Mild quake shakes Western Washington. What should we do to prepare for something bigger?

Did you feel it Sunday night at 7:21? Some did, others had no idea. That's when Western Washington experienced a 4.3 magnitude earthquake. It was centered south of Port Townsend, near Marrowstone Island, about 35 miles below the Earth's surface.

There was no tsunami risk, and there haven't been any reports of significant damage. So crisis averted, for now.

Things were different 22 years ago when the 6.8 magnitude Nisqually Earthquake hit, causing $4 billion in damage and injuring 400 people. The Nisqually quake originated from a shift in the same Juan de Fuca Plate and occurred at the same depth, but in a different location, 11 miles north of Olympia.

So, why did this quake cause so much less damage and what should Washingtonians do to prepare for similar or stronger quakes in the future?

University of Washington professor Harold Tobin directs the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and is Washington's state seismologist. Tobin felt Sunday's quake. He said the mild shaking made him jump up from his living room couch, and should serve as a wake-up call.

"It wasn't damaging, but it's a reminder that we live in an earthquake-prone, seismically active region. It's not a matter of if but when," Tobin said. "So all the preparation we can do from an individual level right up to all the levels of government are tremendously important."

Sponsored

Tobin said it would take a mid-5 or higher magnitude quake to cause damage in Washington state, but the latest quake serves as a good reminder that they don't give advance warning, so Washingtonians have to be ready.

Where did this quake originate?

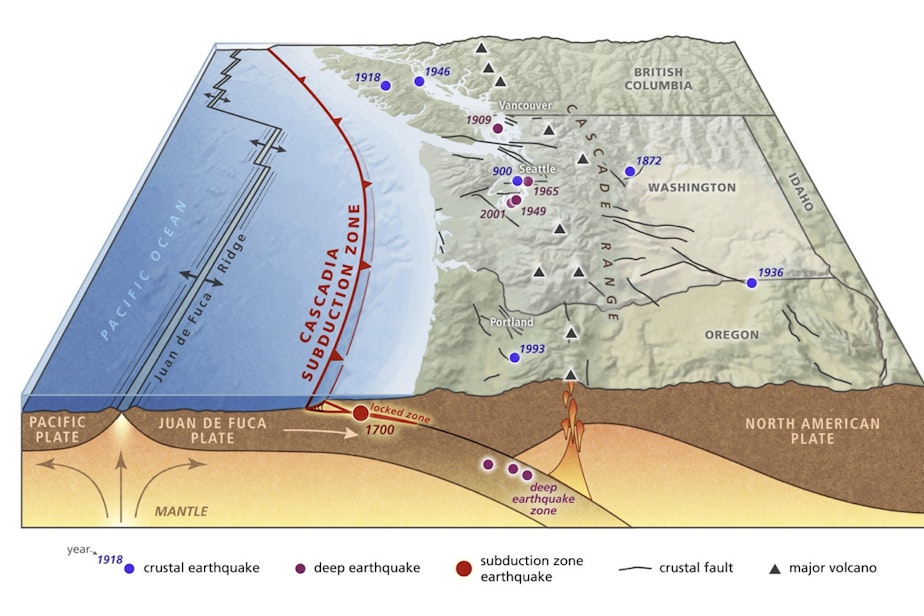

Tobin said Sunday's quake was based in the Juan de Fuca Plate, a relatively small tectonic plate that is subducting, shifting down, beneath the larger North American Plate at what scientists call the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

How often does this type of quake happen?

Western Washington experiences mid-4 magnitude earthquakes every few years. The last, the 4.6 magnitude Monroe Earthquake, was in 2019. Tobin said it would take a mid-5 or higher magnitude quake to cause serious damage in the region.

Sponsored

Why didn't I get a ShakeAlert warning on my phone?

Tobin said that answer is really interesting. He said automated monitors identified the shaking immediately, and made the determination that it wasn't strong enough to warrant an alert. The quake would have needed to be at least a magnitude 4.5 to trigger one.

Why did one person in Belltown feel it, but another on Capitol Hill didn't?

Tobin said while the quake was likely felt more strongly in Port Townsend than in Seattle, a quake at that depth has a wide scope. He said nobody is especially close to it, even at the epicenter, when it's 35 miles away.

"While an earthquake has one magnitude and generates one set of waves, the way they interact with the kind of soil layers and the surface environment and the buildings that you're in really varies," he said. "From neighborhood to neighborhood, from house to house, literally even room to room within a house, you might feel shaking a little bit stronger, or a little bit weaker. What I can say too, is that the magnitude of this earthquake, 4.3, the shaking was pretty light. So that's why it's kind of at that that edge between noticing it and not noticing it."

Sponsored

What do we need to do to prepare for a bigger quake?

Tobin said the relatively mild event is a good reminder of what to do in a stronger quake. He shared these recommendations for when the shaking starts.

"Move away from any heavy objects that could fall on you like a big bookshelf, or a chandelier or something, and instead try to get under something sturdy, like the dining room table, whatever is handy," he said. "Don't try to run out of the house, don't stand in the doorway where a swinging door could hurt you."

Make sure to have a ready supply of food, water, and flashlights, and a plan for where to meet if your family is separated and can't communicate.

"After a major earthquake happens, most of us would not try to leave the city immediately, unless there really were absolutely no services at all," he said. "A lot of us I think could be faced with essentially camping in place for a little bit of time, and that's the kind of preparation I think is useful."

Sponsored

It's important to recognize whether your home has fundamental structural issues and pursue remedies.

"There are thousands of buildings in Seattle that are probably not up to snuff from modern earthquake standards," Tobin said. "The city is planning to address this with some new ordinances. I haven't seen any text yet on exactly what that will be. I would really emphasize that we know this is a genuine problem. Retrofitting buildings, and building new buildings up to modern seismic code, can really be the difference between injuries and deaths in those buildings."

Tobin encouraged people to keep pressure on their elected leaders and building owners to follow through on maintaining building standards and retrofitting older buildings so they can survive more serious earthquakes.

How do our quakes compare with California's?

Tobin said, unlike the San Andreas Fault in California, the Cascadia Subduction Zone stores up the strain a lot longer and then result in earthquakes that are potentially quite large, but much more infrequent.