A late paycheck and three days' notice: inside the threat of eviction

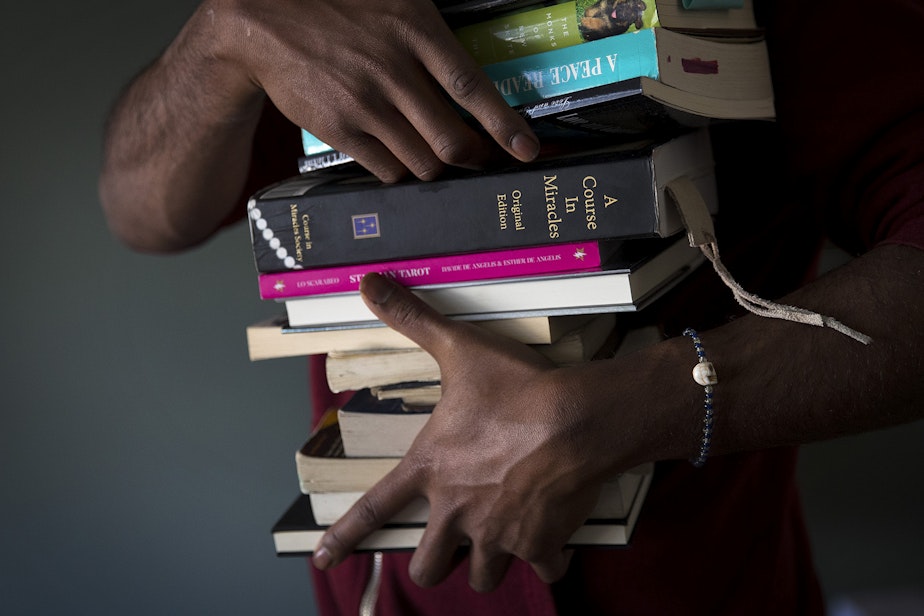

For Jordan, it all started with a late paycheck. In less than a month, he had to leave his apartment to avoid eviction.

Thousands of people face evictions in Washington state every year. Housing advocates say the process happens fast, disproportionately impacts people of color and can land people on the streets.

State lawmakers want to change eviction laws to help tackle one piece of the homelessness crisis. One of their goals is to extend the time tenants like Jordan get to catch up on rent.

We're not using Jordan's last name to protect his privacy.

J

Sponsored

ordan’s rent was due on February 1, and considered late after February 5.

Sponsored

His paycheck was being mailed and was delayed by snowstorms. By February 7, with no paycheck yet, Jordan hadn’t paid the $1,123 owed for the month for his low-income apartment in Seattle’s Pioneer Square and a three-day "pay or vacate" notice was posted.

His boss tried to pay online for him, something they’d been able to do in the past. But it didn’t work. The property management company said in a statement that payments made after the fifth of the month are considered late and must be paid via certified funds directly to the leasing office.

The three-day window closed and Jordan still hadn’t been able to pay. He also had nowhere else to go.

Sponsored

Not long after, he got a notice that his landlord planned to file an eviction case against him.

If the case was filed it would go on Jordan’s record. He said he couldn’t have that.

“My ultimate outcome is nothing on my record, because then I’m just, I’m done for,” he said.

So he chose to leave, to voluntarily vacate to prevent the case from being filed.

In less than a month Jordan went from being unable to pay rent to no longer having an apartment. And his case is not unique.

Sponsored

T

enants can face evictions for reasons other than rent. But a recent study by the King County Bar Association’s Housing Justice Project and the Seattle Women’s Commission found the vast majority of eviction filings in Seattle in 2017 were for nonpayment of rent. And of those, just over half were for one month or less.

Sponsored

Three quarters of tenants with evictions filed against them left their apartments.

Once the process is started, it can move quickly — and it can put people on the streets. Self-reported data collected during the county’s annual tally of the homeless shows eviction is one of the top three reported causes of homelessness in 2018.

The King County Sheriff’s office received more than 3,200 court ordered evictions in 2018, and had to physically evict 1,300 households. But that’s not a full count of how many people had to leave their homes due to the process.

Sponsored

By voluntarily vacating, Jordan joined an invisible group who face the cost of eviction without ever being counted in the statistics because their case is never officially filed with the courts.

S

everal bills that have been moving through the Washington State Legislature this session aim to reform the eviction process statewide.

Among them, extending the "pay or vacate" notice Jordan received from three days to 14 days, something he said could have helped him stay.

Edmund Witter, senior managing attorney for the Housing Justice Project, said giving people time to catch up on rent would make a big difference.

“I mean, we’re talking about the difference between when you’re getting a paycheck versus not,” he said.

Witter said the current system is unforgiving and doesn’t differentiate between tenants who are chronically late on their rent and may be bad actors, and those who owe small amounts.

Chris Benis, a landlord and an executive committee member of the Rental Housing Association said not all landlords are trying to chase people out of their properties.

“Every time you have a vacancy, you lose rent, sometimes weeks, sometimes months of rent,” Benis said.

He said many small landlords try to work with their tenants. But instead of putting the burden on them, he argues there needs to be a broader solution aimed at curing the issues that lead people to fall behind on rent.

“We need more subsidy programs, more community programs where a tenant who has a short-term problem paying their bills can get assistance and they can rapidly cure that default before it gets out of hand," he said.

Other opponents of the proposed changes have said they would hurt landlords who also have bills to pay, calling a 14-day pay or vacate notice extreme.

But after going through the process, Jordan wants people to know that it takes a toll.

He is now staying with a friend who also needed help to make rent for March.

“It can ruin peoples’ lives," Jordan said. "I am an instance of just pure luck."

This story has been updated.