Seattle Now: Go deep — piloting Puget Sound

Safely navigating narrow Puget Sound passages is tricky business, especially for cargo boats. Port pilots and scientists make these journeys possible.

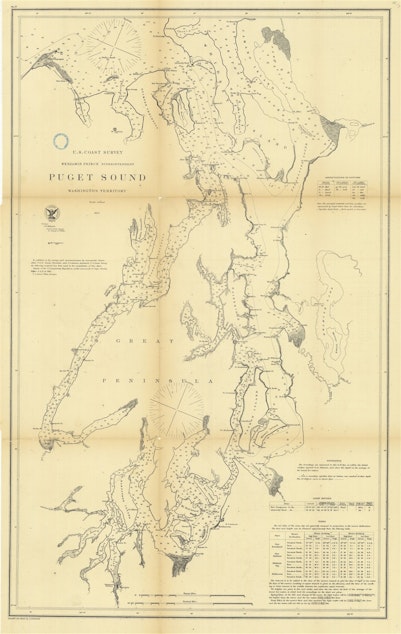

Seattleites take deep pride in all of the water cutting through and surrounding our city. The straits and passages that define this region cover over a thousand square miles. To move through these waters, ships rely on nautical charts to reach their destination.

In this episode of Seattle Now, Jennie Cecil Moore talks with port pilot and former tugboat captain Brad Lowe, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist Crescent Moegling, and oceanographer William Sweet to explore the challenges and adventures in navigating the winding waters of Puget Sound.

Sponsored

The transcript below has been edited for clarity.

BRAD LOWE: This is very old, seafaring tradition. It’s not unique to our era or to the Puget Sound, it’s universal, everywhere in the world. All ports have pilots.

Sponsored

[sound of trucks and harbor]

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Brad Lowe has been a pilot with Puget Sound Pilots for six years, and a tugboat captain before that. The group of mariners has specialized training and knowledge of local waters.

Past a line of idling trucks on Alaskan Way in Seattle, a hidden driveway leads to a small stretch of rocky beach. Jack Perry Memorial Park looks across the Duwamish Waterway where trucks and forklifts shuttle containers onto a massive cargo ship.

BRAD LOWE: So when you see a ship out on Puget Sound somewhere, there is a person, a local person, who is licensed by both the state of Washington and by the United States Coast Guard, to navigate, specifically to navigate vessels in and out of these waters.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Lowe says captains are not expected to know all of the waters and harbors of ports around the world. So ships hire local pilots to navigate the waterways that they’re not familiar with.

Sponsored

1 min

Brad Lowe, former tug boat captain, on annoying the local wildlife while working on the Puget Sound.

1 min

Brad Lowe, former tug boat captain, on annoying the local wildlife while working on the Puget Sound.

BRAD LOWE: Piloting is as old as seafaring. Ancient Egypt had pilots and ancient Greece had pilots. Pilots are mentioned in the Old Testament of the Bible. Again, for the same reasons because somebody sailing a ship from, say, Greece to Alexandria 2,000 years ago wasn’t expected to know the waters around Alexandria.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: When Lowe is on duty, he’s on call 24 hours a day and might get an assignment to navigate a ship from Anacortes to Port Angeles. His job starts with a meeting with the ship’s captain.

BRAD LOWE: The captain will tell me about the ship because I may not know anything at all about the ship, I will tell the captain about the voyage where we're going with the voyage plan is basically. Then I will "take the con," which is an old naval term, which means conduct the vessel, which means that I'll be in charge of navigating the vessel under the captain's supervision.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: For centuries, mariners used paper charts to navigate waterways, but in the last 20 years the charts have gone digital. Pilots have tablets called Portable Piloting Units.

Sponsored

BRAD LOWE: They’re electronic charts and we hooked them up, we have a GPS that we carry with us, and we have another device called a rate of turn indicator that we plug into the ship's AIS.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: The AIS is an Automatic Identification System. It’s a satellite system that tells the location of other vessels.

BRAD LOWE: And that brings up the electronic chart display and it displays where the vessel is on the charts and it displays all the other vessels that have AIS that are in the same region on the same chart that you’re on and so all of our stuff is is digital now. You know, we don't carry a bunch of paper charts on to a ship and many of the ships don't carry paper charts anymore either, many of them also have electronic chart systems.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: These charts are the work of NOAA – the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Scientists update these charts weekly to provide mariners with the latest information. Crescent Moegling is a NOAA scientist and the navigation manager for Washington, Hawaii, Oregon, and the Pacific Islands. She spent five years on the water early in her career.

Sponsored

CRESCENT MOEGLING: We spent quite a bit of time down in Key West, Florida, and we actually had a project out around the Dry Tortugas, it’s a really cool historic monument out there in the Gulf of Mexico. And the water there was just this cerulean blue and clear.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Moegling worked as a survey technician on a NOAA hydrographic survey vessel. They use sonar to collect data from the sea floor.

