Four big housing ideas that could reshape greater Seattle: The Ripple Effect

The greater Seattle metro region is a hotbed of housing experimentation right now.

In many different cities, people are talking about new ideas, new approaches to this problem of how to build enough housing without tearing apart vulnerable communities in the process.

This is Part 3 of KUOW's series "The Ripple Effect," in which we cover how growth is pushing people away from the Seattle area and potential solutions to the problem.

In Part 1 of this web series, we explored how displacement pressure feels in one specific community. In Part 2, we chased ripples of displacement across the region. But regional problems require regional solutions.

This four-part series first aired as a special episode of KUOW's Soundside. You can click the "play" button to hear the whole one-hour documentary, or you can read the story in four abridged web stories here.

We're going on a road trip now, to visit four places where people are thinking outside the box. At each place, we’ll learn about a different strategy for growing as a region without pushing people out.

Our road trip begins in Seattle, the starting point of so many displacement stories.

1

Subsidize down payments on first homes

Sponsored

Rico Quirindongo was born in the Central District. His parents moved there to raise a family in a supportive community. But they moved away when he was a young child because they wanted him to attend different schools.

That displacement left a scar, and as soon as Quirindongo was old enough he came back.

“Coming back was hard because I feel like I missed the opportunity to grow up in a Black community in an urban core of a city,” he said.

Quirindongo made the Central District his study in graduate school. He walked every street in the neighborhood and learned about its institutions. Later, as an architect, he worked on notable buildings there, including the Northwest African American Museum. He moved into a home overlooking Martin Luther King Jr. Way South in the Rainier Valley.

Sponsored

Today, he has a position of influence as the head of Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development.

In that role, he’s supported the development of subsidized affordable housing, intended to help families at high displacement risk to stay in the neighborhoods they depend on. But he said there are not enough opportunities for people to buy affordable homes, and that keeps them from building generational wealth.

“One of the large issues that Black families in the [Central District] have, and BIPOC families have across the city, is that gap of access to capital," Quirindongo said. "How do we help families find the funding for that 20% down payment, which is not accessible to a lot of people.”

Quirindongo said he wants to see a program, maybe at the city, maybe at the state, that gives low-income and BIPOC families a bridge loan so they can purchase their first home.

2

Community Land Trusts to create more affordable homes for purchase

The second stop on our road trip is in Burien, where a small cottage development in a pleasant residential neighborhood is making its way through the permit process. The Ecothrive project will be a “community land trust,” which its leader, Denise Henriksen, said will protect its affordability forever.

The cottages are designed to be affordable for households earning less than $50,000 a year to purchase.

Here’s how a community land trust works:

Sponsored

It buys land, for the purpose of housing people. As a buyer, you purchase the home, while the trust keeps ownership of the land. You make payments on your home, building equity, as you would with a mortgage payment. You can take money out to improve the home or send a kid to college or something.

There’s a cap on how much you can sell it for. This guarantees that the person who buys it after you will also get an affordable home. You’ll get back your equity, plus a modest increase to cover stuff like inflation.

You won’t get rich by selling it, but it’s much better than a rental where all your money goes to a landlord and you’ll never see it again.

Community land trusts were first created by civil rights leaders in the deep South, “out of concern for the difficulties that African Americans were experiencing with land ownership,” Kathleen Hosfeld, executive director of the Seattle-based Homestead Community Land Trust, told KUOW’s Soundside.

Sponsored

RELATED: In Burien, and unusual affordable housing experiment gains steam

Today, the larger organizations that use this tool are starting to get more ambitious in the scale of their projects, and a growing number of grassroots organizations, such as the folks behind Ecothrive in Burien, are using the model to push their housing dreams forward, too. Henrikson said, “our goal is to not only build one, but build another one, and be at the position where we could help other communities build.”

3

Remove bans on “Missing middle housing” to create more homes on the same amount of land

Our third stop is in Renton, where Wanda Maldonado recently purchased a home from Habitat for Humanity.

You may be familiar with Habitat — they’ve been building affordable single family homes since the 1970s. But there’s something new they’re doing now that adds another solution to the mix: they’re building something called “missing middle housing.” We'll get to that in a minute.

Wanda Maldonado was already crowded with two teenaged daughters and a small dog named Jiffy in their two-bedroom apartment on Beacon Hill when their family added yet another member.

Hurricanes and an earthquake had left her father in Puerto Rico sick and isolated. Maldonado took him in.

“It was time, it was past time,” she said.

But where would she put him? She tried stuffing him into a shared room with daughters, who were already at each others’ throats, “fighting over clothes, and don’t touch this.” It didn’t work.

