‘My first-grade teacher was my first bully.’ More allegations surface against Seattle teacher

After a KUOW investigation revealed a Seattle elementary teacher’s history of discipline for physical abuse, eight more individuals and families have come forward with similar stories in Martin McGowan’s classroom.

It raises new questions about why some reported incidents don’t show up in the teacher’s discipline record.

Roman Harto was 6, rummaging through a classmate’s crayon box for a purple. His teacher saw him, he said, then grabbed him by the arm and dragged him over to a desk. Then his teacher made him stay in from recess to sort crayons.

The teacher, Martin McGowan, also regularly humiliated him in front of the class, said Harto, now 23. Harto is dyslexic, and his spelling tests were peppered with mistakes that McGowan would routinely use as examples for the rest of the class, “like ‘Roman’s not doing a good job,’” Harto said. “It was horrible.”

“My first-grade teacher was my first bully,” Harto said.

Stu Smith, now 25, recalled being dragged by the ear by McGowan when he was in first grade. This year, his son is in McGowan’s classroom at West Woodland Elementary in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, and also reportedly had his ear yanked.

Many other stories of abuse in McGowan’s classroom have emerged since a recent KUOW story about his disciplinary history for using corporal punishment, including ear-pinching and neck-grabbing.

One boy told his mom that McGowan pulled him by the ear, then shoved his head onto his desk. Another girl said she saw McGowan yank a classmate up to standing by his ear.

Current and former West Woodland families contacted KUOW to report eight new abuse allegations against McGowan after an earlier story detailing four incidents for which he had been disciplined or counseled.

Of the new accusations, six involve corporal punishment. Four involve repeated verbal or emotional mistreatment.

McGowan was placed on paid administrative leave on February 14th following KUOW’s first report. Seattle Public Schools has informed him it is investigating multiple new allegations of misconduct.

The allegations reported to KUOW span 20 years and at least three principals. Only some of the cases are detailed here. Some parents wanted to keep their stories private out of fear of retaliation by the school administration.

Many parents said they complained to school leaders at the time. But after at least two decades of abuse allegations involving McGowan, only two disciplinary letters appear to remain in the teacher’s file: a written reprimand from 2006 for hurting a child’s neck, and another written reprimand from 2019 for pinching a child’s neck and ear.

KUOW has learned of at least two other disciplinary letters that appear to be missing from McGowan’s file.

KUOW sent McGowan and his union representative a detailed list of the new allegations against him. Neither McGowan nor the union responded to a request for comment.

//

[Read the earlier KUOW story about Martin McGowan’s abuse of students, and how the district responded.]

Despite multiple documented incidents of abuse, McGowan maintained a reputation among many as a dedicated, fun-loving teacher: He dressed in tie-dyed shirts, rewarded students with gummy bears, and let kids pelt him with water balloons at the end of the school year. Parents said he took the time to get to know each student, and them, too – he asked them to volunteer in his classroom, and invited them out on his sailboat.

Last year, Seattle Public Schools disciplined McGowan for hurting a child’s neck and ear, then notified the state education department, as required.

When a school district attorney notified West Woodland families last month that the state had opened an investigation into McGowan’s history of misconduct, for which he could temporarily or permanently lose his teaching license, some parents rallied support for the teacher.

“You can be an advocate for him,” Melissa Rauda emailed a long list of other parents, and encouraged them to send letters on McGowan’s behalf to the district legal department and state Office of Professional Practices.

Rauda wrote to state investigators that she was “saddened by the investigation of one of West Woodland Elementary’s greatest teachers.”

“I feel strongly that Mr. McGowan was falsely accused,” Rauda wrote, due to “an overreaction by both the child and the parent.”

//

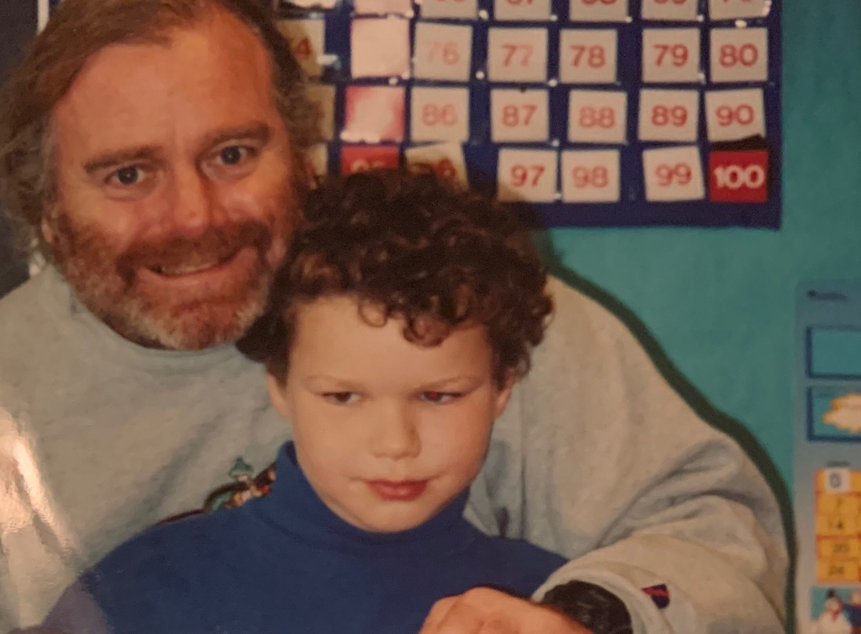

Last fall, Stu Smith was apprehensive when his son Alex was assigned to Martin McGowan’s first-grade class.

