In the absence of state law, Washington cities seek bans on public drug use

Dozens of cities in Washington state are considering new bans on possession or public use of illegal drugs. That’s after state legislators failed to reach an agreement on a new drug law in the final hours of the 2023 legislative session.

Seattle was part of the wave, with City Attorney Ann Davison announcing Thursday, “We are proposing legislation this week to discourage public use of drugs by making it a prosecutable crime.”

Some of these jurisdictions are seeking guidance from the city of Marysville, which has had its own anti-drug ordinance for months.

RELATED: Seattle leaders propose ban on public drug use, but others oppose the idea

Since the Washington Supreme Court struck down the state’s felony drug possession law in the “Blake” decision two years ago, the city of Marysville has passed two different ordinances to fill the gap. The first was a gross misdemeanor for drug possession, but that was later preempted by the state law making possession a misdemeanor and requiring multiple treatment referrals by police.

Last December the city made public drug use a misdemeanor. Marysville Police have made nearly 40 arrests under the new ordinance so far.

With the Legislature’s recent failure to enact a new statewide drug law, Mayor Jon Nehring said he’s been getting a lot of calls from other jurisdictions, to ask how Marysville's approach is working out. Nehring said it’s working well, but he thinks a state law would be a better solution to addiction.

Sponsored

“If there’s consistency across the state, it’s like, no, this is going to be prosecuted no matter where you’re at — Seattle, Marysville, Tacoma — then they’re more likely to accept the help, somewhere,” he said.

But Nehring and other mayors in Snohomish County opposed the final proposal that ultimately died in the Legislature, saying it didn’t go far enough. He said even if legislators can’t agree on how to penalize drug possession, they should still meet in a special session to pass the millions of dollars in funding that the bill contained for treatment services, and let cities determine their own penalties.

“They should still proceed with funding,” Nehring said. “There’s no reason to say you should have to swallow a bad bill to get the funding. We needed this before Blake.”

Nehring’s son Nate serves on the Snohomish County Council, where he also plans to introduce a countywide drug ordinance soon.

Across Washington, cities and counties are considering whether to make drug possession — or public drug use — a misdemeanor, or a gross misdemeanor. Misdemeanors can mean up to a $1,000 fine and 90 days in jail. Gross misdemeanors can receive up to 364 days in jail and a $5,000 fine.

Sponsored

“I think that a gross misdemeanor is probably the best path forward," Marysville Police Chief Erik Scairpon said. "It seems to be a good compromise. We’re taking something that was previously a felony and now trying to again put some kind of significant penalty behind it, with the idea of incentivizing treatment and rehabilitation.”

“My understanding is that our council is going to be workshopping our earlier possession ordinance and looking at re-implementing that with a July 1 effective date in the case of no policy pending from the state,” Scairpon added.

But Chief Scairpon said he also supported a provision in the state bill that allowed people to get their conviction vacated if they complete treatment.

“That’s something that I think can really, really help folks that are suffering from addiction," he said. "We don’t want somebody to have a criminal record necessarily. But what we don’t want them to do is to continue destructive behavior that goes beyond just affecting their lives but affecting the life of the community.”

Sergeant Michael Burtis, who administers the Marysville Municipal Jail, said up to 90% of the jail population typically has some type of substance use disorder, and jail staff routinely provide medication-assisted treatment to ease their symptoms.

Sponsored

“In many cases they have gone through the withdrawal process and are feeling better and doing well, so they’re in a good spot when they leave,” he said.

Officials say that’s a key moment when people can be more willing to enter treatment. If they are, Burtis said the jail refers them to a team that includes police and social workers, who attempt “to get them set up with housing, with treatment, even a ride to their treatment facility because they don’t have one.”

The state legislation would have mandated that people be given the option to engage in diversion and treatment instead of going to court. Marysville’s current ordinance doesn’t give people that choice. Instead, these teams work around the person’s criminal case or help them access treatment afterward.

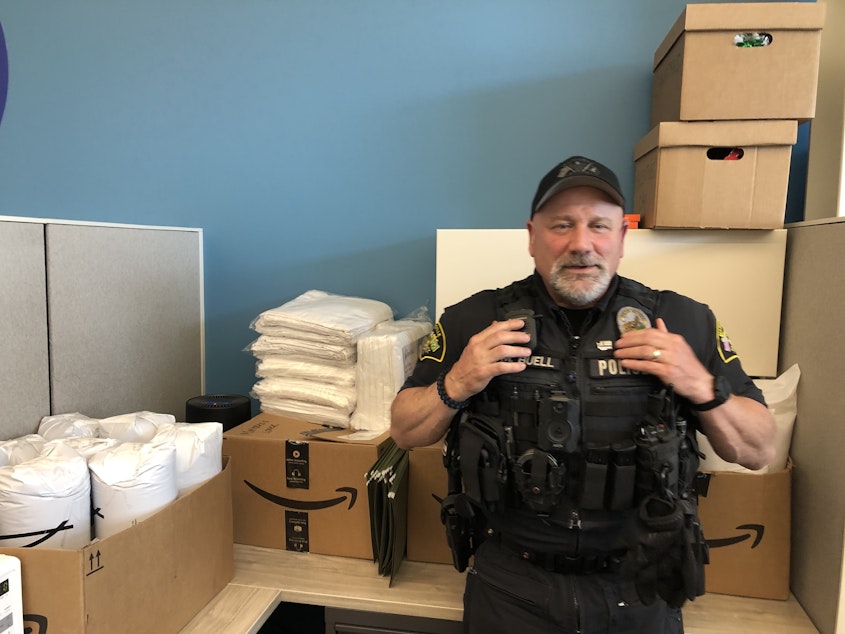

Mike Buell, one of the police officers on that team, does outreach in encampments and on the streets. He said his connection to the issue is a personal one.

Sponsored

“I’m also very interested in their stories. Because it hits close to home to me," Buell said. "I have a daughter who is a heroin addict. Or was. I’m sure it’s fentanyl now. But I wanted to dive deeper into it and talk to people that are actively using, that have an addiction, to make it make sense to me.”

So far this year, the city said the embedded social worker team has helped 10 people complete inpatient drug treatment and 13 people secure housing.

The prevalence of fentanyl-related overdoses is increasing the urgency on all sides.

As the coordinator for the recovery navigator program for Snohomish County Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, or “LEAD,” Morgan Webb helps clients access treatment services in neighboring jurisdictions to Marysville.

Webb said when people overdose on fentanyl it’s harder to revive them, and can require multiple doses of the reversal medication Narcan. She said the state proposal would have funded more Narcan and other treatment services. Meanwhile Webb said all the new city ordinances could make drug use less visible but more dangerous.

Sponsored

“When we push people further and further out, into the margins of society, further and further back into the woods, the danger of them overdosing increases," she said. "And so again, that’s why that Narcan component is so important.”

Backers of some of these new local drug laws said they are meant to push legislators to reach a compromise in a special session. Gov. Inslee has said he’s hopeful the state can still achieve a solution before the current state law expires July 1.

David Hyde contributed reporting for this story.