Seattle program addresses key gap in the opioid crisis: post-overdose support

Seattle Fire Department paramedics and EMTs have responded to more than 4,000 overdose calls so far this year, already surpassing the total number of calls for 2022. Many involve the powerful synthetic opioid, fentanyl.

Dr. Callan Fockele sees the impact of this crisis in Seattle on a regular basis.

Callan is an emergency and addiction medicine physician at Harborview Medical Center.

Several years ago, working in the emergency room, she recalls seeing a young man who came in after a heroin overdose.

She discharged him with the available resources she had at that point, a take-home kit with naloxone — the overdose reversal drug — and a phone number.

A few hours later, Callan said she got a call from paramedics. The same patient had died. Next to him they’d found drug paraphernalia and hospital paperwork.

Sponsored

People who have experienced an overdose face a dramatically increased risk of death in the following year, comparable to the risk of death following a severe heart attack.

“Think about all we do for patients who suffered a heart attack,” Callan said at a media briefing Tuesday. “They’re hospitalized, started on medications, and discharged with close outpatient follow-up.”

“What did I do for my patient?" Callan said. "I gave him a naloxone kit and a turkey sandwich.”

In the past few years, the opioid crisis has only gotten worse as fentanyl has become increasingly common.

With medications available that can help curb opioid use disorder, Callan said the system overall needs to do better for people who experience an overdose.

Sponsored

As officials in Seattle continue to try to address the current crisis, one new approach they’re trying involves engaging people directly after they’ve been stabilized following an overdose.

The Health 99 overdose response unit was formed in July. It’s run out of the fire department and includes a firefighter/EMT and a caseworker.

The goal of the unit is to engage people with services and support directly after an overdose.

The team does not do the initial emergency medical response but takes over once the individual has been stabilized.

They do not respond to every call, but respond to an average of three to five calls per shift, according to fire department officials.

Sponsored

To date, the team has engaged with 52 individuals, some on multiple occasions.

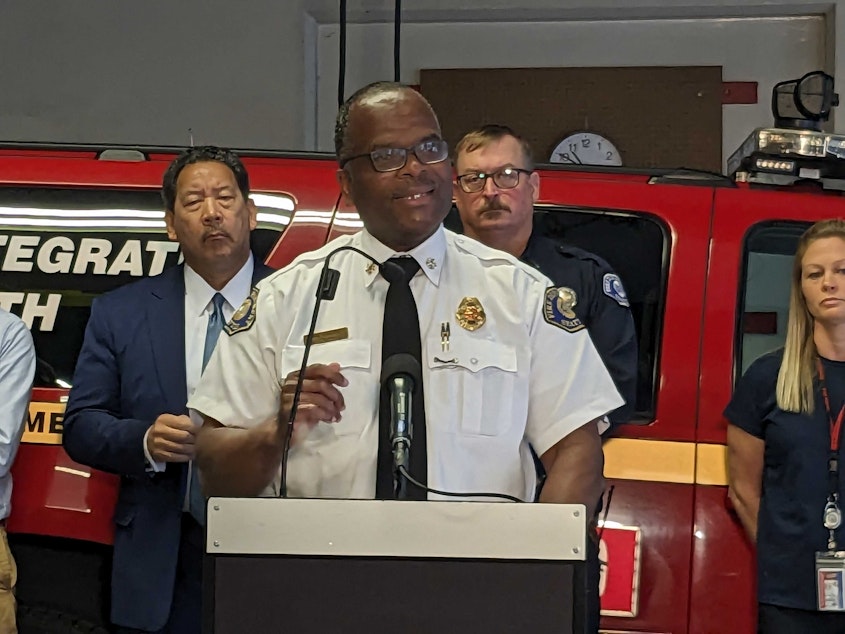

According to Seattle Fire Chief Harold Scoggins, 77% of people served by Health 99 are male, and most are experiencing homelessness and have a history of mental health disorders.

“With the success we have had thus far in the pilot, there are so many difficulties and barriers to this work,” Scoggins said at the media briefing.

Barriers include difficulty finding clients who are experiencing homelessness in order to follow up with them, difficulty at times finding somewhere for someone to go when they accept services, and a lack of ability or interest in accepting services among many clients who are engaged.

For those people who are interested in treatment, the team aims to take them directly to a clinic where they can get medication to help curb opioid use.

Sponsored

When a person is not ready to be connected with outpatient substance use services, or other services, the team will still engage the person in conversations and provide harm reduction services like overdose reversal drugs.

“We acknowledge that we’re not dealing with a single crisis, but rather a set of overlapping needs including homelessness, mental health care, poly-substance use, lack of housing and shelter options and more,” said Jon Ehrenfeld, manager for Seattle Fire’s Mobile Integrated Health Program, which encompasses the pilot overdose response team.

Members of the team say one thing they need is more services to be able to connect people with, including housing, mental health, and substance use disorder services.

In July, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell announced more than $20 million for treatment programs and facilities.

The City Council is also expected to hear legislation next week that would allocate funds for the creation of an overdose recovery center, a designated location where people could be taken after an overdose.

Sponsored

Those initiatives will likely take time to come to fruition.

For now, the Health 99 pilot is expected to run for three to six months.

Officials did not give specific metrics Tuesday that will be used to evaluate the success of the program and determine whether it will be continued in the future.

From his perspective, Scoggins said getting even one person into treatment and helping to change their life constitutes success.

Additionally, he said being able to engage people in conversation, provide them with education and harm reduction supplies, and build trust also contributes to success.

“We may not get them into services the first time, but maybe it’s the second time,” he said.