Pregnant people weren’t included in the Covid vaccine studies. So how do they decide about the shot?

Dr. Emily Fay is a maternal-fetal physician at the University of Washington. She’s seen healthy young women who are pregnant get seriously ill with Covid-19.

“We've had women who were hospitalized with Covid pneumonia, intubated in the intensive care unit, women who have had to deliver preterm, sometimes even very preterm,” Fay said. “Some of my colleagues have even had patients who have died from Covid-related complications.”

As a doctor, Fay is eligible for the Covid vaccine. Normally, she would get it without hesitation, to protect her patients.

But there’s a wrinkle: Fay herself is pregnant, about six months along. And there’s very little data about the effects the vaccine might have during pregnancy.

That’s because almost no one who was pregnant was included in the clinical trials for the vaccine. At the start of the trials, if you were pregnant, you were cut.

Katie Schubert, president and CEO of the Society for Women’s Health Research, said historically, clinical trials only included men.

Even as drug companies started to include more women in research, they still excluded pregnant women, because of fears of what drugs might do to a developing fetus.

Sponsored

That was in part because of what had happened in the 1960s, when a drug called thalidomide was widely prescribed for morning sickness.

“It caused deformities in the baby — shortening or absence of limbs,” Schubert said. “It’s pretty horrifying when you sort of think about the use of medications that maybe you think are safe, but they turn out not to be.”

Schubert said drug manufacturers worry something similar could happen again, so they’ve generally eschewed including pregnant women when researching new drugs, treatments, or vaccines.

Over the years, drug companies have also expressed concern about liability, the complications of including pregnant people in research, and the potential damage to the rollout of a new drug or vaccine if someone in the clinical trials has a bad pregnancy outcome — even if there’s no evidence that bad outcome came from the drug.

But, Schubert said, researchers have learned a lot about how to evaluate a drug’s safety before starting clinical trials since the 1960s.

Sponsored

That’s why she advocates for including more pregnant people in research.

“There are some times when it is maybe riskier,” she said, “but I think when we're thinking through a global health pandemic, it really should be something that we consider automatically.”

A National Institutes of Health (NIH) task force spent the past several years coming up with recommendations for concrete ways to include pregnant people in more research.

Dr. Diana Bianchi was the head of that task force. (She's also the director of the NIH's National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.) She said it’s a contradiction to say, “It’s not safe for pregnant women to participate in research, but it is safe to give [the Covid vaccine] to them.”

“Once again, you leave the burden on the pregnant woman and on her provider to make a decision,” said Dr. Linda Eckert, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington. She’s also on the committee for the Centers for Disease Control that made the policy decision to offer the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines to pregnant women in the U.S.

Sponsored

In Washington state, being pregnant actually moves you up in the vaccine line. A woman who is pregnant and has at least one other underlying condition will be in line soon; pregnant women with no other underlying conditions will be in Phase 2.

“You just have to weigh the risks of acquiring Covid and getting sick with Covid, versus taking a vaccine that you wish you had better data on,” Eckert said.

Researchers tested both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines in pregnant rats and found no harmful effects.

Eckert said there’s also no theoretical reason to believe the Covid vaccines available in the U.S. could harm a developing fetus.

There is no live virus in them, so they can’t infect the fetus. And the mRNA in the vaccines can’t become part of the recipient’s DNA, so it can’t get transferred to the fetus.

Sponsored

Fay, the maternal/fetal physician, looked at all of that and decided, “Those risks of Covid-19 in pregnancy felt a lot worse to me than any potential risks that the vaccine may have.”

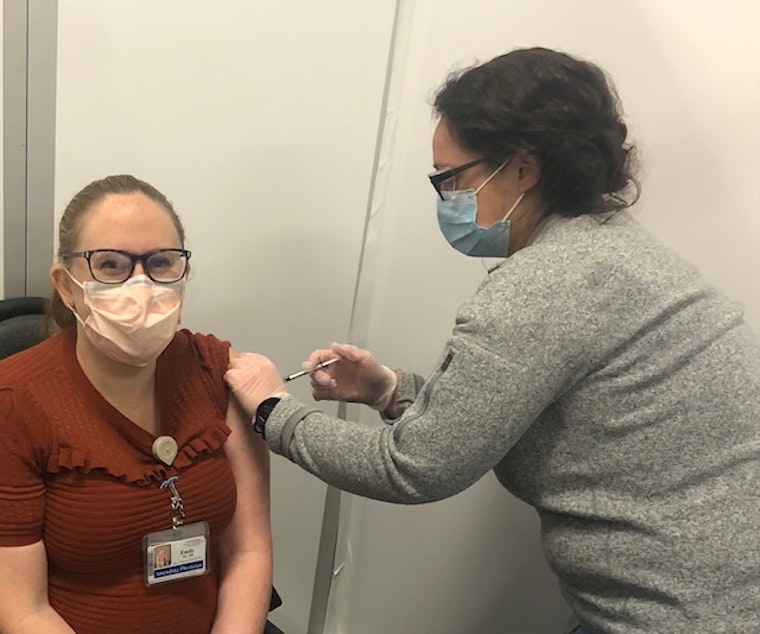

Fay got her first vaccine dose on December 24.

“Beforehand, I was very excited. And then in the few minutes before actually receiving it, I was a little bit nervous,” she said. “There was a ton of excitement in the room.”

Fay has registered for a UW database of pregnant women who’ve received the Covid vaccine. The goal is to track outcomes and, down the road, give pregnant people just a little more information when it comes time for them to make a decision.