Fatal gun violence looks different for Seattle kids, depending on where they live

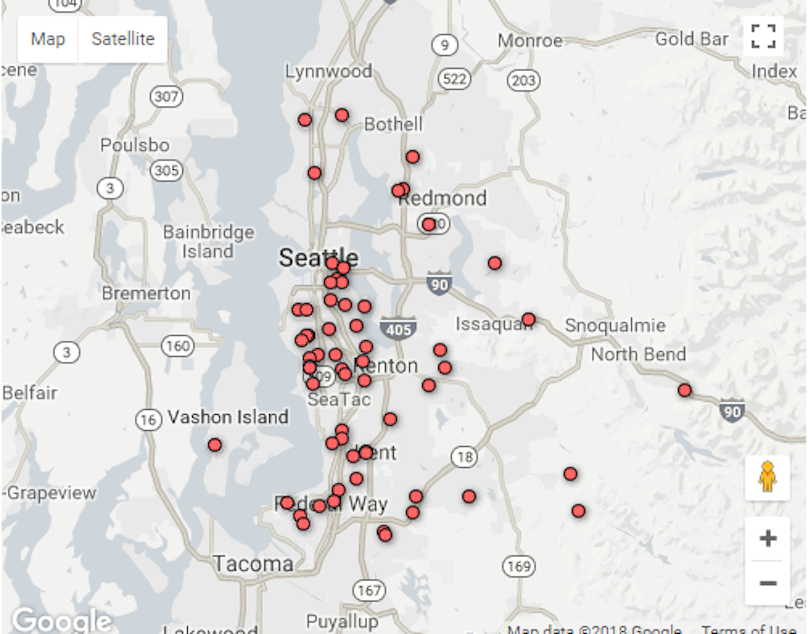

Look at the map above. What do you notice?

Each red dot represents someone 18 or younger who died of a gunshot wound in King County in the last nine years.

Sixty-four kids total.

In Seattle, all of these dots—minus three—show gun fatalities that occurred south of the Ship Canal.

The deaths follow existing geographical demarcations that have historically separated north from south, white from brown, high incomes from lower ones.

We created this map on a hunch after requesting nearly a decade of data from the King County Medical Examiner. We wanted to look at local gun deaths in light of the national conversation on shootings and grade-school kids.

Of the 64 kids who died, 36 were homicides, 24 were suicides, three were undetermined, and one was a fetus killed when her mother was shot.

The experts we spoke to weren't surprised by the geographical disparities and the number of suicides.

"The general public is not well aware of the true demographic, the true nature of the victims, and the fact that 70 to 80 percent of firearm deaths are firearm suicides," said Tony Gomez, violence and injury prevention manager for Public Health Seattle-King County.

(Gomez was referring to all gun deaths; 38 percent of the youth we examined died of suicide.)

Gomez noted that gun violence, like many public health issues, tends to follow similar patterns of disparity in south Seattle and south King County.

"There is a contagion element to violence in general, and historical trauma—we don't know to what extent—but it does exacerbate what's going on there," Gomez said.

Sean Goode, a native of south King County and the executive director of Choose 180, a nonprofit that provides case management for at-risk youth, said he sees this kind of trauma firsthand in the communities where he works.

"Violence is a disease," he said. "And when you have a community that's sick with the disease of violence, and it goes untreated, it continues to permeate. We quarantine people who are perpetrators of it, and we don't really provide the necessary services to get them healthy."

We don’t include race on this map for two reasons: We have just three years of information, from 2015 to 2018, and the data is unclear.

We know that:

Nine of the youths were black.

Three of the youths were of Asian descent.

But less clear is how many were white or Latino. Sixteen kids were listed as white, but we believe that nine of them were Latino, based on Spanish last names and information gleaned from obituaries online. For example, one boy listed as “white” was born in Mexico and had a Spanish first and last name.

If this is true, then 75 percent of those who died of firearm injuries were kids of color.

The community impact of gun violence can be long lasting, Goode said. But too often, he said, the community doesn't receive the resources it needs to heal. Gentrification and displacement are making that even more difficult, he added.

"Seattle is benefiting from all the tax dollars coming from companies like Amazon," Goode said. "But then these communities move to south county, in like Auburn or Des Moines or Kent, and they don't have the social service infrastructure or dollars to create meaningful solutions."

King County has only recently started collecting gun violence data from local law enforcement based on where they receive reports of "shots fired." An initial report found that 240 people were killed or wounded by guns in King County last year. Of them, 67 percent of the homicide victims and 54 percent of the injury reports came from outside of Seattle.

The report also found that about half of the victims were younger than 25; 83 percent were people of color.

The prosecutor's office doesn't collect data on suicides, nor does it collect data on police shootings. It's been historically difficult to research gun violence, said Dr. Fred Rivara, a professor of pediatrics and violence researcher, because of a 1996 amendment that restricted funding to the Centers for Disease Control for studies that could be used to advocate for gun control.

The Dickey amendment, both Rivara and Gomez agree, has chilled research on guns.

"We don't really have money to do much in the way of gun research," Rivara said. "It's impacted our ability to do projects."

This lack of information is why we requested detailed reports from the medical examiner. We found that relying on news stories and government reports provided a too-hazy snapshot of the problem. In fact, many of the kids who died weren’t mentioned online at all.

Rivara noted, too, that in media coverage of gun violence and youth, discussion of youth suicide is often missing.

"The thing you have to realize is those mass shootings, even altogether, add up to a minority of gun deaths in the U.S.," Rivara said.

This map is the beginning of our research into youth gun deaths in King County. What do you want to know? Is there a story we should know, or someone you’d like to commemorate? Write to us sydney@kuow.org and iraftery@kuow.org.