New political maps will determine Washington state’s future

When Yvette Joseph, a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, ran for the 7th Legislative District in northeast Washington in 2004, she faced a structural disadvantage due to where the district’s western border line was drawn.

“I looked and was sort of shocked that it ran right through the reservation. So essentially, half of my family could vote for me and the other half could not,” she said.

It may seem like an obscure act of cartography, but how Washington state’s political maps are redrawn this year will help determine who gets elected and, in turn, the future of the state.

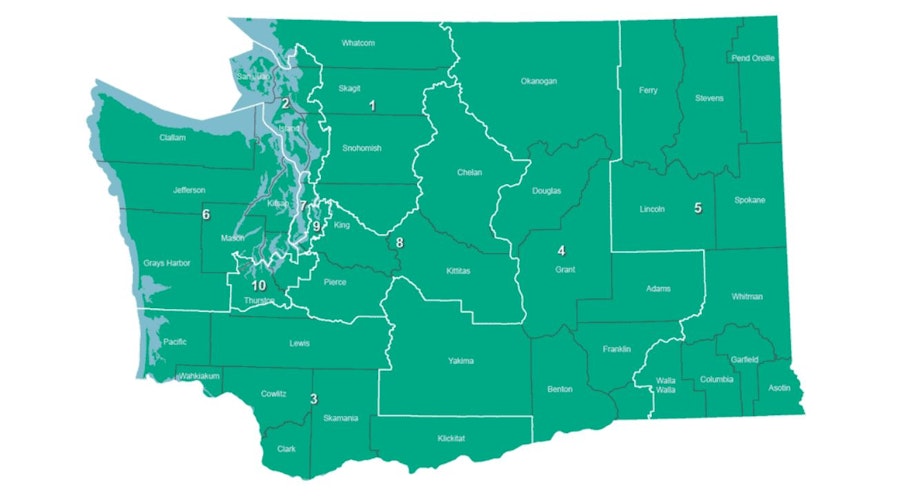

The maps are remade every 10 years after the Census in a process called “redistricting,” in which the boundaries of our state’s legislative and congressional districts drawn.

After the 2010 census, district maps were changed, but the Colville reservation remained divided. Yvette Joseph said that meant that when the Chairman Joe Pakootas ran in 2014 and again in 2016 against Republican Cathy McMorris Rodgers to represent the 5th Congressional District, many on the reservation could not vote for him.

This year some Washingtonians including Joseph are demanding change.

“I am very hopeful that the Colville Tribe is going to fight it and convey their concerns to the redistricting commission,” Joseph said.

Our state’s district maps are drawn by a "redistricting commission" that includes four voting members who are appointed by lawmakers in Olympia. Two are named by the top state Democrats and two by Republicans. A fifth, non-voting chair is appointed by the other commissioners.

Sponsored

This type of bipartisan redistricting commission is often seen as a vast improvement over other states where district maps are drawn by whichever party is in power in the state legislature at the time. That often results in the creation of strange-looking districts that are designed to make sure the party that's in power stays in power.

Lisa Marshall Manheim, a law professor at the University of Washington, said our system is a big improvement over that form of “partisan gerrymandering." But she also said in our process map lines are drawn by the commissioners to “favor the two political parties.”

“They may not take into adequate account the interests of other groups like certain racial or ethnic minorities, or the interests of certain communities that come together in different ways," she said.

There are signs that the concerns of underrepresented groups may be front and center this year when the maps are redrawn.

April Sims is one of the Democrats serving this year, who is also Secretary Treasurer of the Washington State Labor Council, said her top priority will be to "make sure that the communities that are impacted by those decisions have an opportunity to participate in the process."

Sponsored

Brady Walkinshaw, another Democratic appointee this year, sounded a similar note.

“This should be an extremely public, daylit, sunlit process that that the public is able to participate in and give input on,” he said.

Republicans on the new commission may be willing to work with Democrats to make sure more groups like the Colville are able to vote together.

“Being able to say I'm an Issaquah voter, I’m a Colville voter, I'm a Seatac voter is a pretty big virtue,” said Paul Graves, a former state lawmaker who was appointed by Republicans to the commission for 2021.

In addition, the League of Women voters and progressive groups are working to ensure more voices are heard by the commission.

Sponsored

All this suggests the Colville could see a change this year. The same may be true for other groups including the Yakama Nation in central Washington, which has faced similar issues with lines being drawn through the reservation.

There’s no guarantee that changing maps alone will lead to different outcomes in terms of policy or representation. After the 2010 Census, the 9th Congressional District was redrawn to be the state’s first majority-minority district. But the 9th is still represented by a white male, while the neighboring 10th Congressional District, which is majority white, just elected the first Black person to Congress from the Pacific Northwest.

Another factor in our our bipartisan redistricting system is that deals are often cut to make sure most incumbents are less likely to lose elections.

Tim Ceis, former deputy mayor of Seattle, who served on the last commission as a Democratic appointee, said that’s exactly how he and Slade Gorton, former Republican U.S. senator, approached the job.

“Slade and I, in particular, talked about not going after incumbents, that there was no need to do that,” Ceis said.

Sponsored

Lura Powell, who was selected to fill the 5th, non-voting commission seat in 2011, said she wasn’t present at any of the meetings where that sort of horse-trading occurred between partisan appointees. And that was by design.

“We basically paired up the two state Senate-nominated commissioners and the two House ones, because if more than two were in a meeting it became a public meeting, and they wanted to have at least some private discussions,” she said.

In other words, the commissioners could avoid triggering state open meeting rule requirements, and were able to cut deals behind closed doors without public scrutiny or record of what was said.

Ceis said that bipartisan process in 2011 was no secret then or now.

The commission tried to make nine congressional seats safer for the incumbents, and a single competitive district. (As it turns out that that single district, the 10th, has become a safe seat for Democratic incumbent Suzan DelBene).

Sponsored

The first meeting of the 2021 Redistricting Commission will be held starting at 4 p.m. on Wednesday, January 27, which you can tune into on TVW.