If these walls could talk, the stories they would tell

If this house could talk, what stories would it tell?

About the Irish-American couple that first owned it?

And the Japanese family sent to an internment camp?

Or the anarchists that played drums during the WTO protests?

We wanted to find a house in Seattle that would tell us about the growth of our city dating back more than a century.

We started with the 1940 Census, looking for Japanese families, because we wanted this house to tell the story of internment.

Sponsored

We sent letters to at least 100 homes. The small, yellow house at 1643 King Street replied. It probably wondered, “What took you so long?”

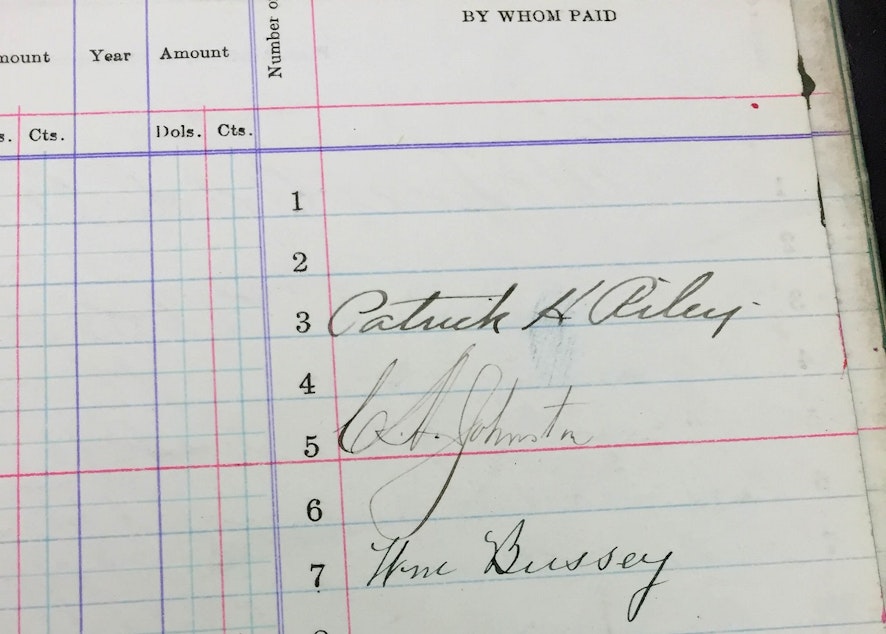

The King Street house sits at the edge of the International District and smells like warm bread, because Franz Bakery is one block up. In 1904, it was one of the first houses built on the block. Patrick and Nellie Riley were the first homeowners. They bought the new house for $1,050.

They owned it free and clear.

Your house has secrets. Here's how to find them

Sponsored

Patrick and Nellie had one daughter, Hazel, 9. She was their only child.

They were relative newcomers to the area. Patrick Riley was born in Kansas to Irish immigrants. We don't know much about Nellie because the 1890 Census records burned in a fire.

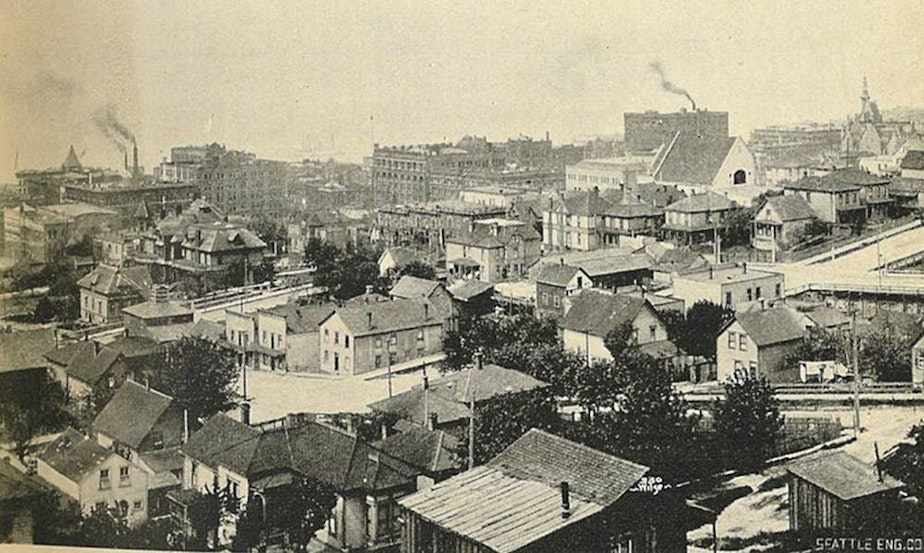

This was Seattle’s first big boom; people flooded in for the Gold Rush.

