Life after a hate crime: the recovery of DaShawn Horne

“H

omie. Get the fuck up, homie.”

The voice behind the iPhone camera is raspy, like the person speaking had just exhausted his voice screaming.

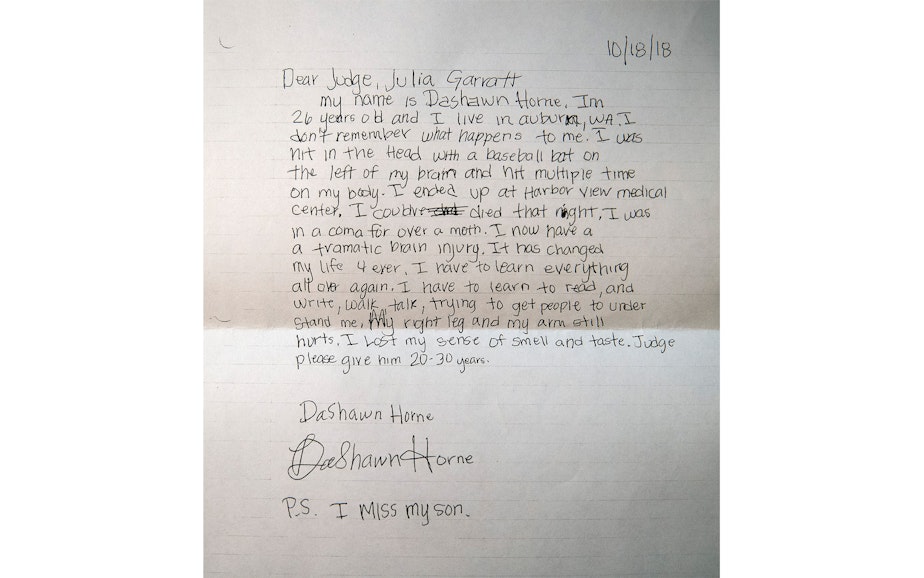

The video shows 26-year-old DaShawn Horne, lying face down on a pile of rocks, unconscious, blood streaming down his face.

“That’s what happens to these n————rs out here, huh,” 18-year-old Julian Tuimauga continues, his voice ratcheting up with intensity. “THAT’S WHAT HAPPENS TO YOU N————RS OUT HERE, BOY.”

From the side of the frame, the weapon Tuimauga used to beat DaShawn over the head within an inch of his life appears: a 32-inch aluminum baseball bat.

Police thought they were responding to a homicide. But when they arrived, DaShawn was still breathing.

The attack lasted a matter of minutes but left DaShawn in a coma at Harborview Medical Center for six weeks. Over a year later, he’s still recovering.

Hate crimes have been on the rise since 2011 in Seattle. In 2017, there were 234 hate-motivated assaults in the city, almost double from the previous year. According to the FBI, African-Americans were the most targeted both years.

Hate crimes are increasing in Washington state, too. Nationally, hate crimes increased by 17 percent in 2017, while Washington saw a 32 percent increase.

But after news headlines on hate crimes fade, victims and their families live with their assaults much longer.

DaShawn Horne was one of the first victims of 2018.

On January 19, he met a woman at a Seattle club. He went home with her, to her family’s house in Auburn, and spent the night. The next morning, DaShawn left the home to get into his Lyft. As he was leaving, the woman’s brother, Julian Tuimauga, attacked him.

After the attack, Tuimauga went back into the house, broke down his sister’s bedroom door and called her a whore.

Police interviewed the Lyft driver who witnessed DaShawn’s attack. The driver said he overheard Tuimauga saying, “This is what happens when you bring black people around here.” The Lyft driver called 911.

At the hospital, DaShawn was taken straight to the operating room. His pupils were dilated and fixed – a sign of a severe increase of pressure within the brain.

But there were positive signs, too, such as a reaction to a painful stimulus, that neurologic function remained.

Surgeons removed part of DaShawn’s skull to relieve the pressure and to drain the blood clotting around his brain. The operation left a dent on the left side of his head.

When DaShawn’s mother LaDonna Horne arrived at the hospital, she could have fainted.

“Just to see him, it was unbelievable,” she said. “The machine was breathing for him.”

