Not everyone makes peace with their dad. My teacher inspired me to try

Sometimes it feels like we’re missing something in our lives. And sometimes we find what we’re looking for when we least expect it. Kind of like what happened to me.

I go to a small alternative high school called Interagency Southwest. Teachers there work with kids who are suspended, expelled or just looking for a different environment, like me. Regular high school was not working for me. Too many kids for somebody’s who’s not a people person. Shawn Kamp is a new teacher there. When he first started talking to me, he’d tell me about scholarship opportunities and ask me about my future, like a lot of teachers do. But I could tell this guy genuinely wanted to help me out.

One time, he noticed my worn-out boots that I’d been wearing and he actually offered to give me some of his own boots.

And since I had to interview somebody for this story, I decided to interview him. In the interview, I asked him about teaching experiences and why he became a teacher. But when we started talking more about his upbringing, he told me a story I was not expecting.

Mr. Kamp grew up with his mom, two older sisters and one older brother. His dad wasn’t around. Mr. Kamp’s mom struggled making good money and worked a lot, so he had a lot of free time. He got to do whatever he wanted.

Sponsored

He wasn’t a bad kid, but one time when he was 13, he and a couple of his friends broke into their school cafeteria and got caught with stolen ice cream. Youthful shenanigans, right? Well, Mr. Kamp actually went to juvenile jail for it. He was only there a couple days, but it really impacted him. When he got out, he knew he’d have to meet his probation officer.

"I thought that probation officer was going to yell at me like all these good teachers do and he didn't," he said. "He was just like, 'Yeah, I don't know. Don't break the law again and you won't go to jail again. Break the law, you go to jail. See you in a month.'

"I just knew that he didn't care and that bothered me because I wanted to be a better person. I just said, 'When I grow up, I want your job. I want to work with kids like me. But I want to care.'" The author's school, Interagency Southwest

Eventually, that's what he did. He joined the PeaceCorps and worked in a bunch of different programs. Now he's at my school.

I wanted to know more, so I went with the flow and we started talking about his dad. "The first time I ever met my dad was in jail," he said. "It was in a penitentiary, actually." Mr. Kamp’s dad went to prison for robbing a bank when he was still too young to remember him.

Sponsored

He would visit his dad, but he never really got to know him personally until Mr. Kamp was about 35 and he learned his dad was in the hospital, dying.

"You hear in the movies about unplugging life support to let someone die?" he started. "Well, they did that to my dad. I went down to see him. I expected him to be dead. He actually woke up and was okay."

He didn't only wake up. He was talking too. "And he actually decided he wanted a family reunion." Well, his dad saved up some money selling cigarettes in prison so they threw together a little thing and got the whole family together. But Mr. Kamp told me at the family reunion, he got the impression that his dad was really lonely.

"I made the decision after that to go down and visit him," he said. "He was living in Tacoma, and I saw him the next month, the next month, and before I saw him the third time, he died.

"It's a weird story 'cause my father almost died, and when he lived another four months, I got to know him really for the first time in my life."

Sponsored

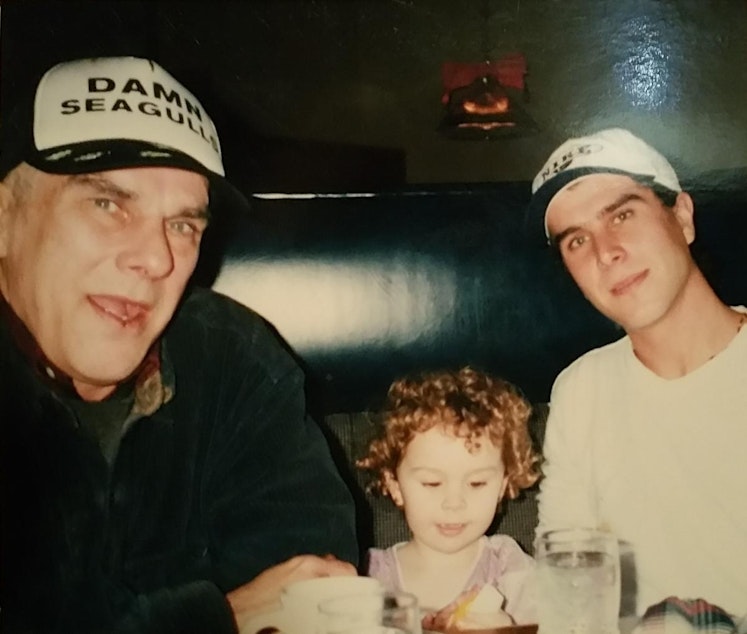

Mr. Kamp learned that his dad also grew up without his father, because he died in a logging accident. His closest brother died too. Mr. Kamp didn’t know any of this until he really got to connect with his dad over those last four months. "That's a huge, huge blessing in life, to have your peace with your father," he said. "He's an important person in your life. Whether he's a good person or a bad person, he's always important.

Mr. Kamp turned to me: "I don't know your story with your father," he said, "but I think we can look around and we know that hurts people, to not have your father in your life." At this point the interview felt more like a conversation, so I told him about how my dad cheated on my mom here and there, and they split up when I was young. As I grew older, my dad and I grew apart.

And Mr. Kamp’s right. I don’t think about it that often but when I do, it does hurt.

"I think your story and my story are not unique," Mr. Kamp said. "It's not unique, but it's personal." After talking more, Mr. Kamp even gave me some advice about my own situation: "I don't hear you asking for advice, but I'll give you a little bit. It's okay to be the bigger person. Sometimes that feels unfair, but it's also fair that you get to be that person. No one is stopping you from being a better person.

Sponsored

"And I see you step into that, from what I know of you, Nate, and that's a cool thing." I barely knew Mr. Kamp and his story made me realize that it's easy to forget that nobody's born a bad person. Like Mr. Kamp's dad, my dad made some bad choices and he's not really in my life right now, but that definitely has not ruined my life.

But I can be the bigger person. I can take some initiative into trying to connect with my dad. Not everyone gets that opportunity, and I don't think I would have truly understood that without Mr. Kamp's advice and his story. So thanks, Mr. Kamp.

Ed note: Since writing this story, Nate has gotten in touch with his dad.

This story was created in RadioActive Youth Media's 2017 After-School Workshop for high school students at New Holly in partnership with Seattle Housing Authority.