Fatal police encounters in Washington fall to 5-year low

In the wake of 2020's protests against police violence, Washington state passed a series of new police reform laws. They restrict how and when police can use force, and expand the penalties they can face for misconduct.

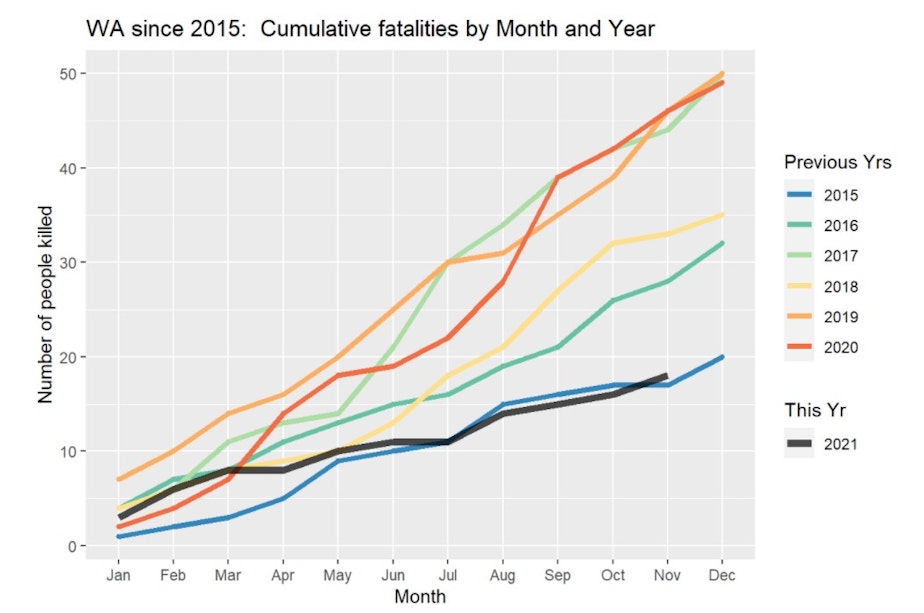

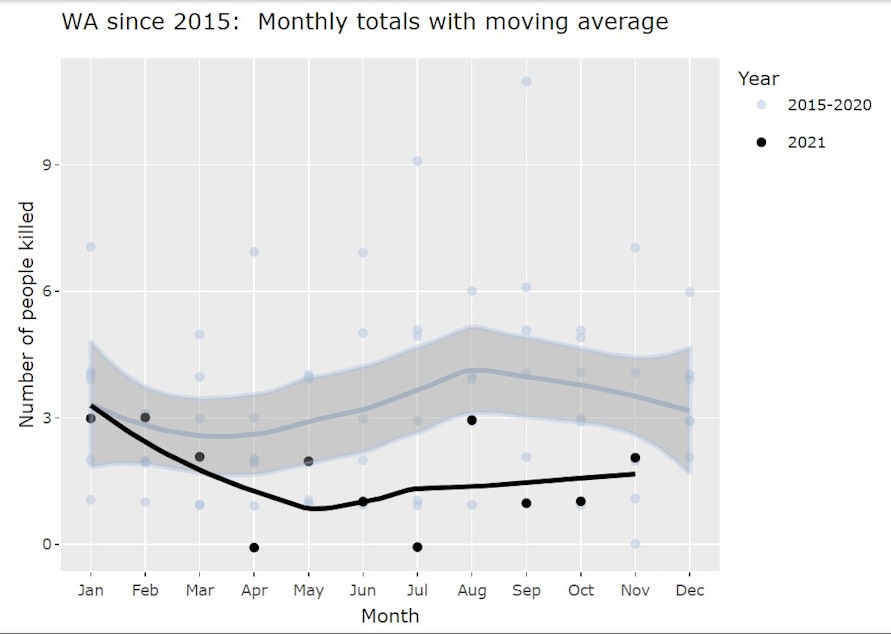

Now there’s intriguing new data about police interactions in Washington state. The number of people who died in police encounters in the first 11 months of 2021 declined more than 60% from the year before.

In the last decade, the number of people who died during encounters with police had been climbing faster than the rate of population growth. This year, that trajectory appears to have changed.

Leslie Cushman is with the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, which held a press conference December 9.

“As of today there are 18 deaths this year compared to 46 this time last year. That’s big news,” she said.

Police reform advocates started to notice the decline in fatal police encounters last spring. Martina Morris is a retired statistics professor with the University of Washington. She has used data compiled by the Fatal Encounters Project and other sources to analyze deadly police encounters in Washington on behalf of the advocacy group Next Steps Washington.

Morris said the absence of any fatal police encounters in April and July this year got her attention.

Sponsored

“When we hit those ‘zero months' — and we hadn’t had a zero month since 2015 — I started telling people, ‘I think I’m seeing something in the data,’” Morris said. “So people have been very excited about this, I think also cautiously optimistic.”

Morris said the decline doesn’t coincide with the pandemic, because 2020 still saw an increase in fatal encounters. And she notes that other states are not showing similar reductions. But she said she'd like to see five more years of data to feel more certain.

Nevertheless, reform advocates say this is the type of outcome they’ve been seeking over the past three years. That’s when voters passed I-940, the initiative that made it easier to charge officers with negligence in their use of deadly force. It later became the Law Enforcement Training and Community Safety Act (LETCSA).