Patrick Riley likely also came looking for opportunity; he had been a prospector in Alaska, and also a cigar maker and barnman.

Sponsored

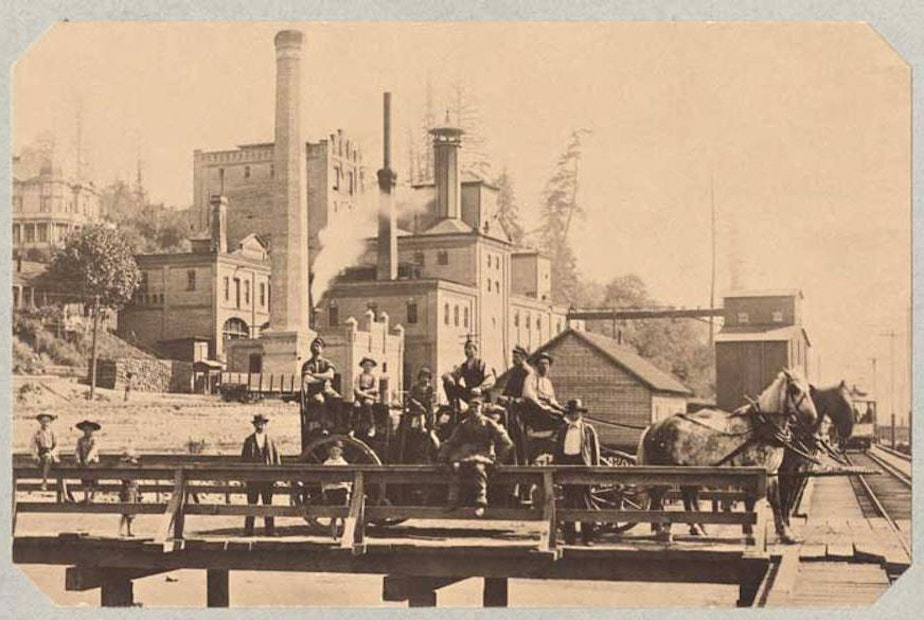

His last job was as a hostler at Seattle Brewing & Malting Co.

(Hostler = horse guy.)

(SB & M = makers of Rainier.)

Patrick Riley may be in the photo (above) of hostlers and beer guys, but we don’t know for sure. We like to think he was though, because he seemed to be someone who spoke his mind. He was the secretary of the United Brewery Workmen and had been noted in the newspaper for sticking up for his beliefs.

Sponsored

This was before Seattle became known for its passive, polite ways. This was frontier Seattle, known for corruption and schemes and bruising union clashes.

From their porch on King Street, the Rileys would have seen Seattle grow up.

The Smith Tower was built. The streetcar line expanded.

The city’s population tripled that decade.

Sponsored

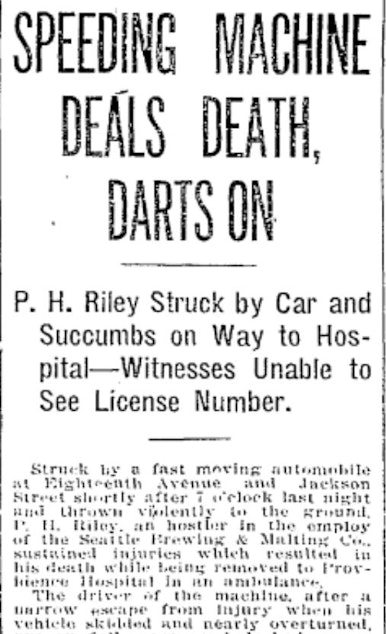

And people started driving cars. It was the car that killed Patrick Riley in 1915.

He was walking home from DeCaro’s market at 18th and Jackson when it hit him.

In later years, Hazel became a candy maker and married a man named Benjamin, who had been a tenant in the Riley home.

Nellie never remarried.

On the eve of World War II, the house on King Street was at the heart of a neighborhood called JapanTown. Where there had been English, Germans and Irish, there were now Japanese.

