PHOTOS: This Alaskan Village Will Be Underwater In 10 Years

I first heard of Kivalina, a sliver of an island in far northwest Alaska, when I was looking for a photo project.

It appealed in part because of this one startling fact: Scientists believe that Kivalina, population 457, will be the first casualty of climate change in the U.S., and that it will be inundated by sea water by 2025. That’s in just a decade.

The people of Kivalina have struggled for years to raise money to relocate or build a bridge should they need to escape during a rough storm. Important because the storms have only grown worse.

But the village also had a personal pull for me. A man named Luke Cole, a friend of my brother’s from law school, represented Kivalina in a lawsuit against the Red Dog mine for polluting the village’s water supply and salmon fishery.

Luke, who co-founded the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, later sought damages from major greenhouse gas polluters. He died tragically in 2009 in an automobile accident.

Brent Newell, an environmental justice attorney at the Center, took over representation of Kivalina. He agreed to let me join him on a trip north last May. “One day, there is going to be a big storm, people are going to die and then everyone will say, ‘Why didn’t we do anything?’” Brent said.

I scraped together every last penny to get up there. I turned to family and friends, who kindly donated money to help pay for the three plane rides it would take to reach Kivalina.

We spent 24 hours in Kivalina. It was May, so the sun was up almost all day, and the children didn’t go to bed until morning. I spent that time photographing, meeting the kids and the elders. Below are the photos I made on that trip.

Most everyone agreed to be photographed – except for a woman who had grown weary of people like me.

“I’m tired of photographers and documentarians coming here, making their stories and their money, while we are left without any change in our situation,” she said. When she said that, I could almost see myself through her eyes, standing there eagerly with my camera like everyone else from the “Lower 48” who jets in and out.

I left determined to at least try to communicate what she is going through and why we all must pay attention to Kivalina. It may be far away, but it is America. If we don’t listen or care, someday we may be facing the same fate.

Kivalina as we flew in. You can see the ice breaking up on the coastline. About 10 years ago, that ice would have been thick, solid and still intact until late May or June. This was May; when we arrived they told us it had broken up within two days. It usually takes weeks to break apart.

It took three planes to get to Kivalina; the last leg is on a small cargo plane. Brent is used to this kind of travel now and has experienced some flights where the storms were so bad, the pilot had to use GPS to land in Kivalina.

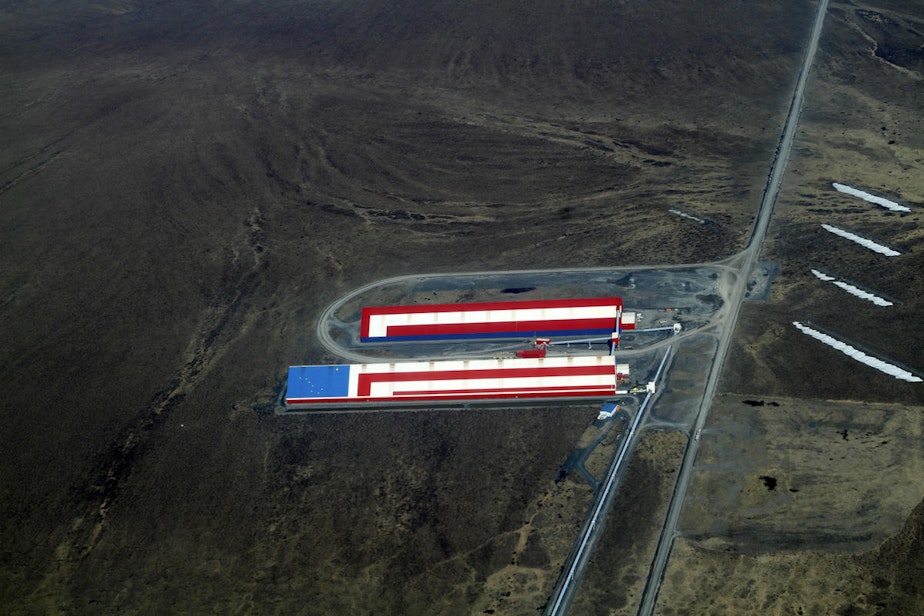

Brent Newell took this photo. He was on the other side of the plane and said, “Do you see that structure with the American flag on it?”

His organization, the Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, was invited to Kivalina to represent leaders in a suit against Red Dog mine. Leaders said the waste dumped from the mine into the Wulik River, Kivalina’s water supply, violating the Clean Water Act.

Red Dog settled and provided Kivalina with water filters until the completion of a pipeline that would direct mining waste away from the river and into the ocean.