LaDonna, who worked at another hospital, refused to leave her son’s side and slept on a small cot in the corner of his room for months. Her co-workers donated time off so that she could be there with her son.

“I decided that I wasn’t going back to work,” LaDonna said. “I didn’t care what was going to happen, but I knew that I was not leaving DaShawn’s side.”

Still in a coma, the surgeries continued. DaShawn underwent a tracheostomy, a hole was surgically placed through his trachea so he could breathe through a tube connected to a ventilator. They inserted a feeding tube, and another tube into an artery of his heart for a daily blood draw.

At the end of January, DaShawn contracted pneumonia. A couple of weeks later, MRSA, a contagious bacterial infection, took hold in his lungs.

Family members wore gloves, masks and protective suits when they visited. DaShawn underwent yet another surgery to drain the infected fluid that had collected between the lining of his chest wall and his lungs.

Meanwhile, LaDonna’s life became a tornado of phone calls with insurance companies, law enforcement, attorneys, doctors, nurses and family members.

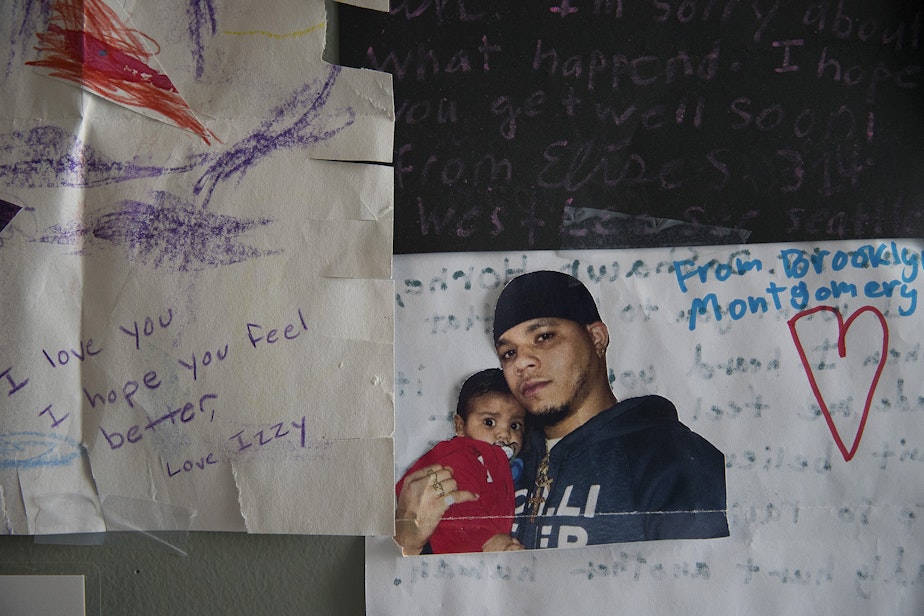

Two weeks after the attack, DaShawn’s friends and family members held a candlelight vigil outside of Harborview. LaDonna held DaShawn’s 1-year-old son Deion as the community gathered around them in support.

At the hospital, LaDonna fasted off and on. She read the Bible, blessed DaShawn’s body with blessing oils and sang worship and gospel songs. Every day, she read a daily devotional to him. “I cried every day, every night, screaming why,” LaDonna said. “I would go to my car and vent and scream and cry and pray and praise god and cry all over again.”

As LaDonna saw it, DaShawn’s attack—and his subsequent recovery—was an act of God.

In the weeks after the attack, doctors and nurses debated whether DaShawn could hear the conversations happening around him. His eyes remained closed; he looked asleep. There was no way to know for sure.

But one day in mid-February, a therapist asked DaShawn to hold up five fingers. To everyone’s surprise, he did. It was the first time DaShawn demonstrated an ability to comprehend what was happening.

“I was like, what? He can hear you?!” LaDonna recalled.

After that, LaDonna made sure that any conversations that took place in DaShawn’s hospital room were positive.

Before the surgery to drain the fluid from his lungs, LaDonna told DaShawn that he had the whole world praying for him. He raised his head up. To LaDonna, this meant that he was listening. “I said yeah, the whole world,” she said.

Then, on March 3, DaShawn opened his eyes.

DaShawn was awake, but unable to speak. His eyes followed people as they moved around his room, but it was unclear how much he understood.

