From Use Of Power To Mistrust In Government, 1968 Lessons Still Resonate

In 2018, NPR looked back on how events from 50 years ago — the pivotal year of 1968 — shaped our current world. In our "1968: How We Got Here" series, NPR's National Desk and reporters from across the newsroom examined more than 40 events, ideas and movements from that year and sought out to answer a simple question: How did each of those get us to where we are today?

The passage of time offered distance and nuance to the people and events that spurred cultural and political changes. At the same time, our look into the past often didn't reveal how much we've changed but rather how much those same struggles and challenges continue on our streets and even beyond our borders.

Here are five ways the events in 1968 still resonate today:

1. Use of American power abroad

Just as civil unrest, political divisions and war overseas challenged the country back then, questions over the use of American power domestically and abroad continue to this day.

Revisiting the My Lai Massacre, for example, presented an unforgettable view of wartime atrocities, military decisions and public opinion from the Vietnam War. In fact, NPR's Quil Lawrence found that history is taught to military personnel today as a lesson in the ethics of warfare. But another lesson learned by many is that there is often little accountability for those who perpetrate war crimes.

Lt. William Calley was the only American officer convicted for his role in the massacre that ended with the rape and slaughter of more than 500 civilians. Calley's sentence was reduced to house arrest by President Richard Nixon. He served 3 1/2 years.

John Sifton of Human Rights Watch researched war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan. He points to the Haditha massacre in Iraq in 2005. "In the end," Sifton said, "only one person was held accountable. And it wasn't a very serious punishment."

2. Mistrust of government

The Tet Offensive from earlier in 1968 proved that North Vietnam was far from defeated, even though the U.S. military and South Vietnamese forces prevailed. Before Tet, author Mark Bowden told NPR,

"You had the incredible rose-colored reports coming from Gen. William Westmoreland, who was the American commander in Vietnam. [He was] assuring the American people that the end was near, that the enemy was really only capable of small kinds of ambushes in the far reaches of the country."

But then came Tet, when North Vietnamese troops and their Viet Cong allies swept throughout cities and towns and into military bases, even breaching the walls of the U.S. Embassy grounds in Saigon.

Tet raised questions U.S. citizens still ask about whether they can trust the information coming from the government.

3. A nation divided

The assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy resonated as two key symbols of the fear and uncertainty from those times.

King's murder on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis in April 1968, unleashed many questions, sparked conspiracy theories, and revealed unfinished business begun and inspired by the leading voice against war and poverty and for civil rights.

For the generations born after him, the life of King has become a larger-than-life myth. Helping black striking sanitation workers in Memphis became his last living cause with "I AM A MAN" declared on sandwich boards during the daily protests.

Coretta Scott King spoke to crowds in Memphis four days after her husband was killed there. As NPR's Debbie Elliott wrote, her presence at the march "was the act of a civil rights leader in her own right." She finished the peaceful demonstration King had planned after violence and looting disrupted a previous Memphis march.

Journalist Barbara Reynolds co-authored Coretta Scott King's posthumous memoir My Love, My Life, My Legacy. A dozen years before King became a widow, the family home was bombed in Montgomery, Ala., during the bus boycott. Reynolds told Elliott that, in response to her father-in-law's urging to leave Alabama for safety in Atlanta, Mrs. King was firm:

"She said to him, 'You don't understand, Dr. King. I'm married to Martin, but I'm also married to the movement.'"

NPR Music looked at what was on the radio the week King was killed. It was the late Otis Redding's single "Sittin' On the Dock of the Bay," perched above names like Aretha Franklin and rising stars to come. In fact, the song almost wasn't released.

NPR's Eric Westervelt reported on how the legacy of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles was memorialized by the construction of six high schools on or near the site of his assassination.

"In the spirit of RFK, they took on big real estate developers, including one named Donald J. Trump, and took a stand for underserved neighborhoods. The very spot Senator Kennedy lay bleeding, cradled by a teenage busboy named Juan Romero, is now a center for teaching and learning."