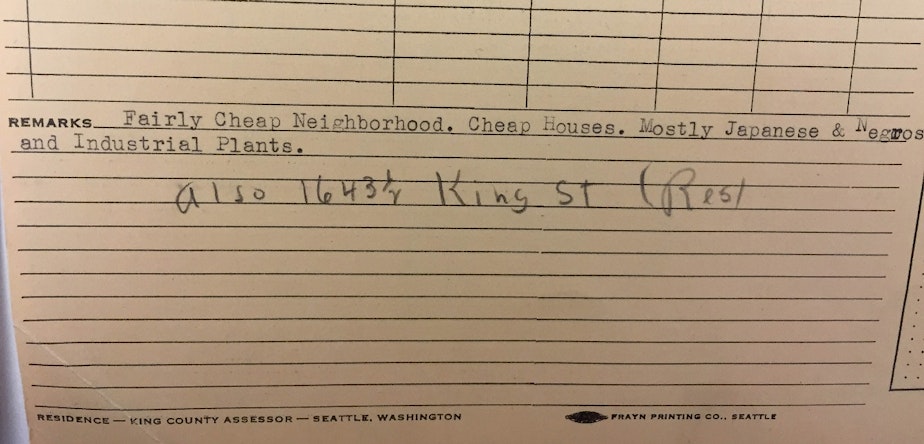

The King County Assessor described it as a "fairly cheap neighborhood. Cheap Houses. Mostly Japanese & Negros." (See below.)

In 1939, the Shojis moved in. Gennosuke, Kane and their four children.

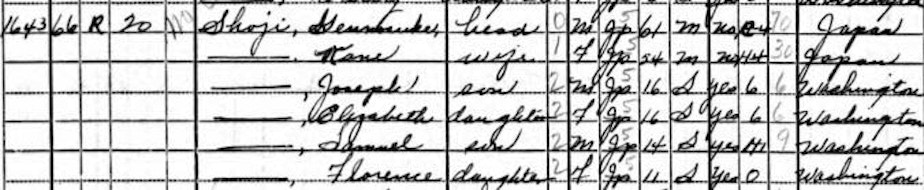

That’s them on the 1940 Census below. (Those six lines are what led us to this little framed cottage on King Street.)

And here they are posing for a photograph a few years before they moved into the King Street House.

Gennosuke Shoji was the pastor at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. Kane Shoji held a prestigious title in Japanese flower arrangement. They moved to the house around 1939.

The younger boy in the photo is Sam Shoji, who attended Garfield High School. He played the drums in the band.

You see the little girl seated next to Kane? That’s Florence.

Florence was disabled from an early childhood illness and paralyzed on one side of her body. She didn’t learn to sit up until she was 5 and would tug at people’s arms when she needed something.

This is their neighbor two doors down.

Winter 1941-42:

Dec. 7: The Japanese attack Pearl Harbor in Hawaii.

Feb. 19: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, allowing for the internment of Japanese and Japanese-Americans along the West Coast. The Shojis were sent to Minidoka in Idaho.

Now you see them.

Now you don’t.

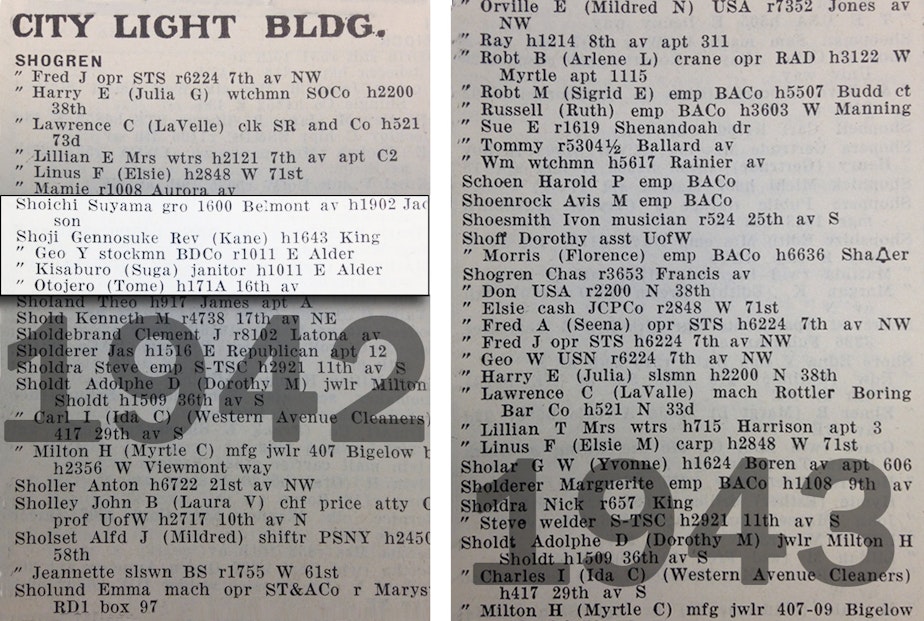

In 1942, the Seattle city directory lists the Shojis at 1643 King Street. But in 1943, the Shojis and other people with Japanese surnames have disappeared, whisked away to internment camps in the desert.