On March 19, two nurses were changing DaShawn’s clothes when his leg bumped up against the railing of the hospital bed. “Let my leg down, let my leg down!” DaShawn said. Those were his first words that could be understood since the attack.

LaDonna was overjoyed. “Did you hear that?!” she asked the nurses. They repeated the words back to her.

As DaShawn started speaking, it became clear that he was suffering from aphasia, a communication disorder that impairs ability to process language and express speech — a result of the brain injury. He would often get frustrated and smack his lips together when what he was trying to say didn’t come out the way he intended it to.

Occasionally, DaShawn would call people by names that weren’t theirs. Or he’d see someone in the hallway he thought he knew, but had never met.

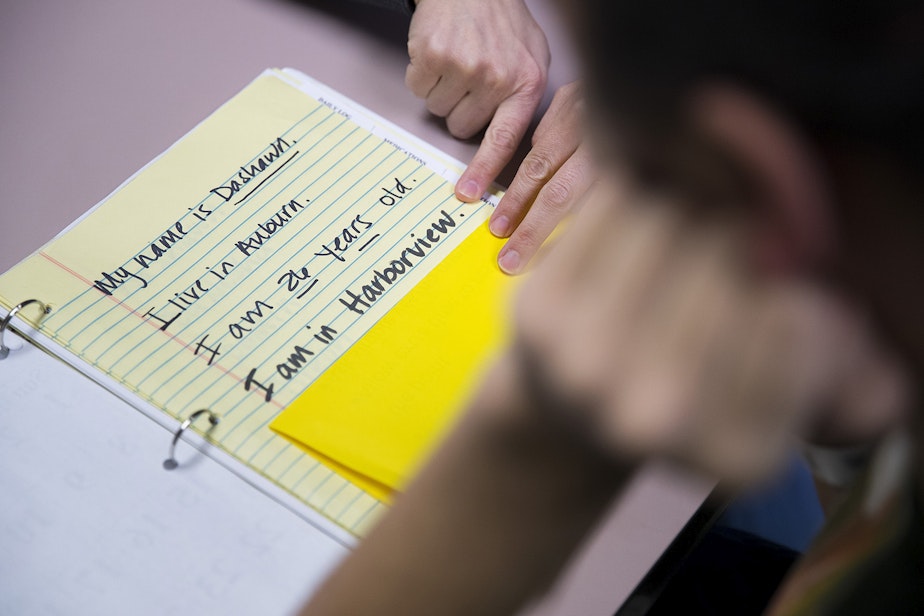

Every day, during speech therapy, his therapist had him repeat the same series of statements: “My name is DaShawn. I live in Auburn. I am 26 years old. I am in Harborview.”

Before the attack, LaDonna described her son as happy and generous – and someone who frequently joked around. He worked as a mail handler for the U.S. postal service and loved his son, Deion. “That was his number one person in his life,” LaDonna said.

But in the early stages of recovery, it was difficult to tell what DaShawn was thinking or feeling.

LaDonna noticed his personality coming back slowly. She still worried what would happen if he caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror. The first time she noticed him looking in the mirror, she stood in front of it to block his view.

In April, DaShawn asked his physical therapist to remove the belt that was used to stabilize him. “It’s messing up my swag,” DaShawn said.

Soon, DaShawn walked laps around the fourth floor with a cane, and then on his own with his physical therapist holding onto his belt. His mind was coming back, too. DaShawn could remember the names of his family members and write them in a list: Dominic, Da’Nesha, LaDonna, Deion, Monica.

At the end of April, the process to discharge DaShawn from the hospital began, but his recovery was far from over. He would require 24-hour care and would still need to travel to Seattle from Auburn several times a week for rehabilitation appointments, brain scans and checkups.

But leaving the hospital was momentous. DaShawn pumped his fist as his nurse Derek wheeled him through the halls toward the exit. When they arrived at the West lobby, DaShawn got out of his wheelchair and walked out of the hospital on his own.

“I think I finally just took a deep breath,” LaDonna said.

They had been at Harborview for 103 nights.

At their home, DaShawn’s friends had helped move furniture to convert the den into his new bedroom on the first floor.

“DaShawn, what year is it?” LaDonna asked.

