, it’s ultimately up to districts whether to fire an abusive teacher – and the state whether to let them keep teaching in public schools in Washington.

McMinimee said she sees a pattern of lenience in the 10 disciplinary cases of Seattle teachers abusing students that KUOW reviewed.

That’s important, she said, because discipline decisions are typically based on precedent: When unions and districts discuss how to discipline a specific teacher, they review how similar incidents were handled in the past.

“I think that the district has created a circumstance whereby the union has the ability to say, ‘Why on Earth are you proposing to fire this teacher?” McMinimee said. “Because you’ve let seven other teachers who’ve done the exact same thing get off with a written reprimand, or a one-day suspension.”

She said she’s seen districts reset their staff discipline standards, including during her time as general counsel in Tacoma Public Schools.

Doing so requires that the superintendent and district leaders sit down with union officials to agree on what are fireable offenses, and what is negotiable.

“I would hope that everybody would want to discuss a shared set of values, and what types of conduct are never going to be acceptable,” McMinimee said.

“I absolutely think that would be extremely helpful,” Codd said. She said she has spoken with the Seattle Education Association, the district’s teachers union, and other labor organizations about taking that step.

Seattle Education Association officials declined to comment for this story.

The district has undertaken what it terms an “HR transformation” in recent months, after commissioning an outside audit of the district’s Labor and Employee Relations department.

While many allegations of misconduct were previously investigated by school leaders, Codd said that she has overseen a streamlining of processes, and centralized oversight of more severe employee misconduct allegations, “which I think have already helped us put much more scrutiny on our investigation processes.”

//

When Kevin Schmidt learned that the state was investigating his discipline history in Seattle Public Schools, and considering taking action against his teaching license, he said he was surprised that Seattle had never reported him before.

Schmidt assumed he was under scrutiny now because a new superintendent, Denise Juneau, had taken over and decided to report him.

When told that the state review was, in fact, spurred by KUOW’s investigation, Schmidt chuckled.

“I mean, that highlights how the system is broken,” he said.

Clarification: We have added detail to clarify the district finding that Johnson told students, “If you mess with me, you will have to have my foot removed from your ass” as an initial finding, that was later found to be inconsistent after the district re-interviewed key witnesses. We also updated the story to describe the state's orders to suspend Johnson's license as 'proposed' orders.

Do you know about verbal, physical or sexual abuse of students in public or private schools? We’d like to hear your story. Contact Ann Dornfeld at adornfeld@kuow.org or (206) 221-7082.

This story was reported and written by Ann Dornfeld, and edited by Liz Jones and Isolde Raftery.