4. Women's lib

The so-called "women's liberation movement" began to take off in the late '60s, especially with a demonstration at the Miss America pageant in 1968. We touched on the rise of women in politics with the story of Shirley Chisholm , the first black female elected to Congress. Her win still resonates with today's election cycle — 2018 was nicknamed the "Year of the Woman," resulting in a record 127 women taking seats in the House and Senate this week.

"Harper Valley PTA" and Jeannie C. Riley had a moment in 1968. Riley became the first woman to reach the top of the pop and country music charts. But as NPR's Elizabeth Blair learned from Riley, the record industry wanted to promote her, "not a person, [but as] a sassy sexpot instead of a singer." It's worth noting that Rolling Stone recently chose Harper Valley PTA among the "Greatest Country Songs of All Time."

5. Protesting in the streets and on the podium

NPR's Carrie Kahn reported that the student movements in France and the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia inspired the 1968 student protests in Mexico. The violence between protesters and police came only weeks before the start of the Mexico City Olympics, Kahn recalled.

"The death toll was officially 25, though it's been estimated that as many as 300 died, in an action which, was not recognized as a state crime by officials in Mexico until earlier this year [2018]."

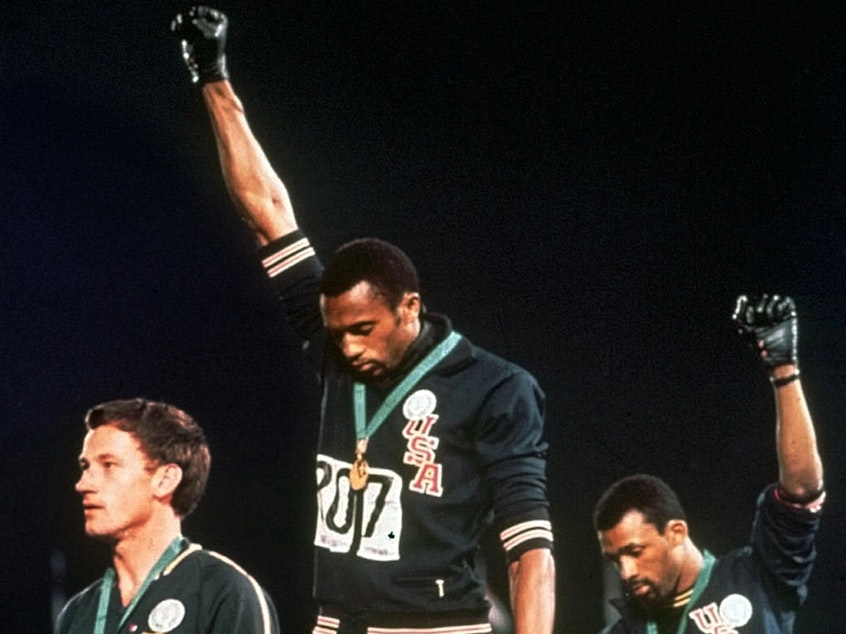

At those Mexico City Olympics, two U.S. athletes, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, staged their own protest — raising fists on the podium after winning medals in track.

NPR's Karen Grigsby Bates reports that Carlos met with Martin Luther King Jr. before the Olympics. He encouraged the black athlete to do something to call attention to the plight of black Americans.

A nonviolent protest while all eyes were on Mexico City, King said, could cause concentric ripples, like tossing a rock in a pond.

In an oral history for the Library of Congress, Carlos recalls that King's words carried him over into Mexico City. "I wanted to do something so powerful that it would reach the ends of the earth," Carlos said, "and yet still be nonviolent."

That long-forgotten protest in 1968 inevitably evokes comparison to the controversy today surrounding kneeling during the national anthem by NFL players, notably Colin Kaepernick. [Copyright 2019 NPR]