“2010,” DaShawn answered.

She corrected him, as she always did: it was May 3, 2018.

For the next four months, DaShawn’s 24-year-old sister Da’Nesha became his round-the-clock caregiver. She came home from Eastern Washington University, where she was majoring in psychology, to care for him and take him to his appointments.

Da’Nesha also occasionally ditched the wheelchair. Instead, she wrapped an arm around his waist so DaShawn could walk with her support.

“It wasn’t a hard decision,” Da’Nesha said about coming home. “I would do anything for my family. And then him, out of all people, he’s always been there for me.”

But while DaShawn could walk and talk, he still had trouble understanding what had happened to him.

“He’s constantly in the mirror, trying to figure out what happened to him,” LaDonna said. “I told him we’ll talk about it one day.”

LaDonna was looking ahead to the surgery at the end of June to return the portion of his skull that had been removed. For five months, his cranial bone had been stored in a freezer bank.

Two days before the operation, DaShawn asked LaDonna when the surgery was.

“I need to get my new brain because this one isn’t working right,” he told her. He wasn’t getting a new brain, LaDonna told him gently.

DaShawn occasionally called Vanessa, his son Deion’s mother, to see him. Vanessa would bring him over so DaShawn and Deion, now 2, could go to the park or play basketball in the cul-de-sac in front of their home in Auburn.

“When we were young, we were like, ‘we can’t wait to be dads’,” said Isiah Umipig, a best friend of DaShawn’s since the sixth grade. “We honestly just wanted to change our own history around,” he said, referring to the relationships they had with their fathers.

“He would sacrifice anything for Deion.”

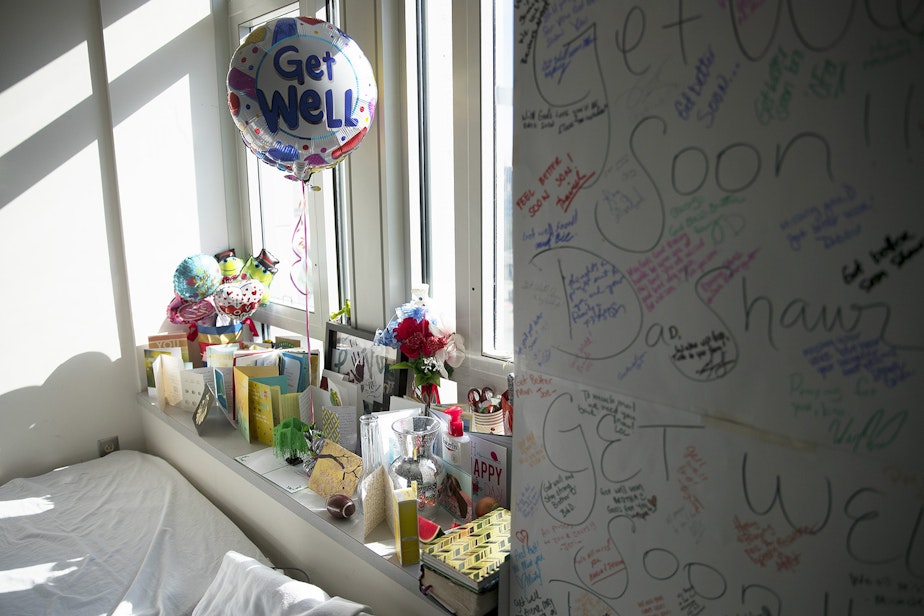

The night before Julian Tuimauga’s sentencing, DaShawn watched TV in his new bedroom. Hundreds of pictures and get well soon notes plastered the walls. His cane rested on the wall next to a Cardi B poster. A calendar on the wall had the date circled: November 15, 2018. LaDonna added a note in all caps: “TAKE YOUR TIME, DASHAWN.”

“What are you going to say in court tomorrow, DaShawn?” LaDonna asked.

“I didn’t do it,” he answered.

LaDonna, unsure if DaShawn meant this to be a joke, laughed. “No you didn’t do it,” she said. “What will you say to the young man that did do this to you?”

“I would ask him why he would do this,” DaShawn said.

Julian Tuimauga and prosecutors reached an agreement in August. In exchange for preventing federal prosecution, Tuimauga pleaded guilty to first-degree assault with a deadly weapon as well as malicious harassment, the state’s hate crime statute.