Thanks to Maldonado’s careful financial habits, she was pre-approved for a $400,000 home purchase. But she kept getting outbid on everything.

Luckily for her, Habitat for Humanity in King County had made a strategic change that allowed it to serve a lot more people. They decided to stop building single-family homes and focus exclusively on duplexes, triplexes, townhomes, row houses, and small condo buildings. That’s “missing middle housing,” the kind of housing serving middle-income families that’s been missing from the market.

Brett D’Antonio is the CEO of the local Habitat branch.

“It's really just about how can we have the greatest impact," D'Antonio said. "If we were to find and secure single-family lots, we'd only be able to help a handful of families a year.”

But by developing only in areas that have up-zoned to accommodate density, “whether it’s townhomes or stacked flat condos, we’re able to build 50 or more homes a year.” Maldonado said her four-bedroom row house has solved many of her problems, and that everyone now has their own rooms.

Habitat has started investing heavily in communities that allow missing middle housing options. In fact, it’s new zoning rules allowing things like backyard cottages that have drawn Habitat back to Seattle, where’s they’re now investing heavily after years of avoiding the city. They’ve been working on a South Park project that replaced a single-family home with 13 small homes, and recently completed another multifamily project in Lake City.

Back on the road

We’re headed to the city of Shoreline for the fourth and final stop on our road trip now.

The projects we’ve seen so far are small. Ecothrive in Burien will house 26 families. The Habitat project in Renton will eventually house 35 families. But the level of demand is far higher.

The Puget Sound Regional Council estimates the Seattle metro area needs 800,000 new homes by the year 2050. That means adding two times as many homes as there are in the city of Seattle right now.

All right, we’ve arrived in Shoreline. As we pull up, Mayor Keith Scully and State Rep. Cindy Ryu are there to meet us.

4

Give government the tools and money to create dense new communities

Right now, Shoreline is a city of mostly single-family homes. Mayor Scully said prices are rising so quickly though, that it’s slowly becoming an enclave for the rich.

The little ramblers and split-level homes from the late 20th century are selling, not to families, but to developers who rip them out and replace them with much bigger, much more expensive single-family homes. Denser development brings prices down a little bit, but there's no guarantee they'll be affordable either.

Below: Photo tour of Shoreline near light rail

The question Shoreline now faces is whether it can change in a way that protects people from displacement by offering them an affordable alternative.

Mayor Scully looked out over the crater of now-vacant land surrounding the future light rail station and described his vision for this area.

“It’s got to be walkable to everything, in order to really, really work," he said. "That means you walk to get your groceries, you walk to the library, there’s a pocket park very close by where you can walk with your kids and play, there’s community gathering places, there’s a place where you can exercise…”

But visions like this are hard to achieve.

That’s why Representative Ryu is supporting legislation to allow something called a “housing benefit district.” It would allow each city to divert some of its taxes that would have otherwise gone to Olympia, toward building up communities around light rail stations.

“Let’s say the Housing Benefit District legislation was available. And city of Shoreline had the tools — to be able to aggregate lots — to be able to put in the infrastructure,” Ryu said.

Any city with a light rail station or a bus rapid transit line could set up a housing benefit district. It’s not that different from how a whole city pools together resources to pay for a library, for example — something with collective benefits for the community.

To learn more about this idea and its potential, I turned to Faith Pettis and Rick Mohler, who have done a lot of work on this concept through their work with the organization Sound Communities.

Pettis is one of the people who helped design Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability Program, which rolled out in stages between 2017 and 2019 as it shook off lawsuits. The program requires developers to build or pay for some affordable housing, in exchange for density bonuses. That program was a big deal, but it wasn’t enough to erase the affordable housing shortage.

Pettis said this idea is much bigger.

“So we started this as a shoot for the moon idea," Pettis said. "If we could do anything we want to solve our affordable housing problem, what would we do. And let’s think big.”

Pettis said the way we do things now is backwards from the way we should be doing it. Right now, “around every light rail station, we get maybe one affordable housing project. And it just depends on where Sound Transit has an extra piece of property, or a developer who is committed to affordable housing may be able to secure a piece of property. We need to flip that on its head.”

Pettis said a Housing Benefit District would give cities (or other kinds of jurisdictions) the ability and funds to acquire land around transit before the land gets expensive.

“If we do that, the world’s our oyster,” she said.