CRESCENT MOEGLING: Essentially, it's like mowing the lawn where you have a fan of information being collected beneath the the ship or the vessel. And more specifically, we use something called multibeam ECHO sounder where it's numerous beams of sound in the water way, so you get a very high resolution defined picture really of what the morphology is of the seafloor. In some parts of the country, we also use another technology called site scan sonar which is more of a visual of what the sea floor looks like, and this is also based on sound, but does not provide any depth information, it's more what physical objects are on the sea floor. And then of course we use GPS for positioning and then integrate information on tides to correct for the water levels as well.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: This mapping is critical for navigation and also serves to document changes to the sea floor and shoreline. William Sweet is an oceanographer with NOAA’s National Ocean Service. He studied the ocean, waves, and wind direction during his time at sea.

1 min

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist and navigation manager Crescent Moegling explains why Washington's deep waters are a benefit for mariners and the scientists who help them navigate the Puget Sound.

1 min

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist and navigation manager Crescent Moegling explains why Washington's deep waters are a benefit for mariners and the scientists who help them navigate the Puget Sound.

Sponsored

WILLIAM SWEET: We cross the Southern Ocean, had done Antarctica, and that's seven days of 20, 30 foot seas crashing over the bow sometimes and fantail and being told not to go out on deck because you might get swept over. So that was probably some of the roughest seas in the world, and some of the biggest things I've been in. And then you hit the ice and everything quiets down and flattens out and life is good.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Now Sweet focuses on studying changes in sea level and giving projections. The effects of climate change to navigation differ around the country.

WILLIAM SWEET: The southeast, the Atlantic, mid-Atlantic, the Gulf Coast areas where you have a very rapid rise and sea levels which oftentimes could be good for shipping you get more water under the keel, per se, but I think the challenge is systematically around the country certain areas sea levels rising, certain areas sea levels are about the same, certain areas sea levels are dropping. And to really make sure that that is being captured correctly on a cadence that’s sufficient to you know ensure safe navigation.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Looking at a series of charts over time can help harbor planners as they protect existing docks and develop new infrastructure.

WILLIAM SWEET: Where sea levels have been rising you definitely could have some interference with poor operations flooding, docks getting close to the water's edge. In the Pacific Northwest you have strong El Ninos tend to really bump up water levels for months, at a time, and those are the periods when "king tides" will occur, as it's known in those areas, and so that can have some impact on just overall port operations if the waters are too high.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Sweet says the northwest has not had many reports of problems due to high water levels compared to other parts of the country. That’s because Puget Sound is incredibly deep. Glaciers formed the region around 15,000 years ago and the Sound measures 930 feet at Point Jefferson, that’s just five miles northwest of Seattle.

WILLIAM SWEET: But you know sea levels are expected to continue to rise, so even in this part of the country where it has been relatively mild let's say an overall rate increases, moving forward that's not expected to be the case so it's going to either be how’s sea level the rising and falling and/or how's erosion changing you know any of the contours that might be affecting safe shipping and channels.

23 secs

At Jack Perry Memorial Park on Alaskan Way, you can look across the Duwamish Waterway and see a container crane loading containers on a cargo ship. Forklifts shuttle cargo back and forth and trucks line up to deliver more goods for transport.

23 secs

At Jack Perry Memorial Park on Alaskan Way, you can look across the Duwamish Waterway and see a container crane loading containers on a cargo ship. Forklifts shuttle cargo back and forth and trucks line up to deliver more goods for transport.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: And as sea level rises, NOAA scientist Crescent Moegling says the organization will be tracking the national shoreline.

CRESCENT MOEGLING: Not just for charting but for the whole nation and the world, and so when we do these shoreline surveys, we use technology from airplanes actually. using photogrammetry, where the airplane will take a series of very high resolution photos to get good detail on the shoreline. And so we're really going to need to be keeping up with those changes and reflecting those on our charts.

JENNIE CECIL MOORE: Back at Harbor Island, a ship gets ready for departure. Stacked high with containers, the vessel will make its way slowly out of Puget Sound. Part of what draws mariners to the profession is a shared admiration of the water. Again, pilot Brad Lowe.

BRAD LOWE: And it occurs to me that I do kind of take it for granted, I do think of it as you know, another day at the office. But you know once in a while you when you're out on the ship and it's a nice day, and it’s clear out with good visibility, you know, Kitsap Peninsula and the ferry docks — it's an amazing view.

This episode of Seattle Now was produced by Jennie Cecil Moore and hosted by Paige Browning. This web story was produced by Kristin Leong.

Want more Seattle Now? Follow us on Instagram @seattlenowpod, or send us a note at seattlenow@kuow.org.

What treasures do you think are at the bottom of Puget Sound? Send our producer a message at jmoore@kuow.org, or just head over to the side of this page and click the feedback button. We're listening.