When the Shojis returned to Seattle, they moved into St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. They lived in what is now the gym.

They ultimately ended up in public housing.

Florence wasn’t with them though.

This is Sam Shoji. He was 16 when his family was sent to the internment camp.

This is him testifying to Congress decades about what happened to his family – and to Florence. “Before the war, they got her to a place where she could change herself, feed herself, and that all went away when they went to camp,” Sam Shoji said. (The video is 1 minute and worth a watch.)

The rest of his testimony is heartbreaking.

Many Japanese-Americans didn’t discuss internment later in life, but Sam Shoji made it his mission. He was a social worker and activist, and he was unrepentant in demanding an apology from the government.

He got it, too.

In 1976, President Gerald Ford proclaimed the internment was a national mistake.

After the Shojis were removed from Seattle, a Filipino family moved in.

Almanzor Guido was a union cannery worker. That’s him in back middle. According to Filipino records at the time, Guido enjoyed hosting parties at his home.

There’s a current that runs through this house, of people standing up for a cause.

The Rileys opened the door, as union leaders.

Sam Shoji pushed that door wide open.

The next few decades would raise the roof.

In 1972, a Filipino man bought the house. He was sympathetic to the United Farmworker movement and he rented the house to activists for cheap.

In 1999, anarchists lived in the house.

(Some called them “manarchists.” They would stand in the kitchen drinking beer and debating schools of anarchist thought.)

They paid $166.66 each. Taken together, that’s $1,000 minus four pennies.

They founded Books for Prisoners, Coalition of Anti-Racist Whites, Jewish Voice for Peace, and the list goes on.

That year, the house became a hub for the World Trade Organization protests.

The Indy Media Collective formed at the house.

Also, the Infernal Noise Brigade.

In the 2000s, the house shifted and became a known safe space for queer people and people of color.

They sang karaoke on a Magic Mic.

They had “sleaze parties,” which were hook-up parties.

And even though they were activists, they didn’t typically talk shop at home.

But like so many rental houses in Seattle, the King Street house was sold.

It had been a house for activists for at least 40 years.

“We literally woke up one day and there was a for-sale sign being pounded into the front yard,” Ronni Tartlet said. Ronni described herself as the house grandpa; she had lived there from 1999 to 2009.

“If we were not able to buy the house, this is just done,” she said.

They put together an offer, but it didn’t happen.

This is their farewell photo. We liked it so much we put it in twice.

Today, Kate and Aaron Zeichner rent the King Street house with their baby daughter Margo.

Kate Zeichner is a nurse-midwife.

Aaron Zeichner works at the Gates Foundation. They moved into the house three years ago. “We got married in this house. We had Margo in this house,” Kate Zeichner said.

The Zeichners generously opened their home to us, again and again.

The last time we were at their house, we told them what we had learned.

“Knowing all this history of people that have lived here before, it feels less ours but not in a bad way,” Kate Zeichner said.

Sometimes, when Kate Zeichner puts her daughter to bed, she thinks of the other children who have lived and spent time at the King Street house.

Hazel Riley.

Elizabeth, Joseph, Sam and Florence Shoji.

A baby named Nico from the activist years.

And now baby Margo.

Post-script: As we prepared to hit publish, we received an update from Aaron Zeichner. He told us his little family had just bought a house in West Seattle. And so a new chapter for the King Street house begins...

Sounds used in These Walls:

A lot of People Cutting Grass on a Sunday by Lullatone

Maple Leaf Rag by Scott Joplin

Sláinte-Butterfly Kid on the Mountain

1900 StreetSounds from Youtube courtesy of Mike Upchurch

Anvil by MrAuralization

Hammer by olliehahn12 (CC 0)

Streetcar by LG

Car Crash from Ella’s Archives on Youtube.

RainierBeer Ad from 1978. Property of Rainier Beer?

Sendo Kawaiya by Kikutaro Takahashi

Moonlight Serenade by Minidoka Swing Band

Newsflash Pearl Harbor-National Broadcasting Corp.

Japanese Internment Newsreel -EllaTV on Youtube

Black Cat, White Cat by Goran Bregovic

Goat Eyes by Infernal Noise Brigade

Just a gigolo Karaoke version

We Call This Home III by Alex Fitch

WTO sounds from Youtube and WTO Chant at 19:18

Lullatone: A lot of People Cutting Grass on a Sunday