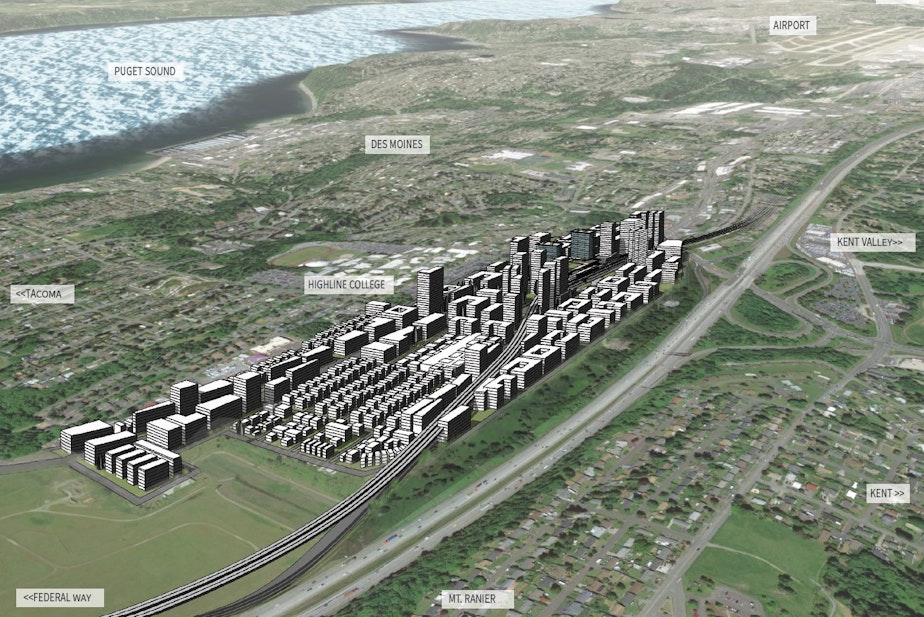

Rick Mohler is an Associate Professor at the University of Washington College of Built Environments. His students studied three light rail stations to determine how many homes a Housing Benefit District could realistically build there.

The number they came up with was surprisingly high.

“So if you just take, for example, 10,000 units and you multiply it by the 76 light rail stations that are either — have been built, under construction, or are being planned — that’s getting to the scale of housing production that we need to be thinking about over the next 20-30 years,” Mohler said.

This idea builds on some of the solutions we’ve already heard about. In some ways, it’s like a supercharged community land trust, but one powered by government. You could sprinkle in condos and missing middle housing to increase opportunities for home ownership. And additional financing, through a program like Rico Quirindongo told us about earlier, could help low- or middle-income families purchase those homes.

Other strategies we haven’t talked about could be layered in too. For example, we could streamline the permit process, so that housing gets built faster. Limited equity cooperatives are yet another option, one I hope to report on this spring.

Many of these ideas will end up in bills in the state Legislature this spring. Rep. Ryu said she’ll either sponsor a Housing Benefit District bill, or simply support one if a younger representative wants the honor.

Bringing these ideas home

I brought these stories back to my partner on this project, Bunthay Cheam, to hear how they sounded when compared to his lived experience. He loved the idea of a program that would subsidize a family’s down payment on a first home.

“I think that part is super important — to put capital into these communities, you know, like these communities that have a lot of pollution, a lot of noise pollution, have a freeway," Cheam said. "South Park has two freeways going through it, you know, it's undesirable until the wealthy folks need it. Right. And so now they're coming into these communities that were once undesirable.”

Cheam also noticed the similarities between the kinds of communities Housing Benefits Districts could create around light rail stations and the community he grew up in before South Park, Holly Park, now known as New Holly. Over many years, starting in the '90s, Seattle Housing Authority transformed its low-income communities into mixed-income communities, in part to cover rising costs and pay for new amenities like parks and community gathering places.

“I left before the change started happening,” Cheam said.

But his friends still live there, and tell him people at different income levels mostly keep to themselves. One of those friends described the situation to him like this: “The ones you could buy — like, market rate — were on the outer edges, kind of like near the green space. Whereas the denser ones were sort of packed in the middle. So like, by design, it was almost like this invisible border. Yeah, from everybody I’ve heard from, those who’ve stayed, it doesn’t necessarily translate into one community.”

So, there’s something for planners to keep in mind — mix all the housing up, so there’s less separation between communities.

But Cheam also touched on one of the missing pieces in all this.

How do we turn all this new housing, which is just a bunch of buildings, into a unified community? We’ll look at that in the final story in this series.

This story is part of KUOW's series, The Ripple Effect: How Seattle's housing woes push people out and what to do about it.

- The series was reported and written by Joshua McNichols, KUOW’s Growth and Development reporter.

- Freelance reporter Bunthay Cheam contributed to this report.

- Producers Sarah Leibovitz and Jason Burrows helped mix the audio documentary.

- Kamna Shaastri helped with community engagement.