How does choreography survive? Check out these diagrams

When a composer sits down to work, she might use a keyboard or a guitar to play the notes in her head. Ultimately, though, the permanent record of her song or symphony is a written score.

Same thing for theater and film. Written scripts provide official versions of the artwork.

But when it comes to dance, there is no single, standardized method for recording the confluence of movement and music.

Nevertheless, over the last century some American dancers and dance companies have used a system called Labanotation to create permanent records of their dances.

That's why this summer the University of Washington Dance Department invited Laban expert Leslie Rotman to record a 1947 duet called “The Pursued."

Traditionally, dances have been passed from person to person: A choreographer, or somebody who has performed the dance, teaches it to another generation.

You can think of it like a game of telephone, where a whispered message passes from one person to the next. The resulting message usually differs quite a bit from the original. The same thing often happens when a dance is transmitted from body to body. Memories can be fallible and change is often inevitable.

Rotman sat in on multiple rehearsals, notebook in hand, watching two people who had learned the duet from the choreographer to relay their knowledge to another generation of dancers.

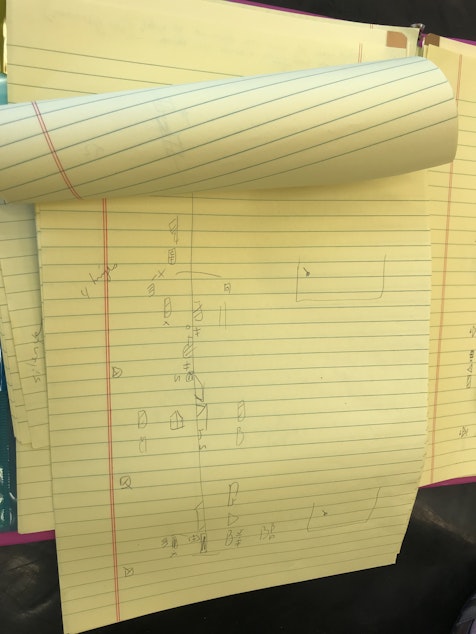

While the dancers worked together, Rotman paced the floor, jotting down drawings on yellow legal pads. Instead of sketching the dancers, Rotman was adding geometric symbols along two parallel lines.

Because dance is three dimensional, the symbols are used to represent space, direction, timing and where movement takes place on the body.

“The specific Labanotation I use to create a score is just that, very specific,” Rotman stresses. “If you follow and read every symbol, you will recreate the dance exactly as it was done.”

But Labanotation isn’t universally accepted.

Dance historians trace one of the first official dance notation systems to France’s King Louis XIV, in the 17th century. A more enduring system came out of Russia’s Imperial Ballet, in late 19th century St. Petersburg. A dancer named Vladimir Stepanov developed a way to correlate musical notes to anatomical movements. He and his colleagues used what is now called the Stepanov system to document many of the great ballets created there.

Seattle dance writer Sandra Kurtz says these records are the reason why so many of these ballets — ‘Swan Lake,’ ‘Sleeping Beauty,’ and ‘Giselle,’ to name just a few —are still part of the Western classical canon.

“When the Russian Revolution happened, several ballet masters wanted to leave the country,” Kurtz explains. “They took the notated scores with them, and that’s how they made a living, reconstructing the ballets from the scores.”

Pacific Northwest Ballet relied on those notated scores when the company remounted ‘Giselle’ in 2011.

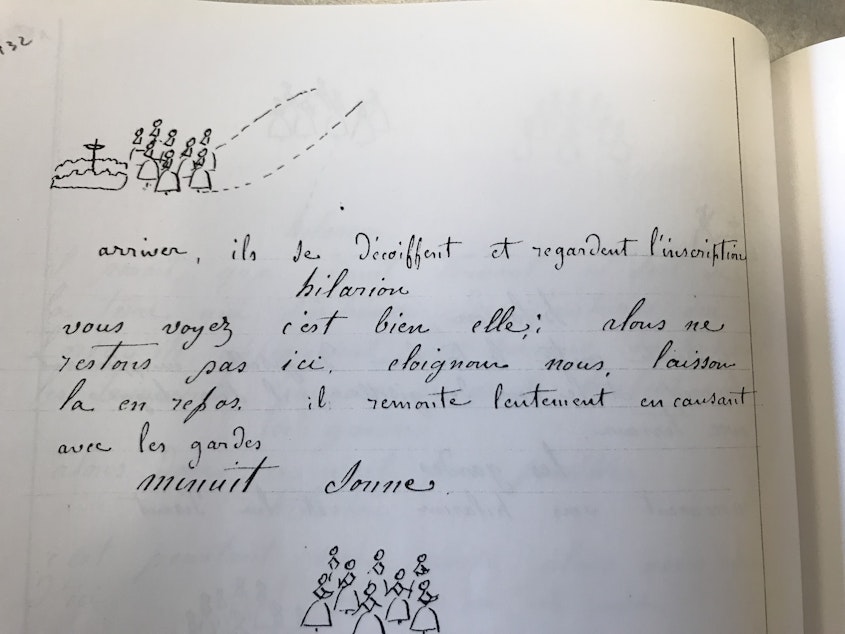

Dance historian Doug Fullington worked with PNB’s Artistic Director Peter Boal and scholar Marian Smith to reconstruct the ballet. Where there were gaps in the Russian notation, the trio turned to yet another notation system, devised by a Frenchman named Henri Justement.

Justement drew the dancers in motion, writing significant commentary next to his diagrams.

This supplemental material helped PNB figure out the characters’ dramatic impulses, and even revealed a comic scene that wasn’t captured by the Russian notation.

Although the Stepanov and Justement records were critical to reconstructing “Giselle,” Fullington says PNB doesn’t rely on a standardized method of recording and archiving new dances created at the ballet company.

“It may be because the systems in place are more time-consuming than people want to use,” he says. “So people get their own systems going on the fly, and they build them up over time.”

Notating a dance isn’t just time consuming: It’s also expensive.

The University of Washington Dance Department had to raise several thousand dollars to fund notation of the 10 minute duet. But advocates believe the investment is worth it.

Despite the widespread use of videos and photographs to document particular performances, they believe notation is a far more accurate record of a dance.

Dance writer Sandra Kurtz, who has taught Labanotation, says a dance score, in whatever system, becomes a permanent record of an artwork.

“It is a record of the thing itself. Not a variation, or a version of what we’re doing today. It’s the work itself.”