The curious case of Latinos and Covid-19

Covid-19 cases are showing up among Latinos and people of color at higher rates across the United States.

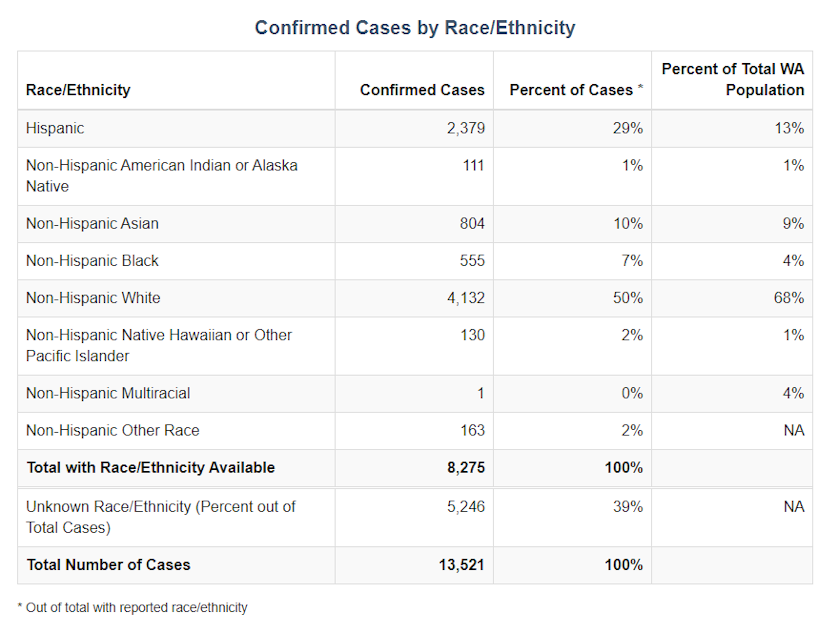

Initial data from the Washington State Department of Health shows Latinos account for nearly 30% of the cases, even though they make up a much smaller share of the state's population.

Here is what experts believe might be happening.

Wendy Lizette Martinez and her son wound up at the hospital on March 13. They had been with sick with the tell tale-symptoms of coronavirus: a high fever and dry cough.

Martinez’s son Mario has epilepsy, and Martinez knew that a fever could bring on a seizure, so they went to Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue.

By the following Monday, Mario, her 17-year old, had tested positive for Covid-19.

Doctors didn’t test her, but they told Martinez to assume she was positive too. She isolated in her home from her husband and four other children in their Renton home.

In Spanish, Martinez said she felt like she couldn’t get enough oxygen. She would start praying, ‘Please God, let me get through this,’ and there were moments where her fear rooted deeper -- would she get better?

Sponsored

“Se me iva el oxigeno y yo decía, ‘Dios mío, dios mío, ojalá pueda salir de esto, por favor.’ Y si hubo momentos donde ya hasta empece a sentir miedo.”

Sponsored

She felt sick with the virus for over a week and eventually went back to the hospital when she got worse. Doctors took X-rays that showed her lungs were damaged, put her on an IV drip to re-hydrate her, and sent her home.

Public health also conducted contact tracing, trying to prevent the spread to others around the family.

But Martinez doesn’t know how they picked up the virus. Was it through her nanny job? Or at her son’s school?

Sponsored

Martinez’s experience is similar to many people who got sick in the early days of coronavirus.

Still over time, the virus would take a heavier toll on communities of color in Seattle and across the state.

"W

e know this happens. We've seen this before,” says Dr. Leo Morales, co-director of the Latino Center for Health at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Sponsored

“Minority communities were disproportionately impacted by the last influenza epidemic, H1N1 in 2009,” he said.

Morales has been looking at data from the UW Virology lab from earlier this month. Two things stood out to him.

First, that Hispanic patients tested positive for the virus 16% of the time -- more than double the rate for white patients.

Morales noted that this data is for patients who were tested however; the actual number of people infected in the general population could be much higher.

Sponsored

The second thing he notes relates to people who received care in a language other than English.

The data showed patients tested positive at higher rates with languages like Khmer (38%), Spanish (35%), or Ahmaric (31%).

Compare that to English-only speaking patients who tested positive 7% of the time. Morales said there are a couple of possible explanations.

"One is people are only being tested once they're sick or much sicker when they test," he said. "The other possibility is that there's a much higher rate of infection in this subgroup of the population, which is obviously the most concerning possibility."

Other doctors in the Puget Sound area are seeing the same troubling trends.

Sponsored

Dr. Julian Perez works at the SeaMar White Center Medical Clinic, serving primarily low income and immigrant communities.

“I've talked with colleagues at other hospitals (like Swedish and Harborview),” he said. “They confirm that the majority of admissions in the last week are people of color.”

Perez has seen a similar pattern with SeaMar data and he has his own suspicions as to what’s behind the spike.

It could be that Latinos and other immigrant groups tend to live in multi-generational households. That means a lot of people, coming and going, as potential vectors of the virus.

Another thing is that Latinos are part of the essential workforce that can’t work from home. Numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that Latinos make up a good chunk of construction, agriculture, and the hospitality industry.

Morales had a similar thought: “You may have an occupation, like working in a meat packing plant, where you're working right next to other people. You may need to take public transit to get to work, you may not have the ability to isolate people who are sick, or it'd be very difficult within a home that's small -- all these factors may be contributing to the higher rate of infection among Latinos.”

Immigrants in general also tend to hold down more healthcare jobs potentially increasing their exposure to the virus.

Another key thing both doctors question is whether coronavirus information is readily reaching communities.

“It's one thing to have these forms and documents and websites that are translated. It's another thing that community members know where to find them, and are able to access them,” Morales said.

Dr. Perez said that’s partly why SeaMar owns and collaborates with Spanish radio stations like El Rey and Radio KDNA in central Washington.

“I do an hour each Wednesday and we're discussing Covid topics,” he said. “We're taking questions on the air. We're dispelling myths and false information.”

Perez said Latinos tend to listen to the radio in higher numbers, so he does his best to combat wrong information that people get from Facebook or Whatsapp.

SeaMar is also teaming up with UW and Yakima Valley Farmworkers Clinic, with the goal to further research the impact of coronavirus on Latino and immigrant populations.

B

ack with Martinez, the mother from Renton, she washes grapes for her kids to snack on. It’s been about a month since their coronavirus isolation.

She’s surprised to hear cases are higher for Latinos but also not -- some people in the community are stubborn, and others don't take the precautions seriously, she said. Some have no choice but to work to pay rent next month.

For her family, the virus has left its mark -- weaker lungs and an ugly, lingering fear.

“With my son, sometimes I’m like, ‘Hon, do you want to help me get groceries?’ she said. “He’s like, ‘No, I don’t want to go out there! I don’t want to risk getting sick anymore.’”

Neither she or her husband have been able to work all month. As time ticks on, Martinez knows financial troubles could get worse for her family and countless others.

As the pandemic ripples throughout the Northwest, data will trickle in and patterns will become clearer. But for Black and Latino communities, that pattern is a painful albeit familiar one, where the heaviest toll falls on their shoulders.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says the numbers so far show that the "a disproportionate burden of illness and death among racial and ethnic minority groups," citing racial residential segregation and the over-representation of Blacks and Latinos in jails, prisons, and detention centers.

And while the coronavirus did not bring these systematic disparities into existence, it has amplified them.