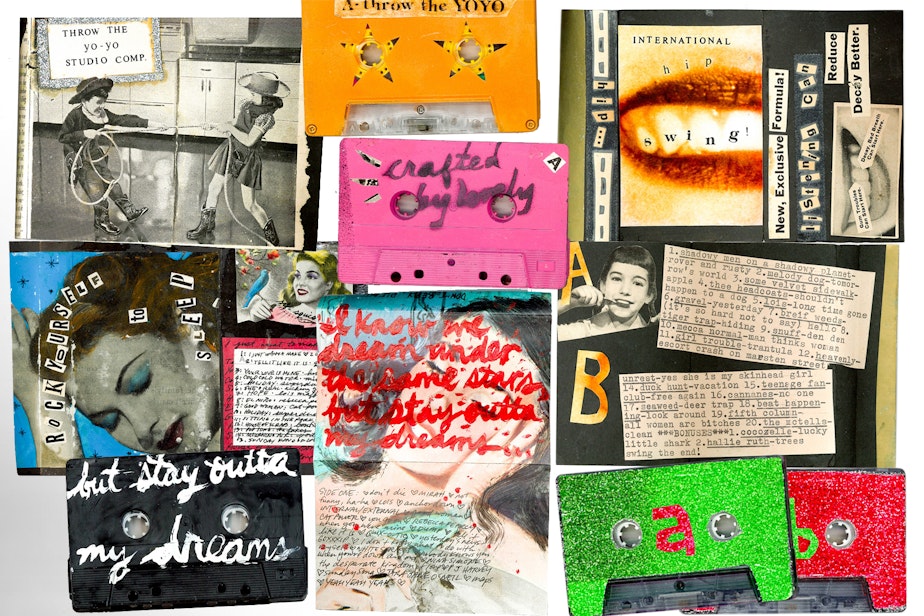

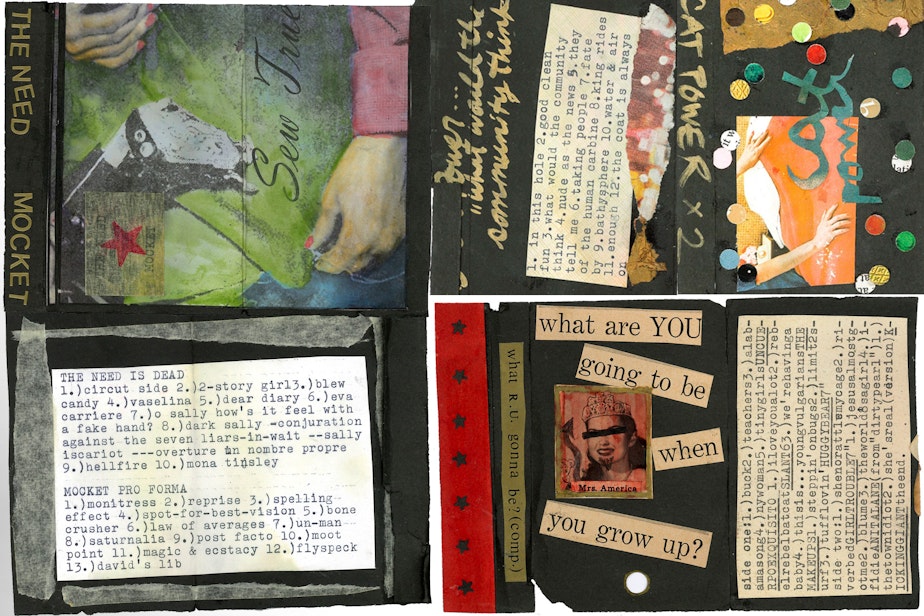

I was a queer punk kid who made mix tapes in the '90s. These were my creations

Lessons from a 1990s mix tape maker.

I’ve always loved the saddest songs. For show-and-tell in first grade, I brought my favorite Debbie Gibson cassette and made the class listen to all four minutes and twenty three seconds of my favorite song, “Foolish Beat” from Out of the Blue.

When it was over, I looked out at the class and was like, "Don't you feel anything?" Nobody seemed to be moved the way that I was moved by that song. It was there, standing in front of the whole class in that first grade classroom that I learned Lesson Number One: Music is Personal.

I grew up in Kenmore, which is about 25 minutes north of Seattle. My musical tastes evolved over time from Debbie Gibson and New Kids on the Block to oldies like Buddy Holly and Elvis and then back to chart-topping pop, hip hop, rap, and R&B.

As a tween, I would go the mall with my babysitting money and my best friend to buy cassingles from Camelot Music. I had a pretty sweet collection of cassingles in the early 90s. I made my very first mix tape in 1993 for my older sister Leslie from my cassingle collection. Listen to this mix on Spotify or below:

My parents sent me to a Catholic school in northeast Seattle to get a “good education.” Catholic school was stifling and somewhat damaging for me; a 5 year old with a sponge-like brain, I was repeatedly taught that I was inherently bad and must repent for my sins. As a budding queer kid, that repetitive message metabolized into a form of self hate that chases me to this day.

As I got older, teachers and administrators at the school became more punitive. When I started exhibiting a sense of style (as much as one can within the confines of a strict uniform policy), became a little bit more vocal, and started questioning authority, they weren't really happy about that. There were all sorts of rules that felt targeted at me. I felt like everyone wanted to control me and that grown-ups didn’t like who I was, as I was.