Under Washington's new law, police officers have been criminally charged in the deaths of Jesse Sarey in King County and Manuel Ellis in Pierce County. Sonia Joseph, whose son Giovonn Joseph-McDade was killed by Kent police officers in 2017, said, “I think it’s a wake-up call that officers just cannot operate above the law and be lawless.”

Sponsored

Reform advocates like Joseph, who now serves on the state’s Criminal Justice Training Commission, believe those prosecutions, combined with this year's series of new laws including expanded ability to decertify police, are driving the decline in fatal police encounters.

But there is another way to interpret these new numbers. Some analysts say it may reflect the fact that police are interacting less with the public overall.

“The use of force is generally tied to arrest activity,” said Matt Hickman, a criminal justice professor at Seattle University. “And we know that arrests are generally down also during this timeframe. So it may be correlated with reductions in police activity.”

Eric Drever is chief of police for the city of Tukwila. He said that interpretation resonates for him.

“We have officers in Washington state that are concerned about engaging,” he said, adding improved outcomes will be driven more by training, while this may be a result of confusion.

Sponsored

Drever said since all the new legislation took effect last July, his officers still wrestle with questions about what the laws allow them to do.

“With that comes hesitation which, that’s not good for the officer, it’s not good for the community. That becomes doubt and questioning whether they should or shouldn’t engage.”

Drever co-chairs the committee that is helping launch statewide independent investigations of police deadly force. He said he supports the intent of the new laws, but not all of the new restrictions.

“This reform, it is working,” he said. “It’s just not as clean as it needs to be, in order to best serve our communities.”

Police reform advocates worry that police don't like these new laws, and are using them in some cases as an excuse not to respond.

Sponsored

Nickeia Hunter became active on police accountability after her brother Carlos Hunter was killed by Vancouver police in 2019. She said she doesn’t want police to disengage, but she does want them to pause and de-escalate whenever possible.

“I do not ever believe that the police need to be abolished or wiped away or anything like that, that’s never, ever been my goal,” she said. “The police need to be strengthened, they need to be reminded of their duties, and they need to be properly trained.”

Legislators who helped pass the new policing laws say they are prepared to work on a few clarifications next year, but they also want to defend the laws from being rolled back. They said the decline in fatal police encounters will be an important piece of the conversation.

State Representative Jesse Johnson helped pass the reform bills, and said the new legislation has generated what he called an “expected freak out” among opponents.

“Whenever you do something that’s robust, systemic change, you’re going to have 'the freak out' by those folks in the institution who want to keep the status quo," Rep. Johnson said.

Sponsored

But Johnson said he is willing to look at changes to the new laws around detaining suspects. The new law requires police to have more evidence before detaining someone after a crime is reported.

“I do think that with gun violence situations, more the potentially murderous, serious situations we have to look at that and engage in a conversation on what that means,” Johnson said.

Tukwila Police Chief Drever said he supported the old standard of “reasonable suspicion” to justify detaining someone, rather than the new standard of “probable cause," and he hopes legislators will reach some kind of compromise.

“I don’t know exactly what that is aside from taking a closer look at how we can try to meet the intent of those who wanted this change, and find ways to make it work so criminals aren’t getting away,” he said.

Marco Monteblanco is the president of the state’s Fraternal Order of Police, which gave feedback on and supported many of the new laws. He said he’s not prepared to draw any conclusions from the initial fatal encounters data.

"The bottom line is that it’s really too early to tell how well the new measures are working," Monteblanco recently wrote. "What’s most important, in my view and in the view of our organization, is that legislators, law enforcement, and the broader community maintain strong lines of honest communication on these issues and continue doing the hard work to rebuild the mutual trust and respect between law enforcement and the broader community.”

Matt Hickman at Seattle University also said he thinks it's premature to draw conclusions based on this year's data on fatal police encounters. But he is optimistic that a new use of force database in the works in Washington will bring answers on which policies and trainings are effective.

"It’s a massive undertaking but I am very optimistic about it. I think that our state Legislature did a great job with this bill," he said. "I think that Washington state is going to lead the nation.”

The database will be available to the public, and it will reflect not just fatal encounters but injuries and other interactions.

Editor’s note 12/16/2021:

The Fatal Encounters Project lists eight additional “fatal encounters” involving law enforcement in Washington State so far in 2021 that have been excluded from Morris’ charts. These incidents concern people who died by suicide in the course of police encounters.

Bob Scales, CEO of Police Strategies, disagreed with Morris’ analysis and KUOW’s report. “If you’re going to look at the impacts of I-940, those types of incidents should be included in the analysis,” he said. Scales noted that there are no official U.S. numbers on fatal encounters with police.

Morris, the researcher, said there are valid reasons to track suicides involving law enforcement: the narratives may change as more information becomes available, and the cases also raise questions about whether a different type of response might have changed the outcome.

“Both of these are good reasons to have the data available in Fatal Encounters, and I’m glad that they are there, but I exclude them from my reports because technically these people were not killed by police and that’s what my reports focus on,” she said.

Morris said her analysis includes three shootings recorded in October and November by The Washington Post, which has updated its data more recently than Fatal Encounters.