Smith, who is 25, had McGowan as his first grade teacher in 2000. Smith said he had a “very vivid memory” from a show-and-tell activity in the class two decades ago.

Smith was partnered with a girl who was to guess what he was holding in his hand. The girl couldn’t figure it out, Smith said by text message, “so I finally just showed her.”

McGowan “saw me do it and dragged me by the ear,” Smith said.

Smith shared his concerns with his wife, Angelea, who reassured him. She’d seen McGowan with his students, and he seemed to her like a caring teacher. People can change a lot in 20 years, she said.

Recently, the Smiths received an email that shattered that notion.

A mom wrote to share something her daughter had told her days earlier: That “Mr. McGowan had pulled Alex up by his ear.”

The mom wrote that she had assumed her daughter was exaggerating, but after reading the KUOW story, she believed her daughter’s account.

The mom said she had informed the assistant principal as well. “I’m sorry I did not realize sooner this was something I needed to inform you of,” the mom wrote to the Smiths.

When they asked their son about the alleged incident, the Smiths said, he denied being pulled by his ear, or said he didn’t remember. Their son struggles with anxiety, they said, and the whole conversation got him worked up.

“Alex keeps thinking he’s in trouble when he talks to us about it, so we can’t really get any info about it out of him,” Stu Smith said.

“I’m just pretty upset that this has been going on for 20 years and nothing has been done at all except a slap on the wrist” to McGowan, Smith said.

A district investigator is now looking into the allegation that McGowan pulled Alex’s ear.

//

Corporal punishment in schools, defined in state law as “any act that willfully inflicts or willfully causes the infliction of physical pain on a student,” has been illegal in Washington since 1994. Ear-pulling, hand-slapping and neck-grabbing are all clearly off-limits under this law, said education attorney Jinju Park.

School staff are mandated reporters, and administrators are legally required to report physical abuse of students in school to police. There is no indication in McGowan’s file that West Woodland administrators ever called the police about any incidents involving him.

Last year, after McGowan was found to have pinched one boy’s ear and grabbed his neck, Principal Farah Thaxton told the boy’s parents in an email that she had not reported the incidents to the police. “As the parents you have the right to call both CPS and the police regarding the issue,” Thaxton wrote.

At a meeting last week for West Woodland parents, the boy’s father asked human resources chief Clover Codd whether corporal punishment should be reported to the police.

Codd paused. “I think it depends on the type of corporal punishment,” she said. “But I personally think it should be reported. Does it always get reported? I’m not going to sit here and tell you that it always gets reported,” Codd said.

When a school district has reason to believe a teacher has committed serious misconduct, like abusing students, the superintendent is required by law to report the teacher to the state Office of Professional Practices for investigation and possible action against the teacher’s certificate.

Despite numerous instances where McGowan was either disciplined for misconduct, or where administrators say he acknowledged hurting kids but was not disciplined, only one time did Seattle Public Schools notify the state.

In that case, last year, the district waited months after the discipline before notifying the state. A state investigation is currently underway.

//

In 2012, another boy was having a rough first-grade year in Martin McGowan’s class.

At the mother’s request, we are using her middle name to protect her son’s privacy.

After school one day in late February 2012, Anne’s son seemed dejected but wouldn’t explain why.

Then he told Anne that Mr. McGowan had become frustrated with him in class and had pulled him by his ear across the room. The boy said his teacher then ordered him to put his head down on his desk.

When the boy did not comply, he told his mother, McGowan shoved his head down onto his desk.

“[He] told me that and just started sobbing,” Anne said. “I have never seen him be so upset in his entire life. I was shaking. I just felt so helpless to go back in time and make that not happen to him.”

At the time, Anne recorded her son recounting the incident, and emailed it to the school counselor. She provided KUOW a copy of that recording.

Anne’s son’s therapist confirmed in an email that the parents had told him about the ear-pulling and head-shoving, and that the parents had met with the principal about the incident.

At that meeting with then-principal Marilyn Loveness, Anne said, “It was mainly us doing the talking. Just repeatedly saying, ‘What's going to happen with [McGowan]? How can we know our son is safe?’”

Loveness said she would ensure that McGowan’s classes received outside observation, Anne said, and that the teacher would apologize to her son.