And I was like, “No thanks.” It just made me want to get louder.

Sponsored

Around 12, I had mostly phased out the chart-topping pop, hip hop, rap, and R&B for chart-topping alternative music. It was 1994, after all. Hole’s classic Live Through This came out exactly one week after Kurt Cobain killed himself.

I was super into Hole. I would listen to my Walkman at full blast, screaming along to “Violet” while my dad tried to listen to Rush Limbaugh on his way to drop me off at school. I fucking hated Rush Limbaugh. My dad would call me a feminazi, and I’d be like, “Dad, I’m 12.”

And then I heard riot grrrl music for the first time.

I was about 13 years old, and Leslie had moved to Olympia for college a few years prior. She’d become friends with a bunch of queer punks who were up to all sorts of good trouble. She had a friend who worked at Kill Rock Stars, a record label putting out punk music.

One Christmas, she brought back a handful of records: Heavens to Betsy’s Calculated, Bratmobile’s The Real Janelle and Bikini Kill’s first EP. I remember putting on Bikini Kill and being like, “Holy shit, there are people out there who are as pissed off as I am AND THEY’RE MAKING MUSIC ABOUT IT.” The politics of it, the community of it, the power of it was something that really, really spoke to me.

This began a years long deep dive into the underground music scenes across the U.S. and parts of Europe. I learned about K Records, Tobi Vail’s cassette label Bumpity, Chainsaw Records and so much more. It opened up a world of punk and queercore that helped shape who I am and through this music I learned Lesson Number Two: Music is Revolutionary.

My sister Leslie has always been the witness to my life. When I was in kindergarten, I’d lip-sync to Madonna on my My First Sony. Once I felt like I had my performance ready for an audience, I’d set up three chairs in the dining room: one for each of my parents, and one for Leslie. There would be two empty chairs, and Leslie would be there. My parents were just caught up doing whatever they were doing.

Growing up, most of my friends lived in Seattle city limits, so if I wanted to hang out with them, I had to rely on my parents to drive me there and/or spend an hour and a half on a bus. And walk. The closest bus stop from my house was three miles away. Isolation was a familiar feeling for me.

Around this time, both my parents decided that the music I was listening to was making me a Very Angry Girl. My mom threatened to throw away all my albums, so I’d sleep with my bed pushed against my door because I was afraid she was going to come in when I was sleeping and take my records. Music for me was a way out of a place that I really didn’t want to be. I had to protect it. Luckily, my parents’ threats proved empty.

As an angsty teenager trapped in the suburbs who wanted desperately to have control over my own life, I spent a lot of time in my bedroom making art and listening to music.

By then I refused to listen to bands that didn't have any women in them. Mostly I would listen to all-girl punk bands. I realized I didn't have to listen to men anymore because I discovered so many women putting music into the world. I could access that and that alone; I had that choice. That felt fucking cool.

My room was covered in photos I took of my friends and magazine cut-outs of my favorite musicians. It was my sanctuary, a portal to my future. This is where I made mix tapes on the regular. The music I listened to felt like a connection to a world that I wanted to be a part of. And I wanted to share it with people I loved.

I would spend a day dubbing a mix and making cover art for it and then I would mail it off or give it away. I would always have a specific person in mind while making these mixes. A lot of the mixes I made ended up going to my sister Leslie, because Lesson Number Three: Music is Connective.

The days of mix tape-making are largely over for me, but the ethos still lives on in the work I create. A visual artist with a passion for letterforms, text finds its way into my creations.

Whether it’s painting my nails and applying Letraset letters to every nail to spell out things like “Fancy Feast” and “Hard Core” or collaborating with my printer friend and owner of Bremelo Press, Lynda Sherman, words inspire most of my ideas. I love how the design of the type carries with it its own history and can help shape a narrative.

With letterpress specifically, there is something truly magical that happens when working with hand-set metal type. What you create with it is always a collaboration: you collaborate with your instruments and they collaborate with you. In this way, it’s like music.

Words will sometimes come from a conversation or a book or lyrics to a song, and I’ll send those words through my brain and see if I can make them into a new idea somehow. I go through this process with Lynda quite a lot.

Taking inspiration from the Dadaist movement, Lynda and I like to use the magic of anagrams to look for hidden messages within words or phrases that catch our attention. For example, “the risk is love” becomes “violets shriek” if you rearrange the letters. It’s like poetry: if you roll the words around a little bit, you’ll find new meaning.

I send mail to people all the time. I love this kind of connection. There aren’t very many surprises left in this age of instant information, so coming home to a special gift in your mailbox can be the thing that turns a shitty day into a good one.

We are social animals that need human contact IRL. We forget this because we are taught to forget this. We are more productive when we forget this. We are more profitable when we forget this. A letter in your mailbox is one small way I resist.

I am still very close to Leslie. She lives right down the street and we have dinner and go for walks and talk about life and help each other push ourselves into scary new territories that feel totally out of reach. I am so fortunate to have her in my life.

To say thank you to Leslie for all she has shared with me throughout my life, I have made her a mix tape, because Lesson Number Four: Music is Time Travel and Leslie and I have covered a lot of ground together. Listen to that mix below:

Special thanks to Kary Wayson for help with editing this essay.