On the day of Tuimauga’s sentencing, family and friends filled courtroom 4F at the Maleng Regional Justice Center in Kent. DaShawn wore what he called his ‘churchfit,’ a black shirt, black pants, red tie and Chicago Bulls hat with a pair of diamond stud earrings.

It had been almost 10 months since the attack, but in the time DaShawn had spent recovering, he had never seen the video that Tuimauga had taken immediately after the beating. Prosecuting Attorney Stephen Herschkowitz didn’t think DaShawn should see the video, and arranged for him to be escorted out of the courtroom when it came time for the video to be played for the judge.

DaShawn objected at first. He wanted to see it so he could know what happened. LaDonna compromised with him; he could watch, but later.

Many of those who attended the sentencing wore visible expressions of shock on their faces as the video played. “I really wanted to scream,” LaDonna said.

Then, it was her turn to speak.

“On January 20, 2018, our lives changed,” LaDonna said, standing in the middle of the courtroom. “Not just DaShawn’s, but mine. The day that you made the cowardly decision to beat my son in the back of the head as well as his back and legs with a metal baseball bat, and left him there to die.”

“Why?” she asked. “Why? Why would you do this? You didn’t even know his name.”

She asked for justice for DaShawn, she told the judge.

“Love will always conquer over hate,” LaDonna continued. “That is why DaShawn is still here.”

Tuimauga looked down as she spoke.

“Julian snapped,” Robert Huff, Tuimauga’s defense attorney, told the judge. “He was not in control of himself.” Huff urged the court to consider the low end of the sentence range, given his client’s age — he had just turned 18 — and immaturity.

“They tell me he’s not a racist,” said Judge Julia Garratt of King County Superior Court, referring to letters that the Tuimauga family wrote to her. “They also outlined what a difficult life Mr. Tuimauga had when he was a youngster and living with his mother in Utah.”

Both the Tuimauga family and Huff, the defense attorney, had chalked up his use of the word “n———er” to youth culture, and the type of language used in rap songs.

“But words matter,” Judge Garratt said.

When Tuimauga addressed the court, he maintained that nearly beating DaShawn to death was not a hate crime.

“For all that know me, know I’m not a racist,” he said.

On the slur in the video: “I’ve been using it since elementary,” Tuimauga said. “It’s been used as a slang term, has been used by my friends of every race, my cousins, uncles, favorite music artists and favorite professional athletes.”

Judge Garratt said that she could empathize with the Tuimauga family in their grief over losing their son to incarceration.

“However,” she said, “I must balance that against the impact against Mr. Horne and the prison that he, through no fault of his own, has been locked in since January, and will be locked in for the foreseeable future, if not the remainder of his life.”

She sentenced Tuimauga to the maximum sentence, 13.3 years.

Smiling, LaDonna leaned over to DaShawn and whispered, “We won.”

Reporters and TV cameras swarmed LaDonna and DaShawn after the sentencing.

“DaShawn is still here,” LaDonna told the crowd.

“I’m still here,” DaShawn echoed.

Tuimauga’s stepmother approached the family, too, and apologized for her stepson’s crime. DaShawn extended his arm around her and hugged her. LaDonna wasn’t sure whether DaShawn knew who he was hugging, but she believed he did.

Leaving the courthouse, LaDonna screamed “Hallelujah” at the top of her lungs.

But she knew more challenges lay ahead.

“I feel like that battle’s over, but there’s still many more to fight,” she said.

After the sentencing, DaShawn continued with his new normal: traveling to Seattle for physical, occupational and speech therapy. His memories started to come back at a faster pace. He walked more; often without using his cane. He signed up for a gym membership.

On New Year’s Eve, DaShawn sat in a barber’s chair in Federal Way, watching the barber cut his hair for the first time since the attack.

In the mirror, he admired what he saw.

In the parking lot, LaDonna recorded a video of DaShawn on her cell phone. “New haircut, truth,” DaShawn said.

He took off his hat and turned in a circle to show it off. A faint scar was visible on the back of his head as he spun.

“I’m doing good,” he said, beaming. “You guys see that.”

Photojournalist Megan Farmer can be reached at mfarmer@kuow.org