“Then Loveness assured me that he would get a disciplinary letter in his file,” she said.

There is no evidence of this letter in disciplinary records that Seattle Public Schools has provided to state investigators regarding McGowan, or in response to public records requests from parents.

Anne never saw a discipline letter, and she now wonders whether the principal ever issued it, as promised. “I am just so, so angry right now,” she said.

“I feel like if I had done more, if I had gone to the district myself, that maybe there would have been an investigation in 2012, instead of now,” Anne said. “I absolutely feel like he was being protected and enabled to keep hurting kids.”

It’s unclear whether this letter was ever written, or whether it may have been removed from the teacher’s file.

Another disciplinary letter, from 2005, was also cited in a 2006 written reprimand. That 2005 disciplinary letter also appears to be missing from McGowan’s file.

In an email to McGowan regarding a 2019 written reprimand, Assistant Principal Kelly Vancil told him that the teachers union “contract does provide you the opportunity to remove the reprimand from your personnel file” after four years.

In fact, state law bars removal of all disciplinary records regarding verbal, physical or sexual abuse.

When KUOW asked about the district’s practices regarding removal of discipline records, spokesperson Tim Robinson cited the teachers union contract, which says that abuse records cannot be removed.

Seattle Public Schools chief of human resources Clover Codd has said that, as part of a “transformation” of her department, the district is moving to an all-electronic record-keeping system for disciplinary records and other personnel files.

Neither Loveness nor Vancil replied to requests for comment for this story.

//

In April, 2018, one of McGowan’s first-graders told his parents that his attention wandered that day as the teacher was addressing the class. “I was looking out the window, and then he slapped me” on the hand, the boy told KUOW.

The boy’s parents asked to remain anonymous out of fear of retaliation by school staff.

The boy’s mother met with Principal Thaxton, Assistant Principal Vancil, and McGowan to discuss the incident. McGowan apologized to the student and his parents, they said, but nothing else seemed to come of the matter.

“They have a tendency to minimize the issues that go on at their school,” the mother said.

The assistant principal wrote about the hand-slapping incident in a 2019 written reprimand to McGowan for another series of incidents in which he was found to have pinched a different child’s ear and neck. Referring back to the 2018 hand-slapping incident, Vancil reminded McGowan that “We met with a parent and you agreed that you should not have intervened in the way that you did and you apologized” for slapping the child’s hand.

There is no indication that McGowan was disciplined for slapping the child’s hand. “He has no right to put his hand on nobody’s child, period,” the father said.

Principal Thaxton did not reply to KUOW’s request for comment on this story. But at a meeting last week for families at West Woodland, Thaxton said that the situation is heart-wrenching. “I can’t sleep at night,” Thaxton said.

“We have failed,” Thaxton said. “I take responsibility that we have failed your children in situations like this.”

//

Margaux Jones said she still sees the negative effects of first grade in Mr. McGowan’s class three years ago on her daughter River, who is now in fourth grade at West Woodland Elementary.

McGowan required students to read aloud in front of the class, and Jones said when her daughter “had a difficult time doing that because of her dyslexia, he basically shamed her.” Other parents of three other children with learning disabilities told KUOW their children received similar treatment from McGowan.

When River hadn’t finished her work midday, “I would have to stay in for lunch,” she said, and would only end up with time for a few bites. “I remember her coming home and her lunch wouldn't be eaten,” Jones said. McGowan “did tell me when we had our meetings that he would keep her in for lunch or recess,” Jones said, despite her objections.

River said her primary memories of first grade are of “a bunch of yelling” from her teacher. River said she remembers “trying to hold the crying in, and then when I'd get home, I'll let it all out.”

The situation was taking a toll on how River saw herself, Jones said. “Her self-talk was becoming, ‘I’m not a good student. I can't learn. I'm not as good as the other kids.’”

Jones said she complained to Assistant Principal Vancil and to River’s special education teacher.

“I would say to them, ‘You can't shame a kid into learning,’” Jones said. “I remember telling them that we've got a problem when a kid cries every day and doesn't want to come to school. That's not what a kid should be doing at first grade,” Jones said.

Vancil said that they were doing what they could to help River, Jones said.

Because so many families raved about McGowan, it was isolating to be having such a bad experience, Jones said.

“It became, like, ‘Well, what's wrong with your kid? Everybody else here loves him,’ you know?” Jones said.

Although classmates talked about their trips on McGowan’s sailboat, River said her teacher never invited her mom and her on his boat. “I kind of felt sad,” River said.

Jones said the low self-esteem River developed in first grade carried over the following year.

“She went into second grade with the self-talk every day of ‘I can't get this. I'm not going to understand. I'm stupid. I'm not like the other kids,’” Jones said. Some of that self-talk still lingers, she said.

While McGowan never physically hurt River, her mother said, the experience left a mark. “Those are the scars you don’t see,” Jones said.