Brent and I spent much of our spare time in the home of Lucy Adams, a village elder and elected leader on the City Council. Here she is making him one of Brent’s favorites: her special sourdough pancakes. When I was sitting there I watched them and it seemed like they were both so familiar with one another, like this was almost a homecoming or holiday-like ritual that all families share.

Before we arrived in Kivalina, I asked Brent, “How should I approach everyone? Are there certain cultural things I should know?” He said he approached it like Luke: “Don’t say a lot, just listen.” There were times where we would be sitting in a kitchen or a home and it was silent. I often became very uncomfortable, but Brent was patient. Eventually, something would come out. Usually it was an important feeling or thought about their land or situation.

On this visit, Lucy lamented that the seal skins she uses to make hats and winter boots were becoming harder to work with because the skins did not dry out correctly in the warmer and shorter winters.

This young man introduced me to an artisan relative working on mastodon – whale and walrus bone. Before he introduced me, he posed for this photo in his storage area and showed me the wolf skulls from a recent hunt with his father (on the shelf, left). Even though the ice is changing and it is harder for them to hunt, Kivalina residents still rely on subsistence hunting as key part of their food source.

Brent and I walked to the other side of the island, about a mile down the airstrip and to the garbage dump. One of Kivalina’s retired whaling captains, Andrew Koenig, joined us.

Here, Brent and Andrew stand on sandbags that failed to protect the village from storms and rising sea levels several years ago, which are now being used to protect the landing strip.

The Army Corps of Engineers ultimately built a rock revetment in 2008 that only protects the village (not the landing strip), has a lifespan of 10 years, and does not protect the village from storm surge flooding.

During our walk up to the dump we were greeted by two teenage girls’ joy – they were riding an ATV. The children of Kivalina roam the island, and when the sun stays out, they often play into the wee hours of morning.

At the Kivalina graveyard, graves are precariously close to the waterline. I asked Andrew if I could photograph the graveyard, and he chuckled and said, “Sure, but they’re not going to get up and pose for ya.”

A man stands near the rock wall the Army Corps of Engineers built in 2008. It is likely that the wall will not last beyond 2018.

A girl rides her bike near the rock wall. Residents often see waves crash over the barrier in late fall and early winter before the ice forms. Bad storms flood the garbage dump, landing strip and village.

Brent stands near the Kivalina garbage dump at the north end of the island. Erosion from the sea has broken into the dump and storms are beginning to wash the piles of garbage into the sea.

Standing there, Brent said, “This is America, where’s the EPA?”

Some of the residents even said to me, “Excuse our garbage; we usually wait until it gets warmer to gather it up and take it down to the dump.”

The dump is about a mile away, so they usually load up garbage in carts that attach to their ATVs. I wondered how we would feel if we were all forced to watch our garbage pile up with nowhere else better to put it.

Justin Bieber’s photo in the window of a home. Even amid the polar bear skins and caribou skulls, you are frequently reminded that Kivalina is still in the U.S.

Snow geese were plentiful near Kivalina during our visit. Here Brent and I share snow goose soup with Leroy Adams and his family. Hunters share what they have hunted with the community.

The nearest village north of Kivalina, Point Hope, shares whale. I was lucky enough to eat bowhead and beluga whale that had been part of a recent hunt shared by Point Hope.

Children play near puddles late into the evening. This photo was taken around 11 p.m. I asked them if they had a bedtime, which they seemed to think was a crazy question. When school is out and the sun stays up, the children play until exhaustion gets the better of them.

Lucy Adams’ walls were covered with photographs. I was drawn to this wall in particular, which was filled with different generations of the Adams’ family. Enoch Adams Sr. (now deceased) is on the left; he was a World War II veteran.

This was one of my favorite moments between Lucy and Brent. I don’t remember exactly what was said, but after some somber discussion about the island, Brent made Lucy laugh and the moment was priceless.

A view of the sea near Kivalina in May. The ice had broken up in two days. Normally it would have been solid into June with break-up lasting several weeks during which time the villagers hunt bearded seal. With such thin ice that breaks up quickly, hunting whale in April is increasingly dangerous, while the bearded seal hunt almost impossible.

Suzanne Tennant is a freelance photographer based in Seattle. She was on staff with the Sun Times Media Group/PioneerPress in Chicago from 2006-2011. Her work has also appeared in The Chicago Sun Times, The Chicago Tribune, UPI, The Post Tribune, Hemispheres and Sun Publications.

The Seattle Story Project: First-person reflections published at KUOW.org. These are essays, stories told on stage, photos and zines. To submit a story - or note one you've seen that deserves more notice – contact Isolde Raftery at iraftery@kuow.org or